This article is drawn from Cathy O’Neil’s book Weapons of Math Destruction.

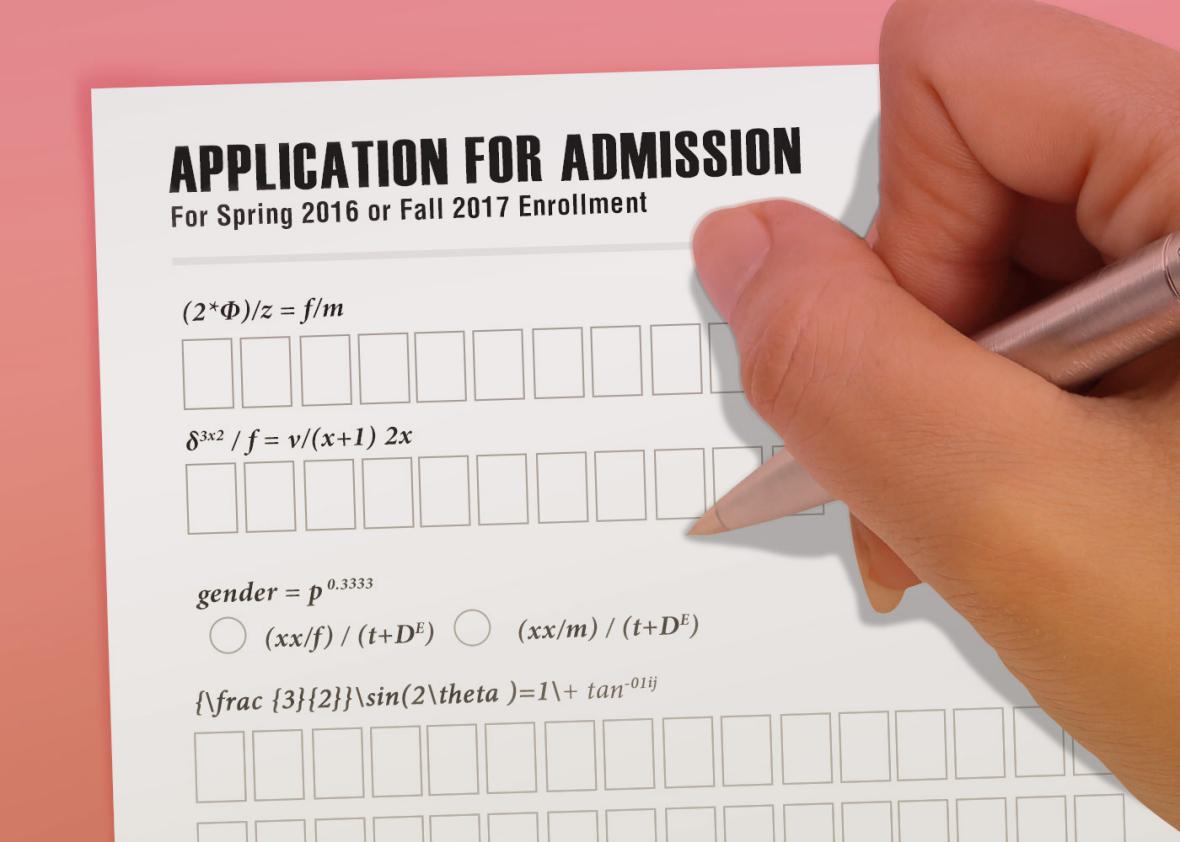

It’s September, so if there’s a high-school senior in your life, you’re getting down to work on college admissions. A generation ago, that meant visiting a few campuses, ponying up application fees, and filling out forms. That seems quaint now. Today’s college admissions process has gradually become dominated by a viper’s nest of competing algorithms that keep tuitions rising, parents worrying, and kids suffering. Fail to play the game, and your child may pay the price.

This phenomenon has attained arms-race status in recent years, but it isn’t exactly new. The earliest and most influential algorithm is the U.S. News & World Reports college rankings. The U.S. News rankings rely on a questionable and opaque scoring algorithm, which changes over time and may or may not reflect a given person’s tastes. But then again, people like scores, since they seem clean and objective and vaguely mathematical and smart. So the conclusions of the U.S. News list have become received wisdom to many frantic parents. In fact, it’s been so influential that the role of many college administrators has gradually changed from improving academics to improving their colleges’ rankings, at whatever the cost.

