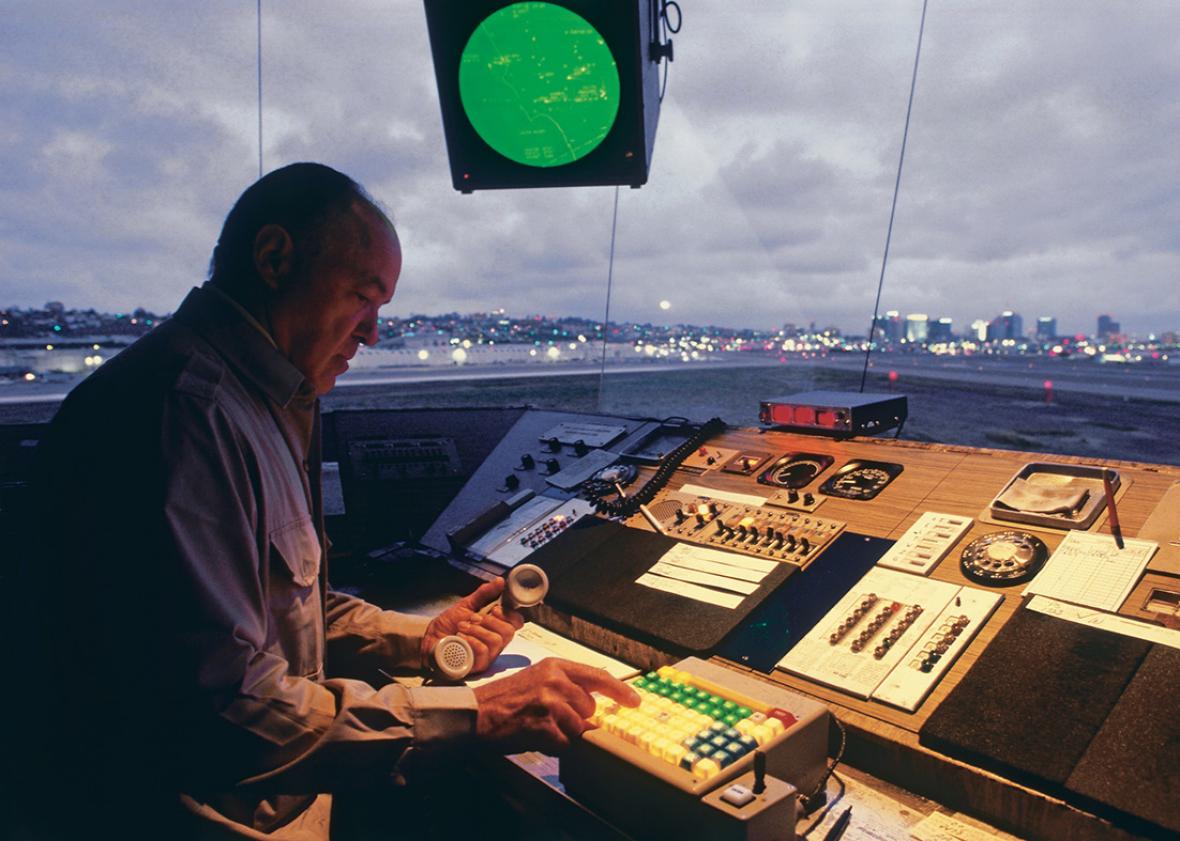

On Aug. 5, 1981, in response to a massive strike that threatened to ground all of American air travel, President Ronald Reagan fired 11,345 air traffic controllers at airports across the United States. In the immediate aftermath, military controllers filled in, but ultimately, the seasoned, striking controllers were replaced by a group of young upstarts.

Now those upstarts are retiring, and once again we’re facing a drastic shortage of trained air traffic controllers. Last month, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s inspector general issued an alarming report arguing that, in the coming years, it will be difficult for the Federal Aviation Administration to keep fully trained and adequately experienced eyes on radar screens at some of the nation’s busiest airports. The “FAA has not yet established an effective process for balancing training requirements with pending retirements,” the Office of Inspector General says in a statement—even though prior reports had highlighted the same issue in 2012, 2002, and 1986. Even in 1981, when Reagan first lowered the ax, anyone capable of simple math could have seen the issue coming: New hires, all roughly the same age, would eventually retire at roughly the same time. But then and now, very little was done.

This might sound like a minor pain at worst. The labor market tends to sort itself out, after all. If there aren’t enough controllers, then the FAA just has to entice applicants by offering a higher starting wage, right?

