There’s a word I’d like to strike from business jargon: aspirational. It’s a dreadful neologism, about as bad as incentivize, and only slightly better than incent. But more to the point: I’d like to kill it because it’s on the verge of irrelevance.

As typically defined, a brand is “aspirational” when everyone wants it but only a fraction of that group can afford it. You’d think that definition would apply to any luxury brand, from Bugatti to Patek Philippe. But key to “aspirational” is also a hint, however faint, of attainability. Few of us working stiffs imagine we’ll be driving $2.5 million sports cars or rocking $50,000 timepieces. But we might lease a BMW 3 series or flash a midrange Cartier. We don’t picture ourselves sipping $2,000 Château Lafite Rothschild by the goblet on the decks of our yachts. But every now and then, we’ll splurge on a $200 bottle of Johnnie Walker Blue.*

Aspirational brands rely on a high-low strategy. They price their main lines high for the hedge-fund crowd. But they hedge low on their entry-level diffusion lines, priced to capture the aspirational majority. Aspirants dream about Birkin bags, but they’ll settle for anything with an Hermès logo on it. So Hermès sells Birkins to wealthy socialites, and not-quite-Birkins to those who’ve seen them on TV. In doing so, it captures all the marketplace demand for its brand name through price discrimination. Some luxury brands eschew aspirational customers altogether—you won’t find a Tom Ford suit for less than a couple grand. Others have forged empires out of them—you can’t afford Ralph Lauren’s Purple Label, but you’ll love the Blue.

High-end prices have gone off the deep end; as the Wall Street Journal reported, “in the past five years, the price of a Chanel quilted handbag has increased 70 percent to $4,900. Cartier’s Trinity gold bracelet now sells for $16,300, 48 percent more than in 2009. And the price of Piaget’s ultrathin Altiplano watch is now $19,000, up $6,000 from 2011.” But while spending on luxury goods is still growing, the growth is slowing down. Luxury consumption was an impressive $390 billion in 2013, a 7 percent increase over 2012—but a drop from the previous year’s 11 percent growth rate, with a projected rate of only 6 percent next year. Time attributes the slowdown to a cooling market in China, where President Xi Jinping recently initiated a crackdown on bribery and corruption (those had been major drivers of luxury purchases, especially among government officials).

The Wall Street Journal suspects that America’s high-end consumers are simply fed up with double-digit, year-over-year price hikes. The Journal shows us a heartbreaking case of sticker shock:

Connie Oclassen of Mill Valley, Calif., said she couldn’t buy as many pairs of Jimmy Choo flats as she used to, since prices climbed from $650 a pair from $495. In the past she would buy four or five pair a year. This year, the retired marketing executive will limit herself to three.

Pity the plight of poor Ms. Oclassen, whose $1,950 Jimmy Choo budget will have to see her through a 365-day stretch. But she’s the canary in the diamond mine. A retired marketing executive with a luxury shoe budget is probably better off than most of us, but she’s probably not rich by the standards of today’s global elites. She’s the definition of an aspirational customer: upper-middle class, using semi-approachable luxury brands to sample the gilded lifestyle.

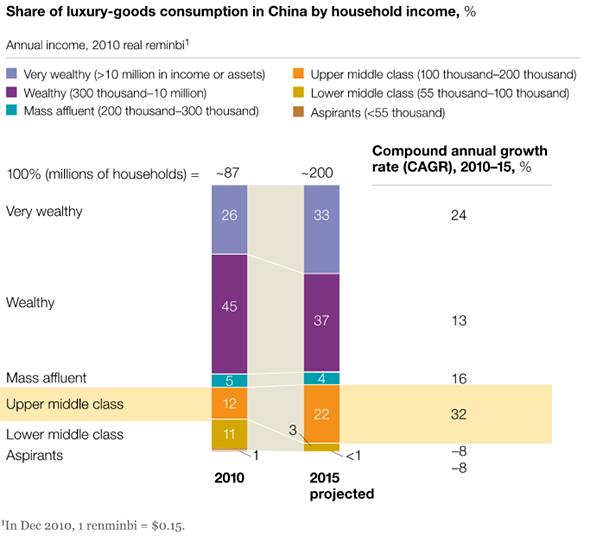

China will account for 20 percent of the global luxury market in 2015, but it’s feeling the squeeze around the middle, too. McKinsey suggests that China’s share of luxury-goods consumption is trending more and more heavily toward two segments: its “very wealthy” and its “upper middle class.”

