Of all the tricks in Uber’s playbook, the calculated tantrum might be the finest. For evidence of this, turn to San Antonio, where this week the ride-hailing company is celebrating a triumphant return after months of suspended service—not to mention a display of hell-no so effective it would make Ted Cruz jealous.

Uber stormed out of San Antonio on April 1, shortly after its first anniversary there. Prolonged negotiations with city regulators had failed to produce the precise operating agreement that Uber was seeking, and the company was having none of it. “City officials have created a regulatory climate that makes it impossible for us to meet the high standard of service that riders from over 170 cities across the U.S. have come to expect,” Uber wrote in a blog post announcing its departure on March 31. With its exit, Uber claimed, thousands of San Antonio drivers were losing “the opportunity to make a great living.” The company encouraged residents to “make your voice heard” and urge officials to reconsider their proposals. “Make no mistake,” the company declared, “we are not giving up on San Antonio, and will work hard to bring Uber back.”

A little more than six months later, Uber has made good on that promise. It inked a deal with the city on Tuesday that took effect immediately, and which both sides are heralding as a win. “We are excited to welcome Uber, a company facilitating more than one million safe rides a day, back to town,” San Antonio Mayor Ivy Taylor says in a press release. Uber will “work with the City” to recruit 2,000 new drivers to its platform. “We are glad to welcome back Uber to San Antonio in the spirit of collaboration,” adds Roberto Treviño, a city councilman. At the bottom of the release is a link to a copy of the signed agreement. Uber, in the spirit of collaboration we’ve come to expect from the company, got just about everything it wanted.

Rewind to February, ahead of a City Council vote on ride-hailing regulations scheduled for early March, when discussions between Uber and San Antonio were intensifying. Back in December 2014, Uber had threatened that if city legislators moved forward with certain regulations scheduled to take effect March 1, it would “likely result in Uber closing their operations” in the area. From the city’s perspective, the demand for Uber’s services and desire to keep it around were clear. San Antonio has a robust bus system but a sprawling footprint, and after roughly 12 months on the ground Uber was already handling tens of thousands of rides a month. But multiple sticking points remained.

San Antonio wanted Uber drivers to submit to fingerprinting and random drug tests. Uber felt those requirements were too burdensome and would deter people from signing up to drive on the platform. San Antonio had already made concessions on several other issues—agreeing to most of what Uber laid out on insurance policies and driver permitting—but on fingerprinting and drug testing, local officials were unwilling to budge. The two parties were also haggling over money. San Antonio had originally penciled in a fee structure similar to the ones for taxi and limousine services: $15 for a driver permit, $15 to renew a driver permit, $28 for reinspection, and so on. Uber felt strongly that its drivers shouldn’t have to pay fees.

Through a public-records request, Slate obtained documents and emails from Uber’s negotiations with San Antonio city officials in the months leading up to and through the March 5 City Council vote. The records offer a glimpse into how Uber, a company accustomed to steamrolling local governments, plays its brash brand of politics—in this case, privately working with San Antonio legislators and regulators on a compromise while publicly blasting the threat of regulation.

On Feb. 8, members of Uber’s policy team, a local lobbyist, and Uber San Antonio general manager Henry Carr strategized over email about meetings with city officials that week. (Frank Burney, a San Antonio–based lawyer who is also registered in the city as a lobbyist, forwarded the email chain, apparently by accident, to a San Antonio official.) “Would be great to get in front of [city councilman Joe] Krier as well, given his recent quote: ‘They are not walking away from the seventh-largest city in America,’ ” Carr wrote. “It might even be worth a 10 minute convo with [city councilman Mike] Gallagher. Probably a long shot, but I think he needs to hear from our mouths that we are not bluffing and we are prepared to leave.”

On Thursday, Feb. 12, Carr emailed multiple City Council members, Burney, and an attorney on City Council staff a synopsis of what Uber saw as “the most problematic aspects of the ordinance” from December. “As you will see, the issues are numerous and not easy to solve,” he wrote. Properly regulating Uber-like services “requires appreciating that a paradigm shift has occurred in the for-hire vehicle sector.” With March 1 fast approaching, Carr suggested San Antonio pass temporary regulations based on those in Austin, Texas—a city held up by Uber as a forward-thinking example—and work on a permanent agreement in the interim.

