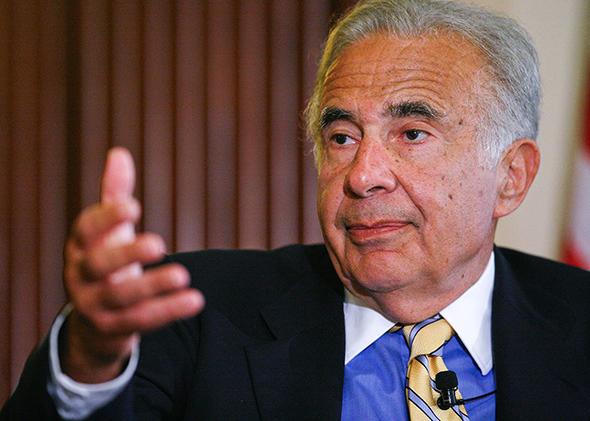

Carl Icahn, the 77-year-old billionaire investor, has an idea for Apple. It’s an idea he believes so strongly in that he’s bought 4.7 million shares in the company—a stake worth more than $2.5 billion. And he’s using every tool at his disposal to get Apple to use his idea, from social media to dinner dates to his latest move, a formal shareholder resolution. The only problem is the idea stinks.

If there’s one thing Icahn has proved over the course of his career it’s that he’s pretty good at getting rich. And his campaign for a massive share buyback will, if implemented, succeed in making him richer. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea for small-time Apple shareholders, for the millions of people who use the company’s products, or more importantly for the world at large. Quite the opposite. Icahn’s call for buybacks reflects a malignant streak running through American corporate culture, one that emphasizes financial engineering and trading over tangible investments.

The underlying issue is that Apple has money. Too much money. An unseemly amount of money. About $147 billion in cash and short-term investments.

To get a sense of how much that is, consider that there are exactly 31 publicly traded companies on the Financial Times Global 500 list whose total value exceeds $147 billion. Any other company, whether it’s Cisco or Intel or Amazon or McDonalds or Ford or what have you, is worth less in total than the amount sloshing around in Apple’s bank account. $147 billion is genuinely more money than any company has any reason to accumulate. And although it’s not sitting around in a desk drawer somewhere, it is held in low-yield short-term financial products that get very little return on investment in these days of low interest rates.

Willie Sutton said he robbed banks because that’s where the money was. These days, an awful lot of the money is in Apple’s cash accounts, so it’s become a natural target for corporate raiders: first David Einhorn and now Carl Icahn. Their ideas, while perfectly legal, really are the corporate equivalent of bank robbery. Icahn bought a bunch of Apple shares. Now, using his leverage as an Apple shareholder, he wants Apple to use its cash to buy a bunch of Apple shares. A huge buyback will, mechanically speaking, increase the price of Apple stock. That will let Icahn sell his shares at a profit and move on to the next thing.

But Apple as a firm won’t have gained anything in this process—it will simply have less money. The company, and all its shareholders who don’t cash out in the Icahn party, will just be worse off.

Apple CEO Tim Cook’s problem in resisting this campaign is that he lacks the conceptual tools to defy Icahn’s logic. Steve Jobs was flagrantly uninterested in the financial engineering aspects of business and simply socked cash away with no clear purpose in mind. Perhaps Apple’s near-death experience simply made him want to build up the biggest cash buffer imaginable so that the company could continue his pure vision even in hard times. When Cook took the helm, he decided it was time to start acting like a “normal” CEO and give back to the shareholder. He announced a share buyback and the beginning of a dividend program. But that only whetted Wall Street’s thirst for cash. This spring the dividend grew 15 percent and the pace of buybacks increased, but the company still has lots of cash, so it’s natural that Icahn and others want to get their hands on it. This is a road down which many American CEOs have been led, breaking the link between corporate profits and business investment.

The best way out of the bind is to get rid of the cash. How?

The options are almost too numerous to count. The fastest would be through acquisitions. This is the most fun option to think about as a bystander. Buy Tesla and revolutionize the auto industry. Buy Comcast or AT&T and revolutionize broadband distribution. But Apple’s never really been a mega-acquisition kind of company, and more prosaic options are out there. The company’s retail stores, for example, are extremely lucrative. In terms of sales per square foot, they’re not just No. 1—they double the sales of second-place finisher Tiffany’s. That’s a sign that Apple should be building more—and larger—stores, employing tens of thousands of extra people. This is how successful companies are supposed to behave, plowing profits into expansion to grow their own sales and expand the economy at the same time. Another obvious avenue for growth would be content, where Apple could join Netflix and Amazon in investing in original programming like Alpha House.

Last but not least, Apple could always cut prices for the sake of long-term growth. Apple’s marquee products—cutting-edge iPhones and iPads—seem to sell about as fast as they can make them. But Apple’s first-party cables are substantially more expensive than competing products, its accessories are expensive, and Mac computers continue to be a high-margin low-market-share product while the iPhone 5C isn’t the true low-cost smartphone the world’s been waiting for. Meanwhile, does a company that’s already this rich really need to be taking a 30 percent cut from app and music sales through its online stores? Every company is entitled to try to charge what it thinks it can get away with for its products and services. But executives should ask themselves to what end they’re soaking up this money.

Cook’s instinct—that just throwing it at Icahn doesn’t accomplish anything—is sound. But you can’t sock away endless billions and not expect people to come after it. You either need to invest the money in something real or stop soaking it up so quickly by cutting prices. Either option, or some combination of the two, would be better for Apple’s long-term future and better for the world economy.