Source: “Tapping China’s luxury-goods market,” McKinsey & Co., April 2011

We should note that “wealthy,” in McKinsey’s designation, means an annual income starting at 300,000 renminbi, or approximately $48,000. “Mass affluent” means an income in the range of $32,000 to $48,000. China’s “upper middle class” earns $16,000 to $32,000 a year in McKinsey’s classification scheme.

“Very wealthy” means pretty much what it says; 10 million CNY is roughly 1.6 million USD. That segment is projected to take a much larger cut of the luxury market in China, as the “wealthy” segment’s share recedes. Meanwhile, China’s lower-middle class and “mass affluent” class are giving way to its upper-middle—a curious trend that McKinsey explains as spending on experiences, like spas and weekend getaways. In the coming years, China’s famed obsession with red Bordeaux, Italian automobiles, and Swiss watches will become the sole province of the country’s superrich. Those who merely aspire to conspicuous consumption will have to make due with midtier brands.

The pattern is roughly the same in the U.S., as onetime aspirational consumers give up on Gucci (whose parent company’s stock is down 2.1 percent year over year, despite the 7 percent growth of its purported market). Their brands of choice now include the more reasonably priced Michael Kors, Uniqlo, and Topshop.

Those that cover the aspirational range—Armani, Prada, LVMH, and the like—are seeing the big bottom fall out from under them. And they’re being forced into a pickle. They can drop their diffusion pricing even lower, in a bid to win back the aspirational shoppers, but doing so might cheapen their brand image, sacrificing high-end customers in a fruitless quest to recapture the low end. Or they can let the low-end go, which would mean drastically culling product lines, scaling back operations, and hoping to compete with the 0.1 percent’s growing taste for bespoke and artisanal goods.

It’s a dilemma few will navigate gracefully. And it’s a dilemma we’ve seen before; it’s what happens when luxury markets bifurcate suddenly and dramatically. It happened most notably in the 1970s, when the Swiss watch industry nearly collapsed, and many long-lived fashion houses began to fail.

Not everyone will fail this time around. The brands that survive the culling will have to avoid the messy ground—the aspirational gap—between the upper-middle and the top of the market. On the low end, Uniqlo and Topshop will continue delivering fashion-forward basics at deceptively affordable prices. On the high end, look to unique or bespoke makers, particularly those with rich, regional heritage. China’s robber barons will tire of brand-name menswear and turn instead to increasingly upscale Hong Kong makers such as W.W. Chan. In the States, Ralph Lauren will find growth in coming years by moving its flagship brand name toward the top of the market while pushing its diffusion lines down into Uniqlo’s turf. It won’t cross the aspirational gap so much as set up camp on either side of it.

Not everyone will be so nimble. BMW has overextended itself by playing more and more in various entry-level aspirational markets; even BMW enthusiasts are confused about how many market segments, models, and diffusion lines the automaker sells today. With its wheels stuck in the mud, it will watch more agile competitors like Daimler AG (Mercedes) catching up in the rearview.

Luxury as we know it—as a consumer market, as a concept—is atomizing. Market-leading brands will buckle under the weight of their legacy product lines, and new brands will redefine the term along increasingly sophisticated segments of geography, socioeconomics, and cultural identity. Brands will have to choose which dream they’re selling; they’ll have to pick sides. If they don’t, they’ll pay a steep price for their indecision. We won’t be able to afford some of them, and that’s just as well—many of them can no longer afford us.

*Correction, April 16, 2014: This article originally misspelled the name of the Scotch whisky Johnnie Walker Blue. (Return.)