This is part of a special series about great rivalries: between tech titans, sports franchises, and even dinosaur hunters. Read about the series here.

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

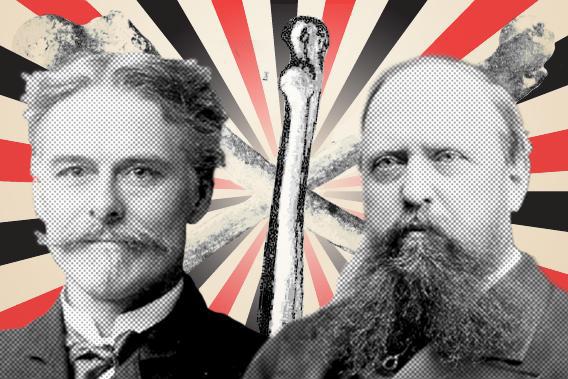

Before his unexpected death in June, James Gandolfini had signed on to star in another HBO project: Instead of playing the shrewd and short-tempered capo of a criminal organization based in New Jersey, he was to be the shrewd and short-tempered capo of a criminal organization based in New Haven, Conn. Instead of a Mafioso, he’d be a paleontologist. The movie was to be called Bone Wars, about the feud between two fossil-hunting academics in the 19th century: Yale’s Othniel Charles Marsh (Gandolfini) and Edward Drinker Cope (Steve Carell), eventually of the University of Pennsylvania. Their many years of vicious competition—played out across the Wild West, with secret deals and sticks of dynamite—left both men destitute and disappointed. They also produced the most amazing dinosaur discoveries the world had ever known: Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus, and scores of other species.

The ugly-tragic tale of Marsh and Cope has been recounted many times before, in documentaries, graphic novels, and lots and lots of books. As of 2005, you could even recreate the fracas on your coffee table with a deck of cards. (“Too much history, not enough fun,” one customer complained.) Its mass appeal relies in part upon the contrast of the characters: Marsh, cast in the role of the bald and bearded farmer’s son, a meticulous collector, a Darwinist; versus Cope, the gentleman scholar, a loosey-goosey science prodigy who did not believe in natural selection. The only things they had in common were their brilliance and ambition—qualities that set them on the path of mutually assured destruction. But the standard telling underplays a more fundamental rivalry: not that between Marsh and Cope, but one that set them both against a mild-mannered, older gent named Joseph Leidy.

Leidy’s work preceded that of his much more famous rivals. As the first paleontologist of vertebrates in the U.S., Leidy found evidence that horses, lions, rhinos, and other large mammals once roamed the country’s West. In 1856—a dozen years before the bone wars began—the ungainly professor made a more surprising discovery: America had dinosaurs. A few years later, Leidy published a description of the most complete dinosaur skeleton yet found, sent to him in Philadelphia by an amateur collector at the marl pits near Haddonfield, N.J. His work concluded that the Hadrosaurus foulkii was bipedal, a gigantic animal that reared back on its hind legs and tail.

By the late 1860s, young Cope had become, like Leidy, a member of Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences and started fossil-hunting in the Garden State. That’s where Cope and Marsh began their lifelong grudge. The two had met briefly in Germany, but the bone wars started with a visit that Marsh, already a Yale professor, made to Haddonfield in 1868. On his way out of town, Marsh bribed workers at the pits to send what bones they found directly to New Haven, bypassing Cope.

This subterfuge inspired further rounds of sneakiness from Cope and Marsh, and some from Leidy, too. In the early 1870s, all three men set out to look for dinosaurs out West, where the dry, mountainous terrain made fossils numerous and relatively easy to unearth. Marsh felt he had a prior claim to the sites near Fort Bridger in Wyoming, and he hired spies to monitor Cope’s travels in the area. (In communiqués with his employees, Marsh called Cope by a code name, “Jones.”) Marsh also tried to waylay fossils from the local diggers who had been sending finds to Leidy. And Leidy, for his part, encouraged them to hide the bones from Cope.

This three-way row played out in the scientific literature as well. In the spring of 1870, Leidy pointed out in public that Cope’s reconstruction of an Elasmosaurus had the skull attached to the wrong end, as if to make a creature with a long tail and a short neck, rather than one with a long neck and a short tail. Marsh later said he’d been the one to notice this mistake. “When I informed Professor Cope of it his wounded vanity received a shock from which it has never recovered, and he has since been my bitter enemy,” Marsh later wrote. “I give this transaction as one sample of Professor Cope and his methods—one taste of the cheese.”

