Parmanand Bipat had driven for Uber in New York City for about four months when he decided to try out night work. It was a cold January evening, in the single digits, as he headed over to an Upper East Side address to collect a fare. When he arrived, he saw a man already standing outside, looking anxious. “My wife’s inside going into labor,” the man said. “I’ve got to get to the hospital.”

“Sure, no problem,” Bipat replied, waiting as the man’s wife exited the building. She clambered into the back of Bipat’s SUV, breathing heavily. The couple was heading to a hospital all the way across town; Bipat continued north and paused at a traffic light. That’s when he heard the scream.

“Oh my god, Bill, the baby’s coming!”

“He says to her, ‘OK, honey, we’ll be at the hospital soon,’ and she’s like, ‘No, it’s coming! It’s coming!’ ” Bipat recalls. “I’m getting nervous now, and I think, ‘OK, maybe I should pull over or something.’ And then he says, ‘The baby’s coming! Do you mind calling 911?’ So I get on my speakerphone in the car and I call 911.”

Bipat pulled over and was still on the phone with 911 when an ambulance came blaring down the street. Jumping out of his car and running into the street, Bipat waved his arms frantically to flag down the ambulance. “This woman is having a baby in my car, right here, right now!” he told the driver. Together, he and the EMT raced back to the Uber—where they found that the baby had already arrived in the back seat.

Courtesy of Uber

In the age of the so-called “sharing economy,” giving birth in an Uber or a Lyft is the modern iteration of the fabled taxi birth. But unlike professional cab drivers who are well-versed in dealing with all sorts of passengers and situations, the people driving for car-service startups aren’t necessarily pros and likely haven’t been on the job all that long—certainly not long enough to consider the possibility that they might start a fare with one passenger and end it with two.

Monica Azhar, a driver for Lyft in the Los Angeles area, couldn’t clearly see the woman who climbed into the back of her car at 2 a.m. this past May, but noticed her heavy breathing. Azhar asked if the woman was in labor, then tried to occupy her with small talk as they headed toward the hospital. “I’ve been a social worker for 7½ years, so I put that hat on really quickly,” Azhar says. “I felt like she got a little more comfortable because she started screaming louder. At first she was trying to hold it in, and I was like, ‘No, no, just let it out, it’s OK.’ ”

When the pair arrived at the hospital some 10 minutes later, Azhar leapt out of the car and dashed in to get a wheelchair. “I wheeled her in running—it was the funniest thing, because I don’t run, I just don’t do it—I was running through this hospital, and I was like, ‘This woman is having a baby!’ ” Azhar recalls. “I threw my keys to the security guy, and then another security guy said, ‘Let’s go,’ and he ran with me to the proper area.” Azhar identified herself as a friend, offered to stay until a family member arrived, and left a cellphone number. An hour later, a text came saying the baby had been born.

“It’s kind of indescribable: We’re strangers, and the second we meet I’m a part of this life that’s coming through,” Azhar says. “I think Lyft has done a great job with their whole mantra of ‘a friend with a car,’ building that sense of community, so I wasn’t nervous. My only focus was making sure she was comfortable.”

Photo by Josh Mohrer

That promise of community—of “sharing” a ride with a real person who’s just picking up some extra cash on the side, rather than with an aloof professional—might be one reason for someone in semiurgent need to book a Lyft or an Uber instead of hailing a cab or even calling an ambulance. Another reason is reliability. On Lyft’s and Uber’s high-tech platforms, a would-be rider can order service from her home and get a fairly accurate estimate of how long it will take for the car to arrive, rather than trying to hail down a cab in inclement weather with a baby knocking at her door. In what Conan O’Brien called “the best ad for Uber ever,” actress Jaime King told the talk show host in August that she took an Uber to the hospital to give birth while her husband was off filming a movie. “I thought an ambulance would be very dramatic,” King said. “And I know that they’re like, they say three minutes away, and [with] an ambulance you don’t know. So I can rely on Uber.”

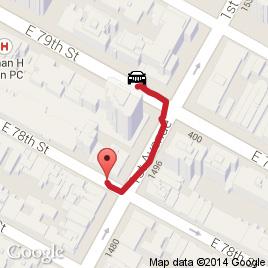

Ordering an Uber or Lyft through an app can also prevent other unmetered car services from taking advantage of women in labor. In a February Planet Money episode, NPR’s Jacob Goldstein described the ride he and his wife took from midtown Manhattan the Friday afternoon his second daughter was born. “Finally a guy in a black town car pulls over, and the good news is we’re just like 10 blocks from the hospital.” The bad news? “We get in the car, we start going, the guy says, ‘It’s going to be $25.’ ” Sure, Uber’s price-surging practices are controversial, but at least they’re not singling out desperate individuals.

If a woman starts to deliver along the way, what should a driver do? Spreading out an unopened newspaper to create a sterile surface is a “common myth,” according to Raymond Sandler, director of labor and delivery at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City (“Nothing is sterile in terms of no bacteria anywhere”), but in a pinch it’s better than an obviously dirty surface and will absorb some of the afterbirth. (Bipat remembers getting odd looks when he showed up to have his blood- and fluid-stained SUV detailed.) Eileen Ehudin Beard, a certified nurse-midwife and senior practice adviser at the American College of Nurse-Midwives, says the most important thing post-birth is to keep the newborn warm, which is best achieved by the mother pulling the baby to her chest.

Medical professionals note that having someone actually deliver en route to the hospital is extremely uncommon. Sandler says that the first thing a woman going into labor should do is call her physician to go over signs and symptoms to assess how fast the baby is arriving, then pick the best way of getting to the hospital. “Very few deliver along the way,” says Ehudin Beard.

Then again, you never know. Sandler, who’s been in practice for 40 years, said when it came time for the wife of a physician on his staff to give birth, the doctor examined her and decided that they had time to make the 40-minute drive to Manhattan. As they drove onto the Triborough Bridge, she broke her water. The hospital was 10 minutes away; he pulled over and delivered the baby in the car. Uber or Lyft probably wouldn’t have been any faster—but at least someone else would have cleaned up the mess.