You could say I have a sentimental attachment to the chain bookstore. Growing up in an intellectually impoverished American suburb, I spent much of my free time in now-defunct locations of Borders and Barnes & Noble. I read garbage, mostly: popular history magazines, Star Trek novelizations, art tomes whose pages I scoured only for frank depictions of naked women. But I had an intuitive sense that all those “wordy” books sleeping on the shelves, whose spines I raced my finger along while traveling between the café and the restrooms, would some day be the building blocks of a real, adult mind, the cathedral-like dimensions of which I could almost picture emerging through the haze of my juvenile enthusiasms. Inside Barnes & Noble, the figures of great literature literally looked down on me. A large wallpapered mural assembled them all in some grand ahistorical café. It was through that mural that I had my first encounters with the brooding fop Oscar Wilde and the fabulously bearded Anthony Trollope.

As much as I lived in and grew to love this big box of books, I eventually realized my consumer behavior there may have contributed to its decline. At Borders, the only thing I would purchase was Snapple peach-flavored iced tea. At Barnes & Noble, I bought nothing at all. This problem—the loafing-but-not-buying problem—is nothing new to the bookselling trade. In a 1936 essay, George Orwell, a former bookstore clerk, complained about loiterers like me, who alight on bookshops simply because they are “one of the few places where you can hang about for a long time without spending any money.” The digital revolution has of course turned this charming vulnerability into a lethal one—witness the fate of Borders, Waldenbooks, B. Dalton, et al.—by converting the chain bookstore into little more than an air-conditioned showroom for Amazon.com.

In the United States, Barnes & Noble is one of the last of this dying breed, and it is in serious peril. This month, the company reported an abysmal second quarter with losses in excess of $25 million. Sales of its e-reader, the Nook, have collapsed and its stock has lost about 60 percent this year. Saddled with nearly $200 million in long-term debt, having spun off its somewhat profitable education unit and closed dozens of stores, B&N continues to wither. In an interview with the New York Times, Ron Boire, the company’s third chief executive in two years, suggested shifting the business away from reading toward things like games, gifts, and art supplies. He seemed particularly excited about 3-D printing and those oxymoronic “adult coloring books,” which Boire said capitalized on a new vogue among consumers for “physical interaction with things.”

While Barnes & Noble devolves from a bookstore into a thing store, Waterstones, the biggest bookstore chain in Britain, is plotting an entirely different course. In 2011, the company—choked with debt and facing the same existential threat from Amazon and e-books as B&N—nearly declared bankruptcy. Today, however, Waterstones isn’t closing shops but opening a raft of them, both big-box (in suburban shopping centers) and pint-size (in train stations). It has accomplished a stunning turnaround under the leadership of its managing director, James Daunt, who just announced Waterstones’ first annual profit since the financial crisis. How he pulled that off is a long story, involving old-fashioned business cunning, the largesse of a mysterious Russian oligarch, and some unexpected faith in the instincts of his booksellers.

* * *

The Waterstones flagship in London’s West End might be the largest bookstore in Europe. It’s got a whiff of intrigue about it; the basement café was once a frequent meeting place of MI5 agents, one of whom had a tête-à-tête there with Alexander Litvinenko the day before the Russian dissident was poisoned by polonium. I visited in high summer and didn’t even need to enter the shop to realize it was busy reinventing what a chain bookstore should look like. An entire window display, half a block wide along Piccadilly, was devoted not to the latest crop of beach reads and best-sellers but to one title, a classic, Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, copies of which were strewn about along with a suggestively toppled-over beach umbrella. A long quotation from the book was posted overhead that began: “A strange melancholy pervades me …”

Daunt is a bookseller by trade and inclination, not a retail executive like B&N’s Boire (whose résumé includes stops at Sears and Toys R Us). Sharply dressed, soft-spoken, Cambridge-educated, Daunt had a brief career in high finance at JPMorgan, but he quit at the urging of his wife, who didn’t want to be married to a banker, and decided, in 1990, to open an independent bookshop on Marylebone High Street. He was just 26. “I was a child,” he said over coffee in the Waterstones café. “I went around with the begging bowl. It was a primitive version of crowdfunding.”

The original Daunt Books—dusty, highbrow, a bit posh—has given rise to six other locations. All are honey traps for armchair travelers, with titles arranged not by subject or author but by country. The chainlet has always been prosperous, growing sales each year despite the financial crisis and the rise of digital, which have caused a quarter of the indie bookshops in Britain and Ireland to disappear over the past five years.