In Wyoming, the fossil hunters each found evidence of a strange, elephantine beast with six knobby protrusions on its head. Leidy named it before the others—Uintatherium robustum—but the battle over primacy continued in the journals. Cope and Marsh came up with reasons to rename Leidy’s species several dozen times, as if they were making new discoveries on the basis of their own fossil finds. They fought ferociously as Leidy’s contributions were pushed off to the side. “[Marsh] repeats his statements,” Cope wrote in the American Naturalist in June 1873, “as though the Uintatherium were a Rosinante, and the ninth commandment a wind-mill.” When Cope added that some of his mistakes were the results of printers’ errors, Marsh replied, “As a sleight-of-hand performance with names and dates, [Cope’s explanation] shows practice, and is amusing, but to those familiar with the subject, and to moralists, it suggests sad reflections.”

“Poor Old Leidy” (as Cope called him) was far less confrontational than his younger peers and smaller in his speculations. Cope in particular would vividly describe his wild visions of the ancient world. “At night-fall, we may imagine them trooping to the shore and suspending themselves to the cliffs by the claw-bearing fingers of their wing-limbs,” he wrote in 1872, inspired by some pterodactyl bones.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Creative Commons.

By 1874, Leidy had decided to quit the field of paleontology altogether. He could not abide the endless sniping, nor did he have the money to compete. While Cope, the eldest son of a Quaker shipping magnate, and Marsh are often contrasted as gentleman and grind, in truth both were very wealthy. Marsh was born into a modest home, but his fantastically wealthy Uncle George sent him first to Andover and then to Yale. When Marsh joined the faculty in New Haven in 1866, it was in part because the family had donated $150,000 for the establishment of a natural history museum. Leidy had no such advantages. His father was a hatter, and Leidy spent his early years in research working extra hours for the city coroner. While Cope and Marsh could afford to hire men for outrageous expeditions, not to mention spies and double agents, Leidy didn’t have the budget or the will. The bone wars moved on without him.

By 1878, Cope and Marsh were bickering over bigger, more impressive claims in Colorado and Wyoming. Each paid his teams of diggers to work through the winter to help uncover evidence of fabulous dinosaurs from the Jurassic period: Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, and many others. The professors’ employees fought one another, sometimes throwing rocks and dirt or brandishing revolvers in the field. Some switched sides and others used a slash-and-burn approach to excavation, destroying bones so as to flummox late-arriving peers.

Their dispute made its way to Washington, D.C., where Marsh figured out a way to cut off Cope’s funding and tried to get the government to repossess his rival’s fossils. In 1890, Cope went after Marsh in the pages of the New York Herald. “Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare,” the headline read. “Red Hot Denials Put Forth: Heavy Blows Dealt in Attack and Defense and Lots of Hard Nuts Provided for Scientific Digestion.” Eventually, both men would lose both their funding and their credibility, and their careers would be forever linked by their quarrel.

What became of Leidy? If it hadn’t been for Marsh and Cope, and the way they bullied him aside, he might have continued on in paleontology and been far better known. “By all contemporary judgment, Leidy was one of the most outstanding American biologists of his century,” writes his biographer Leonard Warren in Joseph Leidy: The Last Man Who Knew Everything. “Yet he is relatively unknown today, even among people in that field.” When his younger rivals turned fossil-hunting from a scholar’s art into a contact sport, Leidy quit the team. Warren cites the preface to one of Leidy’s most important works on fossilized remains. It begins with a bit of modesty that doubles as an indictment of his more aggressive colleagues: “No attempt has been made at generalizations or theories which might attract the momentary attention and admiration of the scientific community,” he wrote. “We have endeavored to see and represent things correctly, nothing more.” By retreating from the battle in the West, Leidy erased himself from history and found a legacy of lasting inattention.

The bone wars did have a happy ending of a sort, because they nudged Leidy back to important work in other fields. After abandoning paleontology, he returned to other areas in which he’d long been interested. Before his work on the ancient fauna of North America, Leidy had been the country’s leading parasitologist. While Cope and Marsh went off searching for bigger, better bones, Leidy roamed the fish markets in Philadelphia, scouring the seafood entrails for novel parasites. Among his microscopic discoveries were the microorganism in pork that causes trichinosis and the source of canine heartworm. Leidy also worked in anatomy and pathology, and he used his skill with microscopes to help police distinguish human blood from chicken remains. He studied gems and minerals, too, and left his sizable collection to the Smithsonian.

It’s hard to say if anyone emerged the victor of the bone wars, but we do at least have scientific stats. By the end of the century, Marsh had discovered 80 kinds of dinosaur, and Cope found 56. But Joseph Leidy’s work described a wider world: In addition to some fossil beasts, he named at least 100 protozoans and 300 invertebrates. “Leidy was a man of facts,” writes Warren. “Because historians and popularizers of science are attracted to unifying principles and the clash of opinions, rather than to the recitation of data … there has been a tendency to let him rest in peace.”