More emails went back and forth over the next week; then, on Friday, Feb. 20, Uber introduced its lawyer, Steve Siger, to the discussions. Later that weekend, Siger sent along a marked-up version of the San Antonio–Uber operating ordinance. “I wanted to reiterate our appreciation for your continuing to engage in these confidential discussions with us—we remain hopeful that we will find a path forward that keeps Uber in San Antonio,” Siger wrote to deputy city manager Erik Walsh. In the markup, two spots are flagged as “placeholders” to discuss fingerprinting and drug testing. That week, Siger flew into San Antonio to hammer out final changes with James Kopp, a city attorney. They met on Tuesday, Feb. 24, at San Antonio Police Department headquarters. Correspondence continued over the next two days and Treviño, the lead councilmember working on the effort, says he felt hopeful they were making progress.

Late Thursday night, with the City Council vote one week away, Uber’s public policy lead Adam Blinick sent a lengthy email to Walsh. “I wanted to share with you some thoughts, understanding where you guys are in the process,” Blinick wrote. “I understand that the City is unwilling to move on requiring random drug testing and fingerprinting of all drivers in its recommendations to council. I’m unable to say with certainty whether Uber will continue to operate in San Antonio. However, if fingerprinting and drug testing are to be included in the ordinance, also including the following items will maximize the likelihood that Uber continues to operate.”

Blinick went on to lay out four key concessions that Uber required of San Antonio. First on the list was that any fingerprinting and drug testing provisions “should explicitly be made a pilot program by having them sunset at the end of 2015.” Uber also wanted drivers to have a 45-day grace period for scheduling their fingerprints, to limit the city’s access to driver records, and to ensure that “records obtained by the City from a [transportation network company] or TNC driver should be treated as though they are proprietary for the purposes of the Texas Public Information Act, regardless of where the records are clearly marked as such.” Blinick suggested they speak “first thing” Friday.

On Tuesday, March 3, Blinick flew into San Antonio and Walsh agreed to “pull everyone” together for a last-minute meeting. In the final version of the agreement, submitted in advance of the City Council meeting, the two sides appeared to reach a compromise. On fees, Uber would pay a flat fee of $25,000, which would cover half of the city’s estimated administrative costs for setting up and accommodating ride hailing. (Uber competitor Lyft, which was engaged in simultaneous negotiations with San Antonio on many of the same points, would pay the other half.) The city struck pre-employment drug tests for drivers, a requirement of the December ordinance, from the terms in favor of randomly drug-testing 10 percent of them over the course of a year. Drivers would also be given a 14-day grace period to get fingerprinted. The full process was scheduled to be reviewed in September 2015, after the conclusion of the 2015 session of the Texas Legislature, which was considering state-level changes on ride hailing.

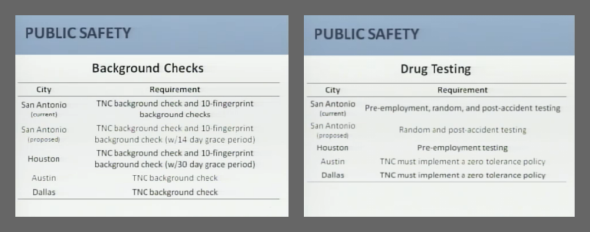

Slides from the San Antonio City Council meeting on March 5

“We felt great because it was collaborative,” Treviño told me in April. “We worked with their lobbyist, their people. I wanted it to be very collaborative and stay very positive.” Then, on the eve of the vote, Uber released the following statement to the press:

Drivers and riders in San Antonio were hopeful when they learned Mayor Taylor would delay implementation of the redundant requirements and lead the charge to create modern regulations for ride-sharing in San Antonio. However this hope was short-lived as the City Council’s revised ordinance still includes many of the same duplicative and unworkable driver requirements. The anti-competitive provisions of the ordinance remain intact—many of them requiring drivers to spend time and money jumping through municipal hoops to achieve objectives already accomplished by the Uber platform.

