Economists everywhere may soon be thanking Seattle Mayor Ed Murray. Not because of his inspired policymaking, but because Murray seems ready to turn his city into a gigantic laboratory for one of the most ambitious, and quite possibly misbegotten, labor market experiments in recent memory.

Yesterday, Murray announced a plan that would gradually raise Seattle’s minimum wage to $15 an hour and tie it to inflation, which won approval from a large committee of business and labor leaders, as well as some city council members. Today, Washington state’s minimum is a comparatively piddly $9.32. The full council still has to consider Murray’s proposal, but should it pass, Seattle might not just have a far higher minimum wage than its surrounding suburbs, where businesses can easily move; it might well have the highest minimum wage in the world.

I generally support a higher pay floor. And I love a good experiment. But I can’t help but wonder if Seattle is poised to take a step too far.

The nationwide push for a $15 minimum wage that began with striking fast food employees has been a masterful public relations stroke. Its sheer audacity grabbed the media’s attention and has arguably reset the terms of the entire debate about worker pay. It has certainly made the proposal by congressional Democrats and President Obama for a $10.10 federal minimum look reasonable by comparison.

But while the fight for $15 has made for great politics—in Seattle, both mayoral candidates only adopted the idea last year after it was popularized by a socialist city council candidate, Kshama Sawant, who ultimately won her race—it’s built on dubious economics. The truth is, nobody has any idea what would happen if the minimum wage jumped that high. But there are good reasons to worry that results would be ugly.

The research literature on whether minimum wage increases kill jobs is decidedly mixed. Some economists have found that hikes lead to small job losses among teens and in industries like fast food. Others have found that losses are nonexistent, or at least negligible. In the end, I tend to argue that even if you assume reasonable job losses, middle-class and poor families come out ahead in the bargain. Though some workers end up unemployed, enough get raises to make the tradeoff worthwhile.

But that assumes we don’t lift the pay floor too high, too fast. Minimum wage studies have typically looked at small increases, somewhere around 50 cents or a dollar. Seattle’s proposal would be far larger. It would also have virtually no U.S. precedent. (Nearby neighbor SeaTac recently upped its own minimum to $15, but the city is little more than an airport and only 1,600 workers are affected.) Adjusted for inflation, the value of the U.S. minimum wage peaked at $10.66 in 1968, as shown in this American Enterprise Institute graph. That’s the ceiling on America’s historical experience.

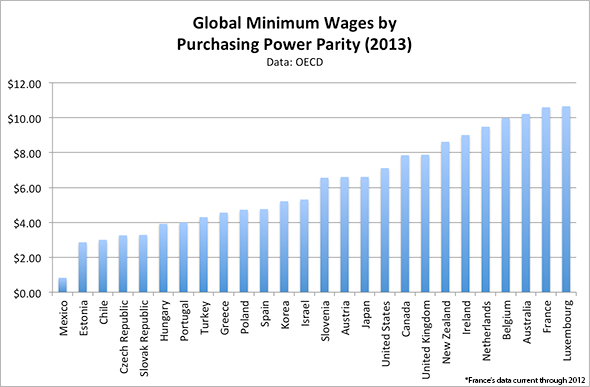

Seattle’s plan has little global precedent, either. As Tim Fernholz at Quartz notes, the city is essentially considering adopting the highest minimum wage on the globe. That may come as a surprise, if you’ve ever read about Australia’s roughly $15 minimum. But once you adjust for purchasing power, the wage floor down under, as well as in high-pay countries like Belgium and France, is closer to $10, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. If the Swiss vote to raise their minimum to $25, as they are considering, Bloomberg reports it would be worth just $14 on a purchasing power basis.

Slate

Any plan that makes hiring a worker more expensive than in France should be cause for concern. We know that businesses in high-wage countries are especially eager to replace workers with software. Fast-food restaurants in Europe, for instance, have been some of the earliest adopters of labor saving technologies like digital kiosks where customers can order. Those innovations are already beginning to make headway in the United States. But by passing a $15 minimum, Seattle would risk speeding the process up within its city limits.

Don’t take my word for it. Listen to Arindrajit Dube, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst economist who is perhaps the foremost advocate for the idea that minimum wage increases don’t kill jobs. “Would I be concerned about possible job losses if there were a $15 minimum wage in the restaurant industry, yes, I’d be concerned,” he told the New York Times in December. “There are concerns that it might lead to the substitution of automation for workers.”

The move is especially risky for a single city, where businesses can easily choose to open or relocate in the suburbs. That fear convinced Washington, D.C. to coordinate its own recent minimum wage increase with some of its surrounding counties. Seattle isn’t taking any such precaution. (Again, SeaTac is barely a city.)

To his credit, Murray is trying to implement the idea gradually. Under his proposal, businesses would have between three and seven years to phase in the new minimum, depending on their size and whether employees get health care coverage or tips. Through 2024, some businesses will also be able to count $3 worth of tips or benefits toward the $15 total. By introducing the change over time, the city will give businesses leeway to adjust, if they can.

If they can’t, however, the impact could be vast. Researchers at the University of Washington have estimated that 102,000 workers in Seattle make $15 or less, meaning they would be directly affected by the hike. Murray is running his experiment with a quarter of his city’s workforce.

And yet, for all the red flags, I’m oddly glad he’s giving it a try. If the plan passes, it will be fascinating, and instructive, to see how such a hike plays out in a major American city. If it succeeds, it could mean a profound shift in how we think about worker pay. If not, Seattle will have taken out the idea for a test drive. Better that one city’s job market crash than a whole country’s.