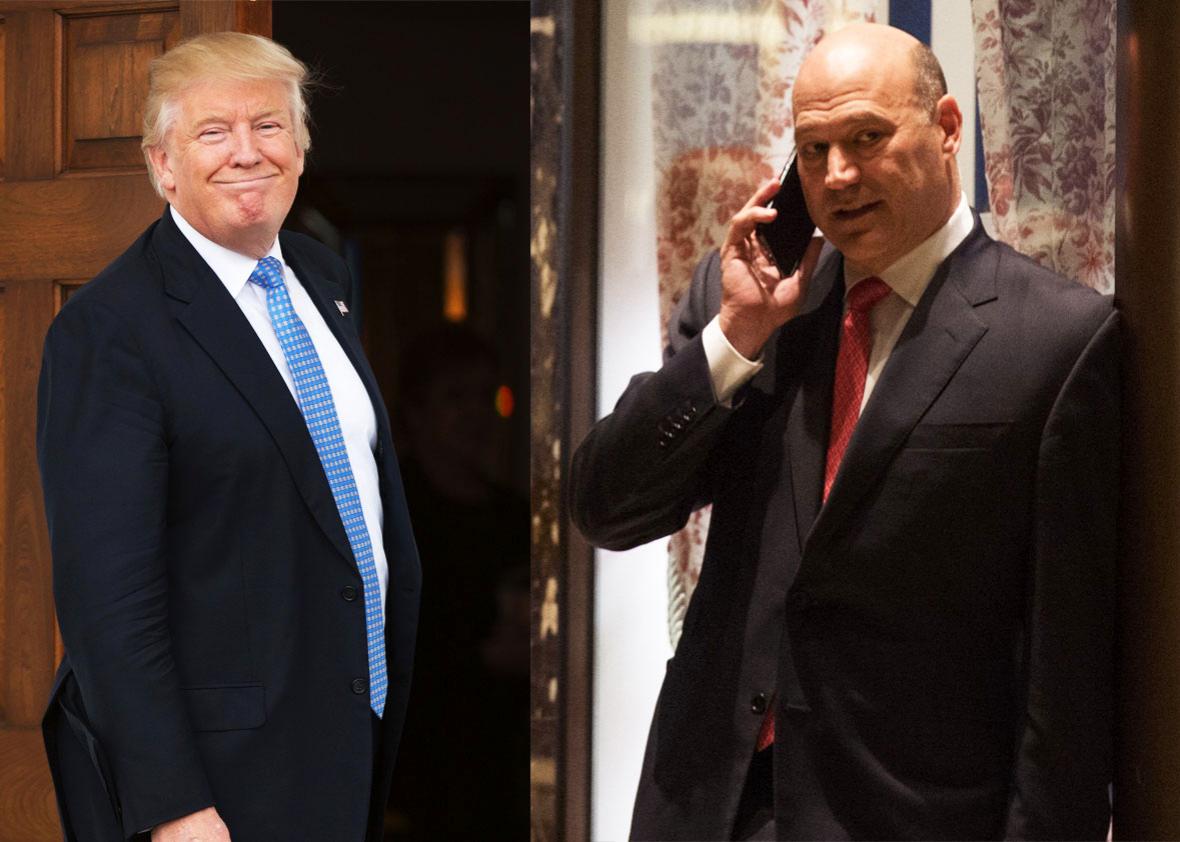

President-elect Donald Trump will reportedly name Gary Cohn, the longtime chief operating officer at Goldman Sachs, the director of the National Economic Council. If you’re keeping count, that would be another Goldman alum in Trump’s orbit, in addition to: former Goldman banker (and former Breitbart honcho) Steve Bannon, set to be a key White House adviser; former Goldman partner-turned-bubble-surfer Steven Mnuchin, who will head the treasury; and former Goldman banker Anthony Scaramucci, now a key transition adviser.

Is it a betrayal to hire men like Cohn, who the last time I saw in person was fist-bumping a bartender at Davos?