Unfortunately, that isn’t happening, and the controller shortage is already here. The FAA has a staffing plan in place for its critical facilities through 2017, but as the Office of Inspector General has pointed out, because trainees often count as full-fledged controllers at air traffic facilities, many are effectively understaffed at this very moment. And, as many control tower managers report, “on-the-job training requirements for trainees limit their contribution.”

Shortages in crucial workforces aren’t limited to air traffic. Across sectors, the aging of the baby boomers is leading to heightened retirement rates. In certain fields, that’s no big deal. Postal workers, for instance, constitute the oldest workforce of any industry, but their retirement will be relatively manageable, because entry-level Postal Service positions don’t require much training.

Retirement is also a relative nonissue for fields with high barriers to entry—as long as those fields contain exceedingly desirable jobs. No one’s worried about a retirement brain drain in the personal tech sector or investment banking, for instance. And in certain medical specializations, such as dermatology, there are plenty of new workers every year.

But almost across the board, jobs that are less than sexy and have high barriers to entry are now practically begging for trained workers. Within medicine, general practitioners and, ironically, geriatricians fall into this category. In the broader economy, entire sectors are experiencing retirement pressure. Take agriculture: As of 2012, the average age of principal farm owners is 58.3; 12 percent of them are older than 75. (Because it’s very expensive to buy a farm or start a new one, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has debuted a service that helps young, well-trained farmers work with older owners toward taking over their farms.)

Energy production and distribution companies—which already rely on an aging workforce that is more than a decade older than the average American worker—are desperate to find new talent. Not even the venerable Hoover Dam is exempt. “Roughly two-fifths of the workforce at the federal facility will be eligible to retire within five years, leaving the Bureau of Reclamation scrambling to recruit and train skilled workers while keeping one of the nation’s most important water and power facilities operational,” the Las Vegas Review-Journal reports.

In these cases and many others, should a large number of older workers retire en masse like they’re threatening to do, even raising wages for entry-level positions wouldn’t necessarily fill the gap left behind, because years of specialized training are required, and there’s a fixed number of trainees in the pipeline. It adds up to a system that’s not flexible enough to respond to the sudden changes that are very likely on the way. And in the meantime, the nation’s lights need to be kept on, the sick need to be healed, and aircraft need to be kept in the air. A three- to five-year period with understaffed vital economic areas, from air traffic control towers to wheat fields, is simply not an option.

Despite its birthrate, which is well below the replacement rate, the United States is in much better demographic shape than many other developed countries. Most importantly, it does not have a shrinking population—a fact it owes almost entirely to immigration. In countries such as Italy, Japan, and Germany, population loss is direr, and the lack of young workers in key roles is more acutely felt. In Germany, for instance, 2 out of 3 small- to medium-sized firms surveyed told accountancy firm Ernst and Young that it was difficult to find qualified workers. More than half of those surveyed said they believed the country’s recent influx of refugees from Syria would help alleviate the shortage.

Even the U.S.’s robust immigration can’t help the defense industry, whose classified work—involving positions ranging from office workers to engineers to welders—often requires extensive background checks and U.S. citizenship. And in other fields, no one wants to do those jobs, period. Even the last professionals you’ll ever encounter—funeral directors and morticians—are well into their 50s on average and aren’t being replaced as they retire.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the waves of retirements now facing the U.S. is how predictable it all has been. The government and private sector alike should have been actively working to counteract these forces, shepherding students to specialize in high-value, low-visibility fields. Instead, we may well face a harrowing stretch of years when our most expert professionals go missing from the positions where they’re needed most.

Contributing to the problem are attractive fields such as investment banking and computer programming. (Wall Street firms, which are taking measures to avoid losing top talent to Silicon Valley, still have no trouble filling entry-level seats.) Part is due to a communication breakdown between demographers and the general public. To the extent that the need for science, technology, engineering, and math training gets through to students, vital information about what to do with that training doesn’t. Proficiency in STEM alone does not guarantee a career that is mission-critical to a functioning society.

But the bulk of the issue is far is simpler: We don’t like to think about old age and what it means. The media generally doesn’t want to cover it, and people don’t want to read about it. It’s just a little too real and makes us just a little too uncomfortable. So, far too often, we grapple with the broad effects of aging only when it’s too late to avoid a bad outcome.

In the near future, thanks to declining birth rates, the aging of the baby boom, and extended longevity, more of the population will be older than ever before. Let’s not ignore what’s perhaps the biggest fully predictable change we’re facing as a society, simply because old age is challenging to think about. Life begins, and life ends. Once we accept that, we can work to make sure that what we do in the middle is as worthwhile as it can possibly be.