While Daunt weathered this difficult market, by 2010, he had grown very concerned about what lay ahead. He knew, for instance, that if all chain bookstores collapsed, many of the small- and medium-size publishers that filled his shop and supported the authors he loved—presses like Eland, which specializes in travel writing—would also fold. “A publisher of the Eland sort will sell typically 60 percent to Waterstones, 20 percent to Amazon, and 20 percent to the indies and the rest. You cut Waterstones out, and they go bust,” Daunt said. “So I didn’t want my supply—the talent, the nurturing, the world I’m in—to just get severely buggered around.”

But saving Waterstones’ 280 stores seemed practically impossible. The company was £170 million (about $260 million) in debt and about to file for bankruptcy when, miraculously, it was rescued by the billionaire Alexander Mamut, a complicated, influential figure in Putin’s Russia who one British broadsheet dubbed “the most powerful oligarch you have never heard of.” Mamut had been talking to Daunt before the sale and immediately brought him aboard to right the ship. “He wanted to make a mark in the United Kingdom, where he had a house, educated his son, and this seemed a positive, beneficial thing worth saving,” Daunt said of Waterstones’ benefactor. “Other people buy football clubs, fund art galleries—this was his thing.”

Once at Waterstones, Daunt tore up the business plan. His first target was the so-called planogram, a kind of map that tells chain booksellers which new books go where, ensuring that each store assigns exactly the same prominence to exactly the same titles. The very best locations in the store are actually sold to publishers. This includes the so-called best-seller list, whose rankings are determined not by the popularity of a given book but by how much a publisher is willing to invest to promote it. (A similar policy of “bookstore baksheesh,” as one editor dubbed it, seems to exist at B&N.) In 2011, Waterstones earned around £30 million just for this kind of advertising, Daunt said. Considering that the company was hemorrhaging money when Daunt took it over, forfeiting this revenue stream seemed crazy, and it also offended many publishers. “By giving control back to the booksellers, we were telling the publishers, ‘We know what sells better than you.’ That’s never a pleasant message,” said Daunt. “There was extreme nervousness. But we had the advantage of being bankrupt. Crucially for us, Penguin said, ‘Sounds mad. But what are the options? So we’ll support you.’ ”

By freeing up the placement of books, Daunt was able to optimize the selection for each store based on the type of customers coming in. What sold in working-class Gateshead wasn’t the same thing that sold in affluent Kensington. In some stores, he would discount. In others, he wouldn’t. “This is sort of difficult for booksellers to get their heads around, but some of the customers actually don’t want a discount. There is a fair price for a book, I think,” he says, picking up a doorstop history by the likes of Ian Kershaw. “You’re investing a lot more than 25 quid in this. For most readers, that will probably take a good month of your life. Almost the least important thing is how much it costs.”