At times their desperation has led schools to lie and cheat. Bucknell University lied about SAT averages from 2006 to 2012, and Emory University sent in biased SAT scores and class ranks for at least 11 years, starting in 2000. Iona College admitted to fudging SAT scores, graduation rates, retention rates, acceptance rates, and student-to-faculty ratios in order to move from 50th place to 30th for nine years before it was discovered. Law schools that want to buff up their recent graduate employment numbers have been known to temporarily hire some of those former students or even count nonresponses to employment surveys as “employed.”

Even when schools stop short of outright fraud, they do all they can to appeal to the ranking system, which means inferring the proxies that the underlying scoring system uses. It’s called gaming a system, and college administrators are experts.

Rankings go up if colleges appear exclusive, which is determined by various metrics including what proportion of applicants get accepted (better to be low), what proportion of accepted applicants actually enroll (better to be high), and what the average SAT score is of those enrolled. That means there’s stiff competition for the high-end student, and things like extremely plush living quarters and fancy athletic facilities—some even equipped with lazy rivers—are becoming par for the course. There’s nothing inherently academic about most of these changes, but they cost money, both in their construction and in the number of administrators it takes to arrange it all.

The more the model is gamed, the more expensive colleges become. There’s no penalty for high tuition, because the U.S. News model doesn’t track cost. Over time, the widespread gaming has led to outrageous tuitions but not necessarily a better education. The pool of high school kids hasn’t changed much, but that hasn’t stopped the college system from entering an expensive arms race of prestige. The more prestige, the more students apply, and the more you can reject—thus, greater selectivity, higher U.S. News ratings, and—presto—still more prestige. Those who have, get.

Enter the age of big data. Recently, college admissions offices have begun to use algorithms that work on an individual-student basis to profile and predict their behavior. They use social media data, as well as the data supplied by the applications, to compute the likelihood a given student will enroll if accepted, the extent of financial aid needed by the student—or needed to seduce a relatively well-off student—and the chances that student will graduate. It’s the big data version of the exact same game, with the exact same goal: to increase the college’s ranking.

Because of the increasing scrutiny and reliance on predictive algorithms, life has become increasingly miserable for high school kids. For example, we may as well hold a funeral for the concept of the safety school, since high acceptance rates are bad for rankings.* That means more and longer levels of anxiety senior year while waiting for acceptance and rejection letters. An indication of this anxiety is displayed in the number of schools high-school seniors are applying to; the number of students applying to at least seven has tripled since 1990, from 9 percent to 29 percent.

Application preparations start earlier and earlier, with SAT prep, homework tutoring, and intense after-school activity regiments creeping into a student’s middle-school years. We are inching toward the Chinese model, in which students are routinely expected to study many hours per day for the national gaokao exams. Widespread cheating scandals might not be far behind, because that’s what happens when the stakes are set so high and when we have to look good for the algorithms.

There’s help, at a cost. Professional consultants like Stephen Ma claim to have their own predictive algorithms that will game the system for their child. Ma told Bloomberg Businessweek in 2014 that he charged one set of parents $25,931 to help their child get an offer from New York University.

What about poor kids? There’s an algorithm for that. The College Board website has a matching algorithm to pair high school students with suitable colleges, and it’s free. This could be a useful tool for many. But the college readiness advisors I interviewed said their inner-city students are almost entirely paired with expensive for-profit universities, the diplomas of which have been shown to be no more useful in landing jobs than high-school diplomas.

For-profit colleges have been making heavy use of big data algorithms. Apollo Education Group, the parent company for the University of Phoenix, spent more than a billion dollars on marketing in 2010, almost all of it focused on recruiting and much of that money going to Google and Facebook in the form of tailored ads. (Full disclosure: Slate is a subsidiary of Graham Holdings Co., which also owns Kaplan, a for-profit education company.)

If you didn’t see those ads, don’t be surprised: They were specifically designed for people who were eligible for financial aid, often poor single mothers, recent immigrants, or veterans desperate for a new life. They are the people who allow for-profit colleges to game the federal aid system itself and who are vulnerable to quick-fix promises. The good news is that the system is starting to give way: Corinthian College was shuttered in 2015, and ITT Technical Institute announced this month that it will shut down.

The college admissions process has become a minefield, and the current algorithms are the mines. If we are to regain control over our education system, we need to do better, and that means a better definition of quality education, with an eye on containing costs. We can start by demanding college rankings, for example, that are tailored to our needs and that take into account cost and future debt loads. The U.S. Department of Education’s College Scorecard is a great start. Big data can help but only if we scrutinize the algorithms instead of unquestionably following them.

*Correction, Sept. 16, 2016: This article originally misstated that high rejection rates are bad for colleges’ rankings. High acceptance rates are. (Return.)