Last August, Amazon flew about 80 writers on its Thomas & Mercer mystery and thriller imprint—including me—to Seattle for a conference. They put us up at the Westin downtown, a nice hotel by any standard, and spent the weekend feeding us well and serving us top-shelf booze at an increasingly fabulous series of parties. There were tourist outings, the usual conference mix of panels and workshops, and a non-stressful visit to the Amazon Death Star. Also, they gave us a free Kindle Paperwhite, a nice touch.

With a few exceptions, none of the writers at the conference were particularly famous; some had only published one or two books, all with Amazon. The Seattle trip wasn’t normal treatment for them, or for anyone. I’ve published books with independents and with big corporate imprints, and I’ve published books on my own. Each of these experiences was positive in its own way. But never before had I been treated quite like this. It felt like I’d entered a glorious new age. Amazon had given me a free sneak preview of what book culture would be like from now on.

As usual, I was naive.

A year later, Amazon is embroiled in an ongoing dispute with the Hachette publishing company over e-book pricing, in which Amazon has delayed shipments and removed discounts and pre-order buttons from Hachette titles. This is a literary feud unparalleled in vitriol since Gore Vidal compared Norman Mailer to Charles Manson. One evening, I turned on The Colbert Report to find Hachette author Stephen Colbert sticking his arms up through an Amazon box, middle fingers extended. On Twitter, Colbert urged his viewers to #burndowntheamazon. Meanwhile, 900 writers, many of whom I respect greatly and some of whom I know personally, signed a letter under the name “Authors United”—apparently united by novelist Douglas Preston. They argued that Amazon was establishing some sort of corporate crossfire zone, with best-selling authors as the innocent villagers, the collateral damage. This statement appeared in that last refuge of the literary underdog, the New York Times. It read, in part, “we encourage Amazon in the strongest possible terms to stop harming the livelihood of the authors on whom it has built its business.”

The Times has been running several negative articles about Amazon a month, usually by David Streitfeld, grinding the sharpest ax since Snow White’s Huntsman. Salon seems to publish a Laura Miller anti-Amazon screed every hour. Meanwhile, Bookpeople, the excellent independent bookstore in my hometown that had been so important to starting my own writing career, refuses to carry my Amazon-published books. My Facebook feed is a morass of authors, known and unknown, linking to anti-Amazon articles, comparing Amazon to the Nazis or to Pol Pot. When I waded into one conversation to say, “Hey, Amazon’s not so bad,” someone referred to me as being like “the Vichy French, taking money to cover up crimes.”

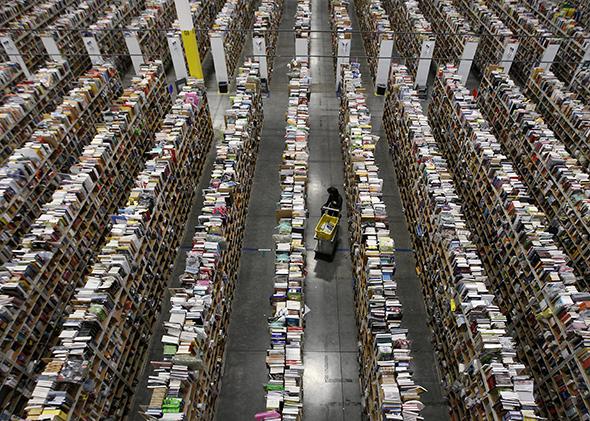

What in the name of Bezos is going on here? There are obviously a lot of issues at play: the consolidation of publishing, worries that reduced e-book prices will send royalties crashing to the floor, general tsuris that e-books are replacing paper books, distress over the working conditions in Amazon’s warehouses, and more. I don’t want to minimize anyone’s concerns about any of those things. But while everyone seems to hate Amazon, my personal experience with this supposedly evil corporate behemoth has been fantastic.

When Amazon picked me up off the slush pile in 2011, my decade-long, five-book career was effectively dead. I had a modest contract with a legacy publisher for a pseudo-self-help book, but I didn’t want to write it, they no longer wanted put it out, and I’m pretty certain nobody would have wanted to read it. My antiquated dream was to write novels, but my previous and only novel had sold so poorly that I wouldn’t have been able to give away the next one for free, to any publisher.

Instead, through Amazon, I’ve published three full-length novels—a historical action comedy set in the very specific world of 1930s Jewish basketball and two detective stories set in the L.A. yoga scene, originally written in serialized form—as well as three 10,000-word novellas, including an extended piece of Kurt Vonnegut “fan fiction,” all in the last 30 months. I have another novel, a time-travel romantic comedy, coming out next March and I’m under contract to write still another novel, subject yet to be determined. It’s been the most enjoyable creative burst of my career, a gleeful hack’s sprint toward nowhere in particular.

Amazon has supported my strange whims. Their formula for literary success is, as far as I can deduce: Write as many books as you can, and then sell them cheaply and in bulk. But that doesn’t mean making a shoddy product. The editing at Amazon Publishing—and I’ve worked with several different editors—has been as good as any I’ve ever received, as has the copy-editing and design. They’re willing to work at my pace, and always tell me that I can slow down my pace if I need to.