After all, Trump lambasted Hillary Clinton for giving highly compensated speeches to the investment bank and trashed Sen. Ted Cruz because his wife worked there, and a closing campaign ad scaremongering about current Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein looked as if it might have first run in the Völkischer Beobachter.

So, yes, you could read Cohn’s appointment as another sign of hypocrisy, more proof that the Trump campaign was just a carny act. But it’s also something else: a sign that some aspects of the system are working exactly as they’re supposed to, and long have.

Cohn, a 25-year veteran of the firm, is very much a central cog in the global financial establishment. And in accepting the position, Cohn is simply following a well-worn path. Government service—particularly the National Economic Council—is what top Goldman executives do when their careers have run their course.

The National Economic Council was created during the first year of the Clinton administration. Its inaugural director was Robert Rubin, the co-head of Goldman Sachs who was an influential early Clinton adviser. After two years at NEC, Rubin was promoted to Treasury Secretary. Rubin’s partner in running Goldman in the 1990s was Stephen Friedman. Friedman left the firm in 1994 but in 2002 was named to succeed Larry Lindsey as—yup—director of President George W. Bush’s National Economic Council.

Friedman and Rubin were succeeded at the helm of Goldman by Jon Corzine, who went on to run successfully for U.S. Senate and then governor after he was ousted in 1998. Corzine was replaced by Henry Paulson, who had been the chief operating officer. And when Paulson’s time at chief executive at Goldman came to an end, he skipped the NEC and went directly to the Treasury Department (thus forcing me into the public humiliation of eating a chapter of Dow 36,000.).

Unlike Paulson or the other Goldman execs who went on to head the NEC, Cohn never made it to the top. Indeed, one of the strange features of the past several years has been a certain stasis at the head of America’s largest financial institutions. Jamie Dimon has been running JPMorgan Chase for 12 years, through crisis, cancer, and a mammoth list of fines, yet shows no signs of giving up. Brian Moynihan is completing his sixth year as CEO as Bank of America. And Lloyd Blankfein, the CEO of Goldman Sachs, is now entering his second decade in the role.

One could have imagined Blankfein taking a job in the Clinton administration. (His beard, self-deprecation, and liberal social views mark him as a Democrat.) But the results of the November election foreclosed that option. For an ambitious heir apparent at Goldman, which Cohn has been for the past several years, the only way up is out.

Like many of those who thrive at Goldman, Cohn is affable in public; hard-driving, tough, borderline-arrogant in private; political but not particularly ideological. A graduate of American University, Cohn is a little bit like the less-charismatic, brawnier younger brother to Blankfein.

Cohn made and left his mark first as a trader, and then as the chief operating officer, making sure the highly functional bureaucracy of the global banking giant runs efficiently and managing internal rivalries—not as a big-picture strategist or the public face of the firm.

Some of the early buzz surrounding Cohn was that he was to be considered for the Office of Management and Budget, which is an important operational job—one has to manage a large staff, the production of key documents, and the nasty negotiations surrounding budgets. OMB directors spend a lot of time in the weeds.

The National Economic Council is a much different type of operation. It’s a talking shop and influence sorter. As such, it is perfect for habitués of what used to be a secretive private partnership. It doesn’t have a large workforce of far-flung offices to manage. The director doesn’t have to be bothered much with operations, personnel, ribbon-cuttings, and pointless meetings. The job is twofold. First, the NEC director serves as one of the administration’s private-sector whisperers—talking to CEOs, drumming up outside support for policies, providing comfort to executives who might be concerned about the president’s policies and behavior. Second, the director functions as a sort of traffic cop and counselor for the conflicting power centers of policy and analysis within the administration. The job consists largely of sitting in very nice conference rooms, entertaining visitors seeking favors, attending high-end conferences, cajoling peers, participating in phone calls, and leaking selectively to favored press.

It’s kind of like being the CEO of a big investment bank—except without the big salary.