The regulations adopted in December extend far beyond anything we’ve seen in the state. By the mayor’s own admission, many of these requirements are not “feasible.” Even with the proposed changes, this regulatory framework remains one of the most burdensome in the nation and stymies our ability to operate in San Antonio. This is why we asked the city to repeal the entire ordinance and replace it with smart regulations similar to those adopted by nearly two dozen other jurisdictions, including Austin. Without a full repeal, we will be forced to leave town.

Treviño was shocked. “They didn’t bother to contact me, they didn’t bother to contact staff or city management—they just went straight to the city paper and they said we’re going to pull out, this is too onerous,” he says. “It surprised all of us that they had an article in the paper saying the language was onerous and they were against it. When I came in for council everyone’s looking at me like what the hell? What’s wrong with you?”

Asked this week about this characterization of events, Uber declined to comment on the record. Carr did not respond to multiple email requests for comment. Reached by phone, Burney deferred comment to Uber’s communications team.

On Thursday, March 5, the day of the City Council hearing, Walsh took the podium to present on the proposed amendments to San Antonio’s December ride-hailing ordinance as planned. He emphasized that the city’s top concern was public safety, “and that, in that role of ensuring public safety, the balance is really upon us to make sure that we don’t overregulate and that we help facilitate any business.” Walsh described how officials had decided to loosen the ordinance’s fingerprinting requirements and to eliminate pre-employment drug testing for drivers. “We think this is a fair compromise in terms of meeting the needs that the TNC has talked to us about regarding barriers to getting their folks on board,” Walsh said.

The City Council passed the amendments, 8–2. And Uber walked.

During the months following that blowout, Uber did what it does best—agitating for a revision of the regulations that had “forced” it to depart and riling up the public along the way. In San Antonio, Uber found support from more than 14,000 people who signed an online petition, as well as Tech Bloc, a pro-technology advocacy group that organized multiple rallies in favor of bringing ride hailing back to the city. Brad Parscale, a San Antonio resident and Tech Bloc co-founder, eventually helped broker the deal between Uber and the city that took effect this week. “At first it seemed like there were people at the city angry, and it seemed like Uber was pretty distressed that things didn’t go well,” Parscale says. “There was this tendency that the city just thought that Uber was cocky and didn’t really care. I didn’t get that at all, honestly. Everyone I met at Uber is, like, super great and nice.”

Parscale thinks San Antonio miscalculated in its first go-round with Uber by acting as though “we were the center of the universe.” The nine-month pilot agreement signed Tuesday suggests no such assumption. It does not require drug testing for drivers, nor does it say anything about fingerprinting. (Treviño says the parties reached a sort-of compromise on the latter—drivers can elect to get fingerprinted, which will earn them a special certification from the San Antonio Police Department on their Uber profiles.) The agreement also doesn’t include any driver-specific fees, though Uber will pay the city a prorated operating fee of $18,750 to cover those nine months. All in all, the terms look almost exactly like what Uber wanted, and very little like what San Antonio originally proposed.

“I think a lot of people come and beg cities for their business,” Parscale says. “Uber is a big company and it’s a moving technology and, honestly? It was up to our city to beg for them to be here. We need that kind of technology.”

With people like Parscale issuing such pleas, it’s no wonder Uber feels entitled to strong-arm local regulators and affect hysterics in cities across America. Uber has sold profit-minded investors on its business to the tune of more than $8 billion in backing, but it’s also sold real people on the idea that their cities need Uber, something that’s a lot harder to put a price on. Uber has run the San Antonio play or a version of it in plenty of other cities before, including Boise, Idaho; Las Vegas; and Portland, Oregon. Surely it will do so in others going forward, questioning the authority that local regulators have to weigh new technologies that could very well fill big gaps in their transportation networks. From the company’s perspective, why shouldn’t it? Within half a year in San Antonio, Uber had finagled the accord it wanted from the start and all was forgotten. “At the end,” Parscale says, “everybody was smiling.”