In mid-June, Amanda Hite, president and chief operating officer of Smith Travel Research, delivered some exciting news at an annual hospitality conference in New York: U.S. hotels were killing it. For the 12 months ending in April, hoteliers had hit all-time highs in occupancy, average daily room rates, and the money made off each room. Over the next two years, more growth was expected. This marked a stunning return from the recession, which left the lodging industry battered as businesses and households alike slashed travel budgets. “We continue to experience some of the best fundamentals that we’ve had,” Hite said.

Hotels aren’t the only players in hospitality enjoying a banner year. Late last month Airbnb, the popular alternative lodging site and poster child for the “sharing economy,” closed a $1.5 billion funding round at a towering $25.5 billion valuation. One of the biggest privates rounds ever, the new money vaulted Airbnb into the upper echelons of the ultra-elite club of billion-dollar startups. Only two other venture-backed private companies—Uber and Chinese electronics-maker Xiaomi—have valuations that are greater. Airbnb, which helps people rent out their homes and spare rooms for short stays, is expected to top $900 million in revenue this year. By 2020, that figure is projected to increase more than tenfold to $10 billion. Airbnb’s listings and annual guests have soared as well, roughly tripling from 2013 to 2014.

That astounding growth is just the latest sign that Airbnb is making good on its promise to “challenge the status quo,” as co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky once put it. Here and now, Airbnb isn’t profitable, forecasting an operating loss of about $150 million for 2015. But at $25.2 billion, Airbnb’s valuation has already surpassed the market cap of major hotel chains like Marriott ($20.6 billion), Starwood ($14.1 billion), and Wyndham ($10 billion), and it’s close to eclipsing that of Hilton ($27.4 billion) as well. While Chesky has at times balked at the term disruption, numbers like those can’t be denied. Airbnb is disrupting hotels. Which is why it’s so surprising that midway through 2015, somehow, both Airbnb and hotels are thriving.

To start to understand why, first look back to 2009, as the aftershocks of the financial crisis were sinking the U.S. deeper into recession. Lending froze. Housing starts plunged. And in the hotel industry, the well all but dried up. “Everybody and their brother got their teeth kicked in,” says Jan Freitag, senior vice president of STR, the hotel industry research firm. “Banks wouldn’t lend anything for anything, but especially something with a one-night lease.”

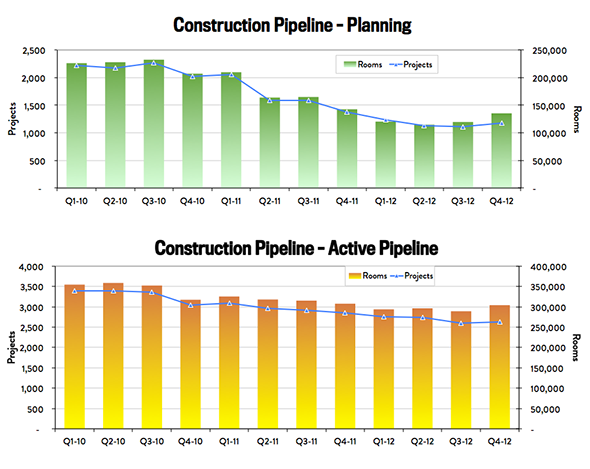

Development of new hotels and hotel rooms slowed dramatically. From the first quarter of 2010 to the second quarter of 2011, the number of hotel rooms under construction plunged 33 percent, from more than 75,000 to just over 50,000. The overall “active pipeline” of projects—which ranges from plans with initial approval to those currently under construction—declined more or less steadily from early 2010 until late 2012, according to data from STR.

Charts courtesy of STR.

Only now, three years down the road, is the hotel supply pipeline starting to flow again, encouraged by industrywide reports of record room rates and occupancy. “People are starting to build,” Freitag says. “What we’re seeing right now is the number of rooms under construction is up 21 percent. The pipeline is heating up, but we’re not seeing that in the supply numbers because it takes so long.”

In other words, some of the hotel industry’s current good fortune can be explained by basic supply and demand. For a long time, the supply of hotel rooms was low, and it’s since rebounded much more slowly than demand for hotel rooms. So occupancy, and room rates, and the revenue made off each room, have gone up. What’s confusing is how hotels and Airbnb have managed to ride seemingly concurrent waves of demand without experiencing any destructive interference.

The most common explanation offered for this is that Airbnb and hotels serve fundamentally different markets. Airbnb, industry experts argue, is for the casual leisure traveler. The supply is less predictable, since it depends on the availability of each individual host, as are the specific amenities. Airbnb might be ideal for a family or group of friends vacationing in Europe, but it’s less well-suited for the McKinsey consultant who travels to Toronto each week and needs reliable accommodations. “So for leisure travelers, transient segments, Airbnb’s probably a pretty scary threat,” says Cathy Enz, a professor at Cornell’s School of Hotel Administration. “But there’s still meetings, there’s still conventions, there’s still groups of people. Typically that’s kind of a lower, corporate-negotiated rate, but that business clearly isn’t Airbnb’s.”

There’s evidence to support that statement. STR examined hotel occupancies in Austin, Texas, during the South by Southwest festival, in Louisville during the Kentucky Derby, and in Omaha, Nebraska, during the Berkshire Hathaway’s 2015 meeting. And as far as it could tell, people were still staying in hotels as much as ever, “despite the fact that the organizers of those events were actively promoting Airbnb,” Freitag says. On top of that, consider that San Francisco, the city where Airbnb was founded and remains headquartered, was one of the top-five-performing markets for hotels in 2014, with 84.1 percent occupancy and room rates that increased 10.9 percent. “Is there Airbnb activity in San Francisco? Yes,” Freitag says. “Does it have an impact? Maybe, but it’s really hard to tell.”

Airbnb, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment over several weeks, has done its best to propagate the idea that it doesn’t really compete with, but rather complements, the stalwarts of the hospitality industry. The company, in various economic studies, has found that roughly 70 percent to 80 percent of its listings are located outside a city’s central hotel and tourist district. Presumably it’s in Airbnb’s interest to keep up that impression as long as possible—the less hotels see it as threatening, the less opposition and regulatory scrutiny it’s likely to encounter.

That said, $25.5 billion ambitions aren’t so easily cloaked, nor does all the data support Airbnb having a negligible effect on hotels. A paper from researchers at Boston University found a “statistically significant decrease in occupancy rate and an even bigger decrease in hotel room prices” from Airbnb in Texas. In a sign that hotels don’t plan to be complacent, the Financial Times reported late last month that Hyatt had taken a stake in Onefinestay, a British company and upscale Airbnb competitor, and Wyndham had invested in subscription home-swapping site Love Home Swap. On the opposite side of that, Airbnb last year partnered with Concur, an expense management company, and has been working to improve its business travel program.

So maybe hotels are slowly trying to integrate more Airbnb-like services into their holdings, and Airbnb is steadily trying to become slightly more hotel-like in its offerings. “They’re bound to get more similar over time from both sides,” says Arun Sundararajan, professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business. Right now, though, Airbnb and traditional hotels are still far enough apart that not only have they avoided a collision, they’re both managing to thrive. In fact, it’s even possible that the popularity and hype around Airbnb have helped hotels a bit, simply by driving new interest to the market for short-term accommodations. Midway through 2015, the hospitality pie is growing for everyone. But for hoteliers, there’s also a looming, not-so-distant future in which $10 billion of that pie belongs to Airbnb—and that’s bound to look pretty scary.