The recent Senate committee hearing on how General Motors dealt with its deadly ignition switch defect provides the latest glimpse into the crisis of inattention, deferral of responsibility, and lack of accountability that permeate America’s largest automaker. GM acknowledges, so far, that 13 people were killed as a result of more than a decade of institutional cover-up and negligence brought on by an imperious corporate culture. Clarence Ditlow, head of the well-regarded Center for Auto Safety, has predicted that the death toll will go into the hundreds.

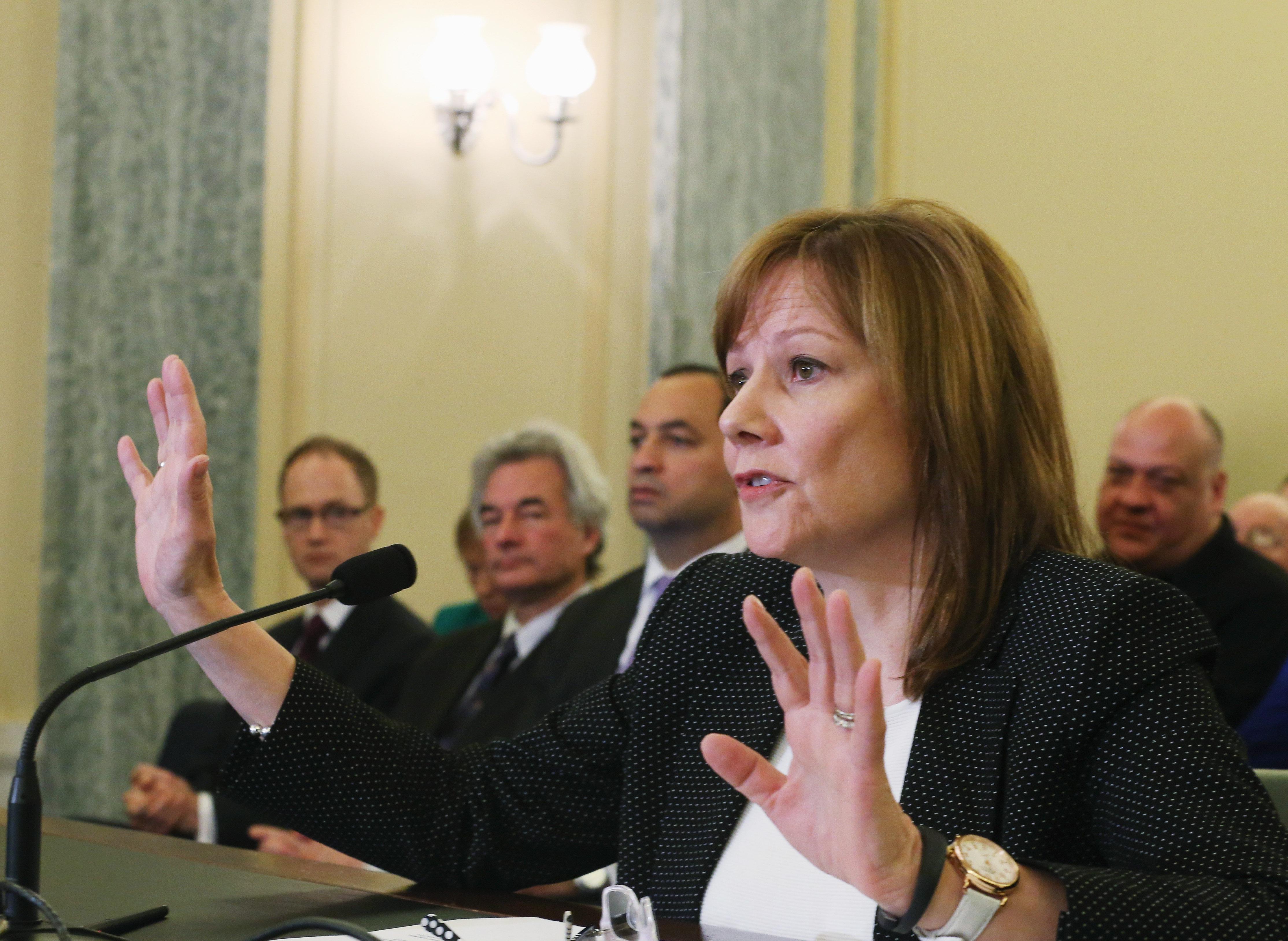

In the hearing, GM’s general counsel, Michael P. Millikin, came under criticism for his failure to act and—in the words of subcommittee Chairwoman Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.)—for his “Whac-a-Mole” approach to ignition switch–related lawsuits, even though engineers at GM were aware of the defect. McCaskill twice questioned whether Millikin should still have his job and why CEO Mary Barra has not fired him. Barra defended Millikin, who himself testified, “We had lawyers at GM who didn’t do their jobs, didn’t do what was expected of them. Those lawyers are no longer with the company.” Once again, a GM executive passed the buck to midlevel employees while taking little of the blame himself.

