Why are we here?

Obamacare is starting to look a little wobbly. Big insurers are bailing on the public insurance exchanges that were set up under the Affordable Care Act, ostensibly because they can’t figure out how to turn a profit selling coverage through them—which both means shoppers in some states will have fewer options when it comes time to buy their coverage for 2017 and calls into question the long-term stability of the entire massive health care reform. Meanwhile, insurance premiums appear to be headed for a major hike next year.

Oh dear.

Indeed! If Donald Trump weren’t busy going Full Metal Jacket on his own presidential campaign, CNN would have been gabbing about this all last week.

So is Obamacare turning into the disaster Republicans have always predicted?

No, not yet. But as Kaiser Family Foundation senior vice president Larry Levitt put it to me, “There are certainly red flags” that we all ought to worry about.

Can you explain in reasonable detail why I should be fretting?

Last week, Aetna, the country’s third largest health insurer, said it would give up selling coverage on Obamacare’s official marketplaces in 11 out of 15 states after losing hundreds of millions of dollars on the business. That made it the third major carrier this year, after Humana and UnitedHealth Group, to announce it was pulling back from the exchanges because they were unprofitable.

Aetna’s move is worrisome for a couple of reasons. In the short term, it simply means there will be fewer insurers for consumers to choose from on the marketplaces in 2017. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s latest count, there are currently five states—Alabama, Alaska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wyoming—where just one carrier is planning to participate in the Affordable Care Act exchange. At least one place, Pinal County in Arizona, is down to zero insurers for now.

And in the long term? The trouble Aetna and other large carriers have had selling Obamacare plans is making some people wonder whether the law will ever work as intended.

Wait. I saw some pissed-off tweets about Aetna and a merger. What’s the deal with that?

Aetna’s precise motivations for abandoning the Obamacare exchanges are a bit murky. During an investor call, the company claimed it was a purely financial decision. However, the Huffington Post discovered a letter from July in which CEO Mark Bertolini told the Justice Department that Aetna would pull out of some Obamacare marketplaces unless regulators approved its proposed merger with Humana. Uncowed, the government sued to block the deal anyway. Some have suggested that Aetna is retreating to spite the administration after failing to threaten it into submission. But it’s also possible the merger would have made staying on the exchanges, and risking a few more years of potential losses, more financially sustainable. Maybe it’s a mixture of the two. For our purposes, though, I’d argue that such speculation is a distraction. Nobody doubts that Aetna has been losing money on the exchanges. As far as the future of Obamacare is concerned, that’s the key fact.

Minerva Studio/Thinkstock

But I thought Obamacare was working fine. I’m pretty sure you told me Obamacare was working fine!

Obamacare is expanding coverage, which is fantastic. The U.S. uninsured rate fell to 9.1 percent last year, its lowest mark ever. The question is if the marketplaces can enroll more customers and become self-sustaining, or if we have to worry about them collapsing into what economists call an “adverse selection death spiral” one day.

Cue the ominous music.

But before we get into how Obamacare has stumbled, let’s talk about how it’s supposed to work. The Affordable Care Act was designed to help Americans purchase health coverage by subsidizing private insurance sold through carefully regulated state marketplaces. In other words, it’s supposed to be a private-sector-friendly solution to universal health care, because there was no way in heck Congress was voting for fully socialized medicine in 2009. To make sure everyone could get covered, it barred companies from discriminating against customers with pre-existing conditions and limited how much more they could charge older buyers than younger ones. Sick, middle-aged people tend to cost insurance companies a lot of money. So in order for a system of private insurance to work, insurers need to be able to earn a profit. “We can’t expect health plans to continue participating in markets where they’ve been losing money,” said Caroline Pearson, senior vice president of strategy and policy at the health care consulting firm Avalere. That’s why the law tries to prod all Americans into buying insurance by taxing them if they don’t—that’s the “individual mandate.” The idea is that healthy customers will balance out the ill ones, and we’ll get a close-to-universal health care system that works.

But many insurers, like Aetna, have still been losing money. That’s probably in part because some companies deliberately underpriced their plans early on to win over customers. But insurers have also had trouble signing up enough young, healthy, and profitable adults to balance out the older, sicker patients with high medical costs that they’re required to cover under the reform law. The market is also smaller than expected—where the Congressional Budget Office once projected that 21 million Americans would purchase coverage through the exchanges this year, only 11.1 million were enrolled through March. “The first 10 million were really sick and the other 10 million never materialized,” Pearson told me. “That’s been the real challenge.” A McKinsey report concluded that in 2014, insurers lost about $2.7 billion on the individual market and probably more in 2015. There’s scant evidence things have improved since, which is especially worrisome since the individual mandate’s tax penalty fully phased in this year.

