In the 19th century, nullification was the idea that states could void the actions of the federal government if they deemed them unconstitutional. Its proponents, chief among them John C. Calhoun, argued that if something the feds were doing—i.e. tariffs—was contrary to the economic interests of the entity he cared most about—South Carolina—then the state could simply do its own thing. Nullification, like Calhoun’s ideas about slavery, was a profoundly bad one, and it led to a constitutional crisis.

Today, I’d propose a different meaning for nullification—and it is a reason for both hope and concern for anyone dismayed by the presidency of Donald Trump. There is always a tendency for powerful actors—in state and local government, yes, but also in the private sector generally—to decide not to do business with the president, and to act as if the executive branch’s policies don’t exist. In the Trump era that tendency has already become notably pronounced, and it comes in three principal forms.

One form of nullification is denial of patronage: refusing to do business with the entities the president or his family owns. One theory has suggested that the presidency would be a boon to Trump’s businesses, including his golf courses, his private club Mar-a-Lago, and the hotels that carry his name. But with each month, Trump’s conduct in office has pushed people and groups concerned with their brands to cease working with Trump properties. The Trump-branded public golf course in the Bronx, New York, saw its business decline in 2016. While Trump’s Washington, D.C., hotel attracts lobbyists and corporate events, most of the rooms are empty. (Its occupancy rate is a measly 42 percent.) Mar-a-Lago, a stalwart of the social and charity scene in Palm Beach, Florida, has been hit by a wave of event nullification. Since Trump’s disastrous series of comments about the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, one by one charities and nonprofits have canceled their plans to host luncheons, dinners, galas, and dances at the facility. The club, write Drew Harwell and David Farenthold in the Washington Post, has “lost nine of the 16 galas or dinner events that it had been scheduled to host during next winter’s social ‘season’ in Palm Beach. At least three other groups have also canceled charity luncheons there this week.”

A second form of nullification is denial of association: refusing to provide counsel or show up to photo opportunities, or to be in the same room as the president. In the early days of the Trump administration and during the transition, CEOs, athletes, and other boldface names dutifully showed up—some with glee, some with pained expressions on their faces—to be part of the photo ops and volunteer to serve on various councils.

But the norm is no longer the norm. CEOs, athletes, and celebrities are denying Trump the privilege of their association. After Ken Frazier of Merck and Co. quit the Trump’s council on manufacturing, an exodus of CEOs commenced. Several of the advisory firms set up to grant corporate legitimacy and support for the Trump presidency quickly disbanded: the Manufacturing Council, the Strategic and Policy Forum, the Infrastructure Council.

The people on these committees had significant business with the government, and hence much to gain and lose from changes in government policy. But they decided that having their personal or corporate brands associated with Trump would be damaging, cause an intolerable level of cognitive dissonance at a personal level, or both. As Merck lead director Leslie Brun told the Wall Street Journal about boardroom discussion surrounding Trump: “Informal conversations among board members often revolved around ‘what do you tell your kids?’ ”

