As long as there is an Internet, stupid stunts will occasionally go viral. Remember planking? Icing? They flare up, they go away, little harm is done.

The Ice Bucket Challenge, however, is different, because it’s not going away. The challenge started in July, at least in its present incarnation, but it wasn’t until Aug. 13 that the ALS Association put out its first press release about the phenomenon. The charity tallied $5.7 million in donations in the two weeks between July 29 (when my friend John Carney took the challenge) and Aug. 13; it boasted that “everyone from Ethel Kennedy to Justin Timberlake” had participated.

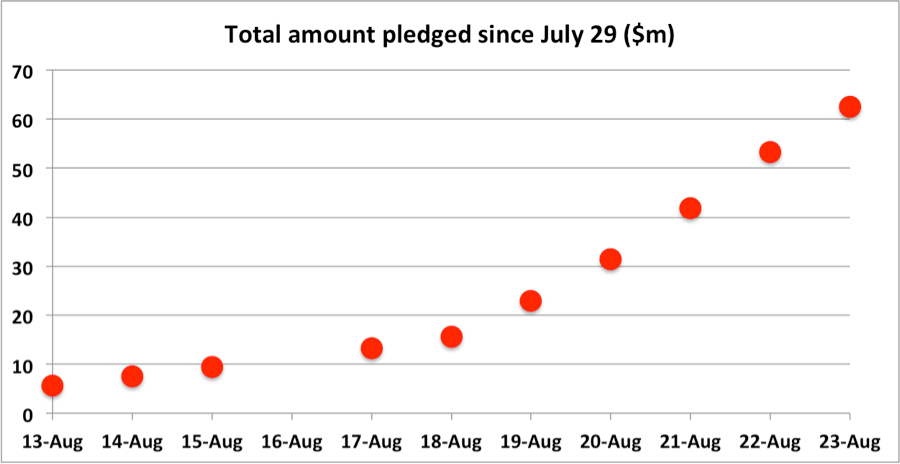

The next day, the total was up to $7.6 million: Some $1.9 million extra had been pledged in 24 hours. But the trend had barely gotten started. By Aug. 15, the total was $9.5 million, while by Aug. 22 it was $53.3 million, having increased by $11.5 million in one day. By Aug. 24 it had reached $70.2 million. Here’s a pretty chart for you that seems to indicate that we’re well on our way to reaching the $100 million mark:

Chart by Felix Salmon

Clearly this fad has outlasted just about all expectations. It’s almost as though it were invented in some kind of viral factory. (I count 41 BuzzFeed posts on the subject and rising.) It has celebrity and built-in virality (“tagging” friends) and wet T-shirts and humor (all those #fail videos)—and, crucially, it has a random Good Cause attached. Even if you think the whole fad is incredibly stupid and/or dangerous, it has become de rigueur to say that if you don’t want to pour ice water all over yourself, it’s still important to donate to ALS.

“Turning a pointless viral meme to noble ends can only be a good thing,” wrote Will Oremus in Slate, praising all the good that the money will do for “the 12,000 Americans who have the disease, and for their families and future generations.”

But giving money to a disease-specific charity is a very odd, and peculiarly ineffective, way of spending your philanthropic dollar—especially when your donation is a one-off thing. What is the ALS Association going to do with all this money? They haven’t said. The organization’s primary focus is scientific: They fund research into the disease and potential cures. ALS is a tough nut to crack, however: After 30 years of work, we don’t seem to be any closer to finding a cure. And there’s no particular reason to believe that we’re $100 million away from finally getting somewhere. Even if a million Americans donate $100 each to ALS, the net positive effect on the world might well be very small indeed.

Surely a substantial portion of the money being donated to ALS is genuinely additional: It represents money that Americans would not otherwise have given to charity at all, rather than just being a way of moving charitable donations from one recipient to another. Still, William MacAskill has an informed estimate that a good 50 percent of the money being given to ALS is ultimately coming out of the pockets of other charities. So it’s reasonable to ask: Are we better off in a world where the ALS Association has an extra $100 million and other charities have roughly $50 million less?

I fear that the answer might be no, we’re not. For one thing, medical research—especially early-stage medical research into a disease like ALS—is a very long-term undertaking. You need to fund scientists year in and year out; throwing a large grant at them in 2014 and then going away would probably end up causing more harm than good. As a result, most of this money will (and should) probably end up simply sitting on the ALS Association balance sheet, maybe earning some modest rate of interest, getting doled out very slowly over many years.

In terms of bang for the buck, then, giving money to the ALS Association is not much better than giving it to Harvard. Rather than being front-loaded and effective, it’s going to be back-loaded and (sadly, given the results of the $100 million that the ALS Association has spent to date) probably ineffective. Perhaps the ALS Association could endow a prize: $50 million for the first person to come up with a cure for the disease. But even that would probably do little good. People don’t embark upon major scientific research projects just on the off-chance that they might be first to a prize.

What’s more, those research projects still need to be funded while they’re happening, which brings me to my next point: that fundamental medical research should be coordinated sensibly, on a national level, by the NIH, or even at a global level. Having a grab-bag of disease-specific charities competing against each other for research talent is extremely unlikely to result in an optimal allocation of medical resources.

Meanwhile, there are thousands of charitable organizations out there that could really use the money going to ALS—could use it to make the world a better place today. Some are medicine-based, treating the sick around the world; others might be in areas such as education, or clean water, or animal rescue, or the arts, or simply just giving money to poor people. In virtually all these cases, there’s an obvious positive effect to any donation. Not all philanthropic activity should be obvious, of course, or require immediate positive effects. But the less good you’re going to do in the short term, the more good you should expect to achieve in the long term. And I don’t think the ALS Association quite gets there.

Of all the charities to have become a surprise beneficiary of a weird viral phenomenon, then, ALS is hardly the best and is in many ways one of the worst. For all the money being donated, an even bigger effect of the ice bucket challenge is “awareness”—and awareness of ALS does precious little good to anybody. Knowing about ALS won’t help anybody prevent it, for instance. On top of that, most of the money is not going to help people with the disease, because the ALS Association mainly spends its money on research.

If you think there’s something important to be done to help people suffering from neurodegenerative diseases, then wouldn’t it make sense to include the vastly greater number of people with, say, multiple sclerosis as well? ALS is so rare—the association estimates that 5,600 new cases are diagnosed in the U.S. each year—that it seems a bit odd as the focus of a major national philanthropic phenomenon. Giving a charity an unexpected windfall doesn’t always have wonderfully positive results. So maybe it’s time to stop giving to the ALS Association at this point. And start giving to a few other charities instead.