Another subcommittee member, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.)—a most penetrating questioner—asked Millikin whether GM would waive its (deceptively obtained) liability shield from lawsuits prior to its 2009 bankruptcy and taxpayer bailout, or whether it would make public documents related to the internal investigation of the defect. “We will not,” answered Millikin to both questions.

“Lawyers typically are supposed to be the corporate conscience,” Blumenthal says. “They’re supposed to be the ones that make sure that corporations comply with the law in spirit and letter. Here, the lawyers for GM actually enabled cover-up, concealment, deceit, and even fraud.”

Barra told the Senate committee that GM is taking steps to change the corporate culture that failed for 13 years to acknowledge the ignition switch defect. Barra spoke of firing 15 employees, “some for misconduct and incompetence, others because they didn’t take responsibility or act with a sense of urgency.” She talked of creating a Speak Up for Safety program meant “to encourage and recognize employees that bring potential safety issues forward quickly” as well as appointing a new global vice president of safety who would report to her. GM will also establish a fund to compensate people injured and the families of those killed because of the defective ignition switch.

The devil is in the details. GM’s lawyer, Ken Feinberg of Feinberg Rozen LLP, detailed the prerequisites for the compensation program, noting that there is “no aggregate cap on the amount of compensation GM will make available to eligible claimants.” The key word is eligible—it happens to exclude all of the millions of recalled GM cars with faulty ignition switches except for the original 2.5 million recalled Cobalts and Saturns.

“The fund failed to include other recalled vehicles and defects that resulted in deaths and injuries, and are barred by statutes of limitations or the GM bankruptcy,” Ditlow explains. “The least GM could do for taxpaying consumers who bailed them out is compensate them for their losses due to defects in GM vehicles. Even for ignition switch victims covered by the Fund, it will be difficult, if not impossible, for a consumer to prove that ignition switch failure caused a crash if all they have is their statement that the ignition switch cut off.”

History has shown that GM executives are willing to talk about safety only when they get caught misbehaving. After all, this is the company that in the past has dragged its feet on safety standards for years, such as with shoulder belts and airbags. Since GM sales are rising, concerns about losing customers seem to have gone away. That may help explain why the auto giant refuses to produce more information about its negligent practices, refuses to support proposed corrective legislation, and seems increasingly comfortable that any Justice Department criminal inquiry will not reach the upper echelons of GM management and will only result in a fine that GM can easily absorb.

What would it take to instill long-lasting change in a company that now has a storied history of selling unsafe automobiles?

One very simple solution would be for Barra to establish an independent ombudsman office. GM’s proposed global vice president of safety—another bureaucratic link in the hierarchical GM chain of command—does not inspire much public confidence that safety defects will receive the immediate action they require.

By contrast, an ombudsman would be authorized to receive, in complete confidence, the assertions of conscientious engineers and other internal whistleblowers and report them directly to GM’s CEO and president. This independent office could ensure that safety defects are taken seriously and that employees would be protected from retaliation or job loss.

It would then become the CEO’s direct responsibility to follow up on the ombudsman’s report and decide whether it warrants triggering federal regulation on reporting the discovery to the Department of Transportation.

GM could also introduce a monetary reward for safety reports by its engineers and other employees to the ombudsman that could help prevent death and injuries. There is a precedent for this: Many other companies here and abroad have long given assembly line workers rewards for proposing more efficient ways to manufacture products.

If there is any benefit to the current firestorm over GM, it’s been to bring attention to the urgent need for stronger auto safety authority and enforcement budgets for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration—something that’s been long opposed by auto industry powers and their congressional allies such as Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.). Now is an ideal time to strengthen NHTSA.

First and foremost, Congress must make it criminal for manufacturers and their officials to knowingly violate the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. Citizens must be given the right to sue NHTSA when it fails to enforce the Safety Act, and all industry meetings with NHTSA officials should have detailed minutes that are placed in a public docket within 48 hours. The agency’s pathetic vehicle safety budget, now at $134 million, must be tripled, starting with funding a research lab like those at other regulatory agencies such as the Federal Aviation Administration and Environmental Protection Agency. Today’s NHTSA rents lab space from Honda, a company that it regulates. The agency has no meaningful electronics and computer expertise, even though vehicles have become computers on wheels. NHTSA’s administrator admitted to Congress that the agency didn’t even know how the advanced airbags it mandated worked.

An added incentive to stop corporate cover-ups comes from Sens. Blumenthal, Bob Casey (D-Pa.), and Tom Harkin (D-Iowa), who have just introduced the Hide No Harm Act of 2014 (S.2615), which would make it a criminal act—with punishment of up to five years in prison—for a corporate executive to cover up a harmful or deadly safety issue. Such action is long overdue. Only by holding top corporate executives’ feet to the fire can we avoid these deadly mishaps in the future.