Obamacare’s architects knew the law would require a rocky transition period as insurers got a feel for the market, and so they created a pair of temporary programs, risk corridors and reinsurance, to cushion insurers’ losses if they got stuck with too many costly patients. But those are set to expire next year (a third program, called risk adjustment, is permanent), because the law’s drafters had expected the market’s risk pool—the mix of sick and healthy customers—to begin stabilizing.

With losses mounting and safety valves about to disappear, insurers have been asking state regulators to let them raise rates by quite a bit next year. Nationwide, carriers are asking for a 23-percent increase, on average, according to Charles Gaba of ACASignups.net, though in some states the average is more than 50 percent. Those are only requests, of course. Insurance commissioners can reject them. In the past, frightening headlines about double-digit rate increases turned out to be mostly hype; through this year, premiums actually turned out to be lower than projected. But as Margot Sanger-Katz explained in the New York Times in May, it’s widely believed that with insurers still burning cash and reinsurance and risk corridors on the way out, a lot of those eye-popping increases will get approved this year.

Does that mean Obamacare is about to become crazily expensive?

Not necessarily. In fact, a lot of customers won’t see much change at all, since Obamacare’s subsidies cap their payments at a percentage of their income. But families that don’t receive subsidies because they earn more than 400 percent of the poverty line could certainly see their premiums go up. (It’s always worth remembering that massive, unexpected price jumps were a regular feature of the pre-ACA market, which had far fewer consumer protections.)

Assuming this year’s increases are as large as the experts expect, the big unknown is whether they’ll be a one-off adjustment. If they are and future increases are smaller, then there isn’t much to lose sleep over. But if they scare off more Americans from buying individual insurance the next year, or convince healthy, middle-class customers to drop their care, you might see more big hikes down the line.

The absolute worst-case scenario is that death spiral I mentioned—this is the extinction-level event that haunts liberal health care wonks’ dreams—in which price increases push healthy consumers out of the market, leaving behind costly sick and old enrollees, leading to more price increases until the insurers flee and the whole market just collapses on itself. Conservative policy types will tell you that we might already be heading down that road. “It’s too early to say for sure that we’re in the death spiral,” Brian Blase, a senior research fellow at the libertarian-leaning Mercatus Center, told me after the news of Aetna’s pullout. “But I think the evidence is consistent with a death-spiral story.”

Minerva Studio/Thinkstock

Oy. This sucker is going down, isn’t it?

I wouldn’t say that. I mean, it’s not like the SS Obamacare has slammed into an iceberg and water’s gushing into the hull. McKinsey, for instance, has argued that as long as the government keeps offering subsidies, the system should be able to soldier on. Plus, large insurers aren’t giving up on the marketplaces entirely. Take Aetna again. According to its latest Securities and Exchange Commission filing, the 11 states where it’s pulling back from the marketplaces only account for about 20 percent of its Obamacare business. (It had 838,000 exchange customers as of June.) Even in the states from which it’s retreating, the company plans to continue selling coverage off the exchanges, which under the law would allow it to return to the marketplaces in 2018 should it feel so inclined. Meanwhile, Cigna is bucking the trend and plans to expand its marketplace footprint.

And don’t forget: Some insurers are making money on the exchanges. The difference is that companies like Centene and Molina got their starts working with Medicaid patients and have won over low-income Obamacare customers by offering inexpensive plans with narrower doctors’ networks. In a lot of ways, they’re more naturally suited for the exchanges than big names like Aetna and UnitedHealth, which really make their bones selling plush coverage to employers.

Of course, nobody imagined that Obamacare would be a place where middle-class families went to buy Medicaid-like health care. Ideally, the market would expand and evolve so insurers could make money offering robust plans at reasonable prices. But in much of the country, we’re not quite there yet.

Is Obamacare working properly anywhere?

Yes. Right now, Obamacare seems to be working much better in some states than others. In California, more than three-quarters of providers managed to squeeze out a profit in 2014, and residents have a whole slew of carriers to choose from. In rural states and the South, where populations are sparser and the residents often unhealthier, things have gone far less smoothly.