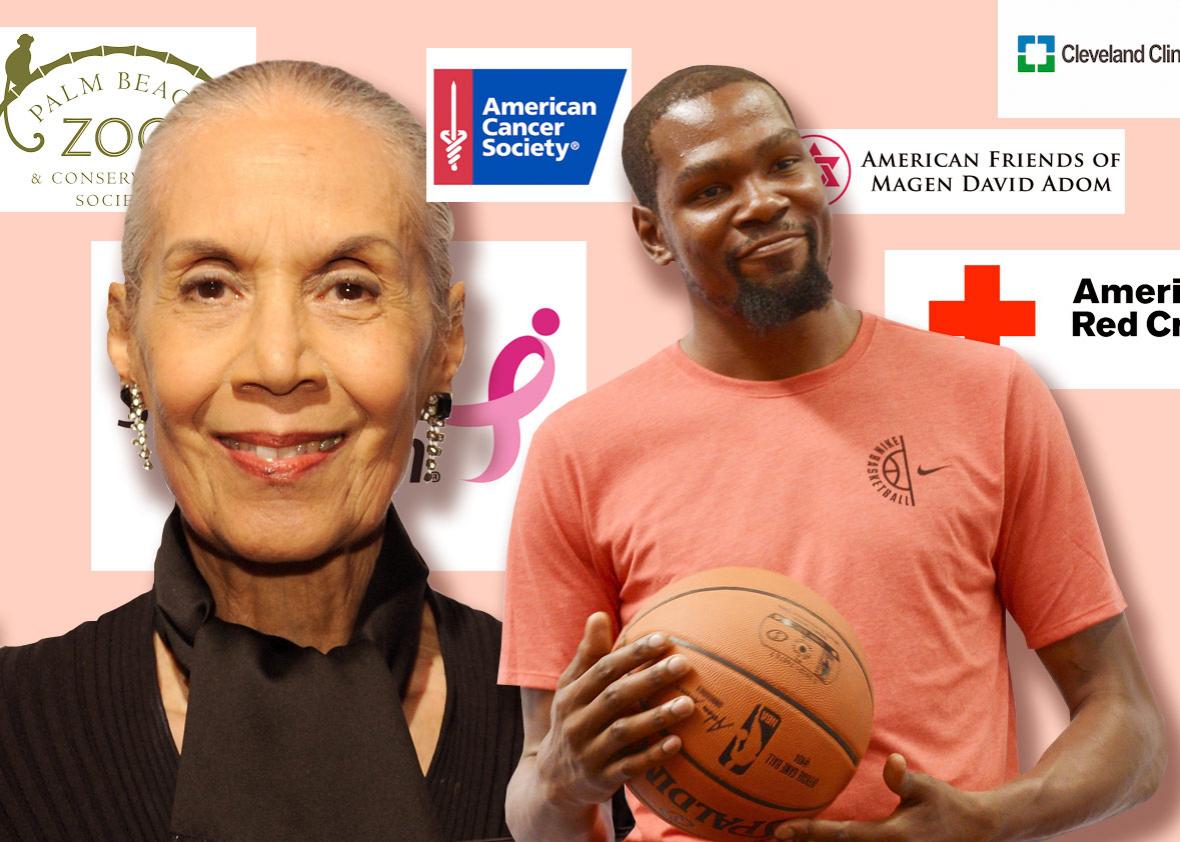

The Kennedy Center, about to toast six artists, breathed a sigh of relief when Trump said he wouldn’t show up to its annual Honors and canceled the White House reception associated with the event—this as some of the recipients, including actress and dancer Carmen de Lavallade, said they would not show up at the White House reception. Basketball star Kevin Durant of the Golden State Warriors said he would not go to the White House to celebrate his team’s victory in the NBA Finals, citing a lack of respect for its occupant. “I don’t agree with what he agrees with, so my voice is going to be heard by not doing that,” Durant said.

A third form of nullification is to act as if the proclamations, executive orders, and policy pronouncements are irrelevant to you, don’t exist, or are to be ignored—and to create alternate markets and realities. This dynamic can be seen most vividly in the energy and environmental arenas. Trump has promised to revive the coal industry, pulled out of the Paris climate accord, and installed a bunch of climate-change denialists and skeptics in relevant government agencies.

But states, cities, and companies make their own climate-change policy through laws, policies, standards, or procurement decisions. And many of them are actively nullifying Trump’s statements and actions.

Here are a few things that have happened so far this year:

California extended its cap-and-trade program through 2030. Hawaii became the first state to commit to having 100 percent renewable energy on its electricity supply grid. Orlando, Florida, adopted a target of getting all its electricity from renewable sources by 2050, joining the growing roster of more than three dozen cities that have done so. JPMorgan Chase said that by 2020, it would power all its operations through emissions-free energy. The bank has joined more than 100 large multinational corporations that have made the same commitment. Through May, utilities announced the closure of eight coal-burning plants as the industry continues its transition to a lower-carbon future.

This is not to say Trump doesn’t have real power or that his administration isn’t affecting change or delivering results to favored constituencies. Whether it is the Environmental Protection Agency rolling back water regulations, general nonfeasance at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, or the Justice Department’s enforcement of immigration policies, the Trump administration is changing realities on the ground. The rise of nullification does not decrease the danger of an unfettered Trump administration.

What’s more, nullification isn’t a particularly good precedent. I would argue that it is much better for the country and our economy when all sorts of people feel comfortable visiting the White House and making common cause with the White House—and when states, cities, the federal government, and companies are on the same page in the pursuit of goals. There are good historical, constitutional, and practical reasons for the federal government to have primacy over states in many areas. And while it’s nice that some companies are relatively progressive on some issues, and that some CEOs can muster the moral courage to take stands, we shouldn’t be relying on them excessively. CEOs of defense contractors have a much harder time acting as if Trump doesn’t exist than, say, CEOs of consumer products or technology companies. Bench players and role players have far less leeway than all-stars to express their political views.

Still, nullification offers something more satisfying than catharsis or schadenfreude. The fact that people, institutions, and organizations are willing and able to deny their dollars and association with Trump and be celebrated for it is a sign that America’s democratic and market system, which has been under attack, is holding up strong.

One of the features about authoritarian regimes is that there is a price to be paid for defying the expressed wishes and whims of the government and its leader: You can lose your business, or get jailed, or get frozen out from contracts, or lose your license. That’s not happening here.