I haven’t gotten rich, but I haven’t dropped into poverty, either. Even though none of my books has sold more than 15,000-ish copies, Amazon continues to pay me to write them. The idea is that eventually one of my efforts will hit, and then the backlist will rise. The advances aren’t huge; they’ve all been in the low—and I do mean low—five figures. But that strikes me as exceedingly fair pay for mediocre-selling serialized novels about an L.A. yoga detective. It’s not enough money for me to stop doing other, nonfiction-writing work. But I don’t want to stop doing other work. What I do want is to get paid for writing fiction, and that’s happening. Amazon has allowed my novels to be part of the mix. If, someday, they become a bigger part of the mix, well, that’ll be a bonus.

It’s almost the exact opposite scenario as the one predicted in the ominous Authors United letter. My friend Deborah Reed, a wonderful writer but not a household name, has sold more than 100,000 copies of her novel Things We Set on Fire—virtually none of them in a conventional bookstore, since conventional bookstores won’t sell Amazon Publishing–produced novels. “Being able to reach hundreds of thousands of readers through Amazon’s database has allowed me to build a career and support myself, which is highly unusual for a writer,” she wrote in an email. “Rather than my books falling into obscurity after the initial launch, Amazon has the capability to keep the interest going by highlighting a book years after it was published.”

Other writers, by the hundreds, are coming out of even more obscure places. In April 2013, graphic designer Jason Gurley, who’d written and self-published three novels in the space of a year, met Hugh Howey, Amazon’s most successful author—so successful at self-publishing that he then got a huge deal from Simon & Schuster. Howey encouraged Gurley to write fan fiction based on his hyper-successful Wool series. Gurley’s fan fiction did well enough that he was able to persuade Amazon to publish an original novel, Eleanor, which has sold close to 10,000 copies since it came out in late June, at one point hitting No. 25 on the Amazon best-seller list. “It’s infinitely more than I’d hoped to sell,” Gurley told me, “and I’ve built a lot of really fantastic relationships with readers as a result.”

So when I hear people say Amazon is “destroying” literary careers, it just doesn’t make sense—it actually seems to be making them. But while I have trouble seeing my publisher as a villain, others don’t. I asked a couple of friends, both successful writers published by Hachette, to offer their perspective; they declined. However, my friend Emily Gould, not published by Hachette (her recent novel Friendship is from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) but always willing to wade into debates, offered this perspective:

The opportunities that Amazon has given authors who write genre fiction have been great, and that’s not inconsequential. But as a writer and publisher of what is unfortunately categorized as “literary fiction,” Amazon’s treatment of books like widgets does seem frightening. The recent statement they released about ebook pricing is a great example of what I’m talking about: they don’t seem to have a handle on what, to most readers and writers, is a self-evident fact: that some books are priceless and others are worthless. Ergo, saying that people who want book X but don’t want to pay price X will buy a cheaper book that’s sort of like book X instead ignores how readers actually think to an almost comical extent.

That argument reminds me of what a friend said after my novel Downward-Facing Death—a masterful title if ever there were one—racked up more than 100 reviews on Amazon, the first of my eight books to ever crest that golden number. “Yeah, but those are just Amazon readers,” my friend said, as though there were a difference between Amazon readers and non-Amazon ones. I treasure and respect every review, even if 20 of them are one-star takedowns because the readers couldn’t figure out how to download the book to the Kindle, the equivalent of my grandma asking me to program the DVR.

We need to give readers, even the senile ones, more credit. Book pricing doesn’t have anything to do with a book’s worth. It’s just a sales point. Novels by Gary Shtyengart or Jennifer Egan aren’t better than other novels because they’re expensive, and the modern equivalent of dime-store Westerns aren’t worse because they’re not. People like what they like, and they’re not going to like books any more or less because they cost more or less. I like good literature, and I also like cheap books. Maybe there’s a place where quality and a decent deal can meet, and then we can stop with these “whither the novel?” laments.

Amazon, like every publisher, releases a lot of genre pulp, much of which sells like lemonade in August. But just because a book is inexpensive doesn’t mean it’s bad. While I don’t think my books are worthless, I also don’t have a lot of delusions about how much they’re actually worth. If I can sell 10,000 books at $3.99 a download, which I’ve been consistently able to do through Amazon, that strikes me as a better deal than being able to sell 3,000 books at $12 a paperback, particularly because my royalty rates are way higher on downloads and I can jam out two or more of those downloadable books a year. It’s not a strategy that will work for every author, which is why legacy publishers will continue to thrive, or at least survive, and will continue to publish the bulk of “quality” books in this country. But for a proud Grub Streeter like me with only marginal pretenses toward literary finery, the Amazon system is a dream.

Meanwhile, I’ll get to work on my next project: two fan-fiction novellas in Amazon’s red-hot Kindle Worlds Romance category. Amazon ordered them because they thought I’d offer a funny take on the genre. I never thought I’d be a romance novelist, but why not? It sounds like fun.