Some states may be suffering from a bit of self-sabotage. As Charles Gaba notes, insurance companies have tended to ask for higher premium increases in states where lawmakers (irrationally) declined to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, because they just hated Barack Hussein Obama that much. Their obstinance probably pushed a lot of low-income, not-particularly-healthy patients into the Obamacare exchanges, where they could get highly subsidized coverage. Some states also allowed residents to retain old plans that didn’t meet the Affordable Care Act’s standards through 2017, which kept those customers off the exchanges. They’ve also seen insurers ask for bigger hikes.

In the end, though, the Affordable Care Act is a national law that needs to work everywhere. And it doesn’t yet.

“In many parts of the country, it’s not whether the law can succeed. It’s what the choices for consumers will look like,” Kaiser’s Levitt told me. “But there are parts of the country where there is a legitimate question about whether the law can succeed at all. Perhaps ironically, that tends to be in more conservative states.”

Minerva Studio/Thinkstock

So, what are Obamacare’s big design flaws?

There are a lot of progressives out there who are probably shaking their heads and saying “I told you so” about the public option. There needs to be some sort of a backstop to ensure every county in the U.S. has insurance option on the exchanges. Otherwise, you get situations like Pinal County. Even if it didn’t have the pricing power of Medicare, as many on the left would prefer, a government-sponsored plan would have at least been a reliable fallback measure. The two watered-down replacements Congress passed instead haven’t really worked out. Nonprofit co-ops have been going bust, thanks to all the same market pressures facing private insurers. And a plan for the federal government to contract with private carriers to offer coverage in all 50 states hasn’t really materialized.

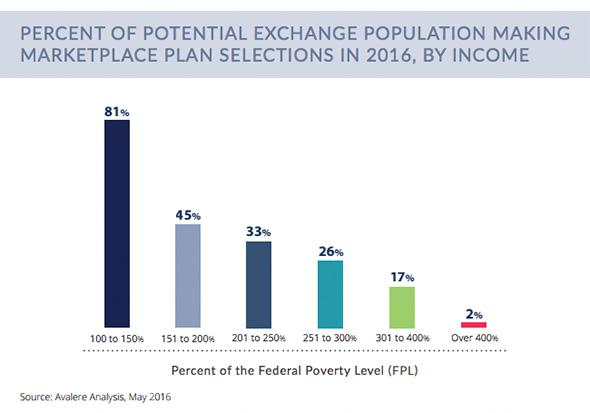

Beyond that, it seems pretty clear that Obamacare’s subsidies haven’t been generous enough to lure middle-income families. An Avalere anlaysis found that among eligible Americans between 100 and 150 percent of the poverty line, 81 percent were enrolled. That number drops to 17 percent among those between 301 and 400 percent of the poverty threshold.

Avalere

A conservative might look at that issue another way and say healthy middle-class households looking for inexpensive coverage should never have been forced into the same market as sicker patients who drive up costs for everyone—which is why they advocate special subsidized high-risk pools that provide separate insurance for the seriously ill. But you can have a long debate about whether those would be effective.

Insurers, for their part, have complained that Obamacare’s special enrollment periods, which let Americans sign up for coverage outside of the normal open-enrollment window, have driven up their costs by letting people buy coverage right when they get sick, then drop it once they’re well. While the administration has taken some steps to stop customers from gaming the system this way, it may need to do more.

And beyond all that, lawmakers probably should have given Obamacare a little more time to ramp up by extending the reinsurance and risk corridor programs beyond 2017. Both are actually permanent features of Medicare’s prescription drug coverage, which might have been the right route for Obamacare.

Of course, getting Congress to agree on a public health plan, bigger subsidies, or extending the backstops is going to be darn near impossible so long as Republicans are in control. The best the law’s supporters can probably hope for at the moment is an intensive enrollment drive in 2017 and the possibility that more people will decide they’d rather buy insurance than get whacked with the individual mandate penalty.

So when will we know if everything is working out OK?

I’ll let Larry Levitt take it away:

“I think a lot hinges on the next open enrollment period, partly because of premium hikes, partly because of insurers pulling out. If enrollment grows in 2017, I think a lot of these concerns will fade. If enrollment stagnates, I expect that to trigger a debate over how to fix the law. The problem is that Democrats and Republicans have big disagreements about what fixes to the law look like.”

So buckle up. This debate isn’t going to get less messy anytime soon.