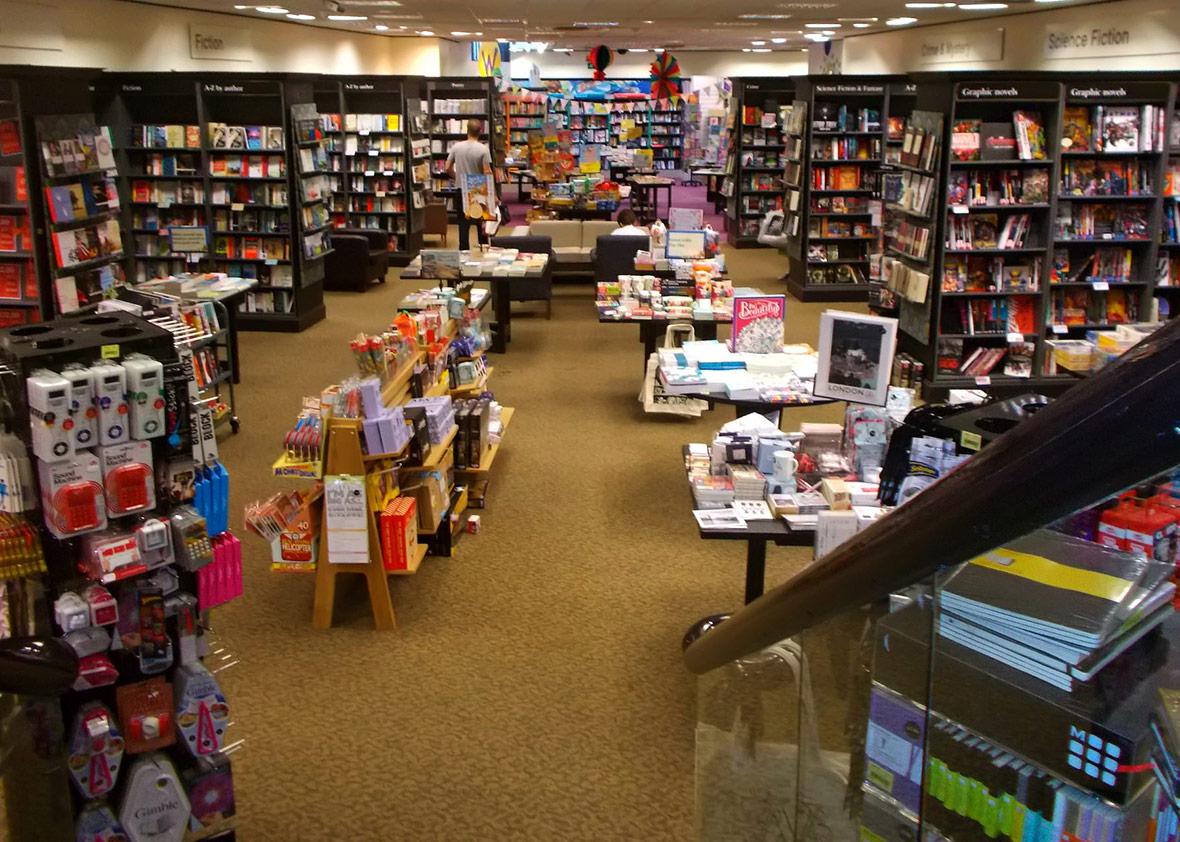

Photo by Tony Monblat/Flickr

Next came the staff. Daunt shrunk Waterstones’ central office and fired half of the store managers. He gave those booksellers who remained almost complete autonomy over how to arrange their stores—from the windows to the signage to the display tables—but controlled the stock with a dictatorial zeal. Out went books you wouldn’t want to browse: reference, technical guides, legal textbooks. That—along with the real estate freed up by eliminating publisher-sponsored placements—allowed Daunt to grow the total number of titles in stores by about a quarter. With more books to browse, sales increased. The number of unsold books that were returned to publishers fell from about 20 percent before Daunt took over to just 4 percent today.

A leaner staff and more autonomy resulted in everyone working harder, but Daunt says the staff is curiously happier as a result. “You love being in a shop where people are busy,” he says. “It’s much better than being out the back, filling up boxes of returns and thinking your life is a drudgery of doing pointless administrative tasks for some nameless bureaucracy of a head office who you despise because they just dump innumerable amounts of crap books on you.” As is probably clear, Daunt still has an indie bookseller’s contempt for the big chains, even though he now runs one of them. Of Barnes & Noble, which appears more and more like a cross between an airport gift shop and a toy store, he said, “My faculties just shut down when I go in there.”

For a CEO, Daunt is refreshingly impolitic. He has called Amazon a “ruthless money-making devil” and has relished the recent resurgence of print and the plateauing of e-books. He stocked Kindles in his store up until earlier this year, when he pulled them, gleefully, citing “pitiful” sales. The revival of print, and of Waterstones, confirms in a way Daunt’s worldview. “Do not underestimate the pleasures of reading,” he said last year. “The satisfactions of the book, in the age of social media and proliferating cultural choices, are very singular.”

If Daunt has created an economically sustainable model for the chain bookstore in the Amazon age, he’s done it in large part by not having a model: Each Waterstones looks different and sells different books depending on the local audience and the business impulses of the shop’s staff. In a way, Daunt has reanimated the lifeless body of the chain bookstore by infecting it, just a little bit, with the usually profit-proof sensibilities of an indie. While there may be lessons to learn in his success, it’s hard to imagine Barnes & Noble—which has twice the number of stores as Waterstones—precisely replicating it.

I’m pulling for B&N in any case. I wish Ron Boire the best of luck with his coloring books, scented candles, and anything else that can keep America’s last great network of bookstores in business. I don’t want to imagine what my own adolescence would’ve looked like without a big, safe space to read and to think and to drink peach Snapple while sitting in vinyl armchairs. If I didn’t have that space, I might’ve drifted toward someplace a lot less welcoming, someplace where there are no beverages. Like the library.