“If you work for a living, you’re labor, too!” So read the text of a full-page newspaper advertisement sponsored by the American Federation of Labor in the spring of 1947. As the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act was wending its way through Congress, the AFL tried to convince the general public that it represented everyone, not just unionized workers.

This was a tough sell—and it still is. The chosen face of organized labor has long been the noble manufacturing worker, often one who produced machinery for American war efforts. This worker was white and male, he was his family’s sole breadwinner, and he probably wore overalls and muscles. Long after the AFL’s 1947 appeal, he remained the quintessential American laborer of the postwar period.

Courtesy of Reuther Library, Wayne State University.

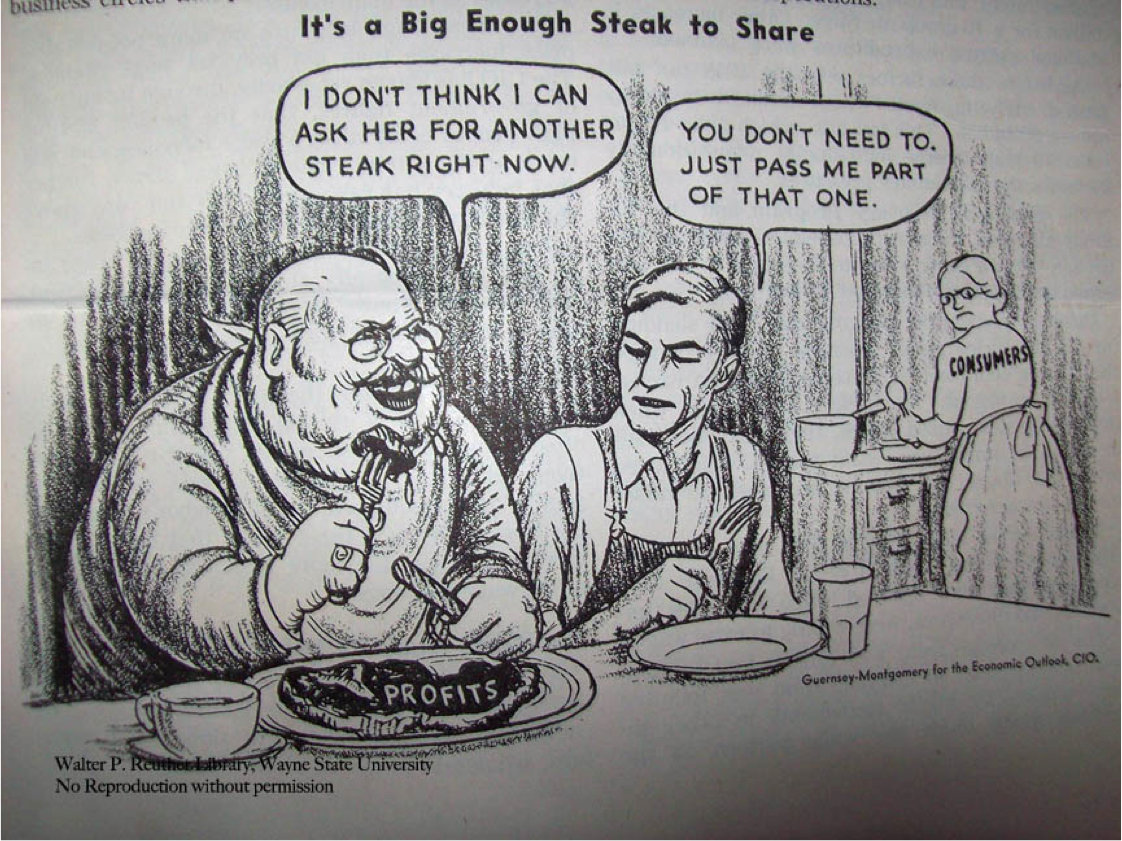

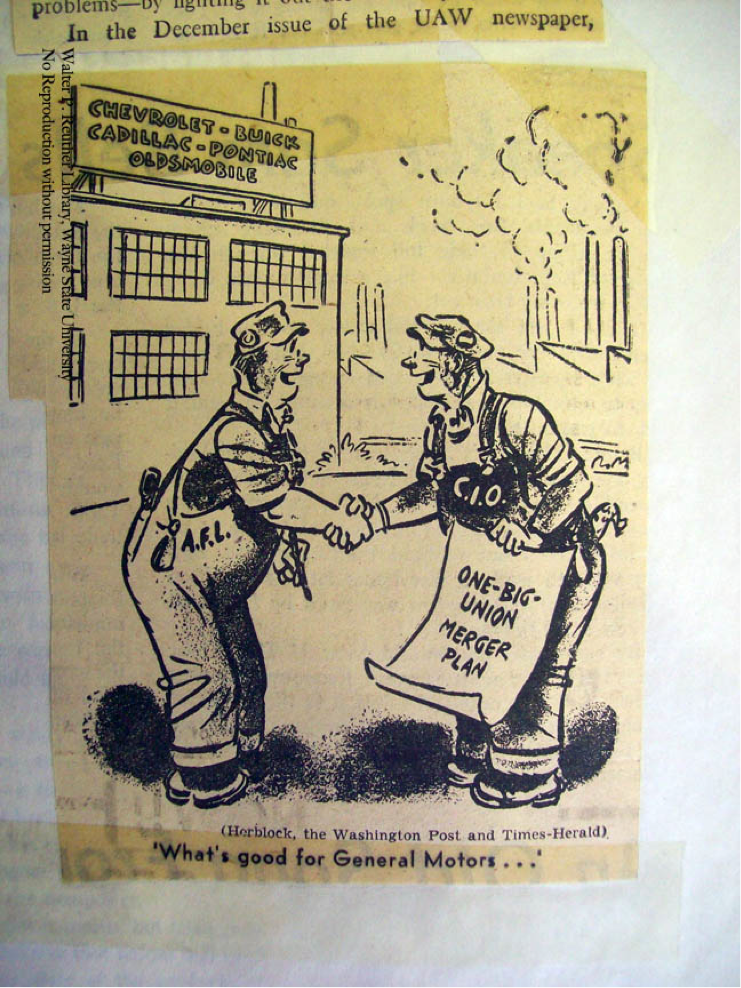

Successful branding efforts by the AFL and the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which joined forces in 1955, helped win both public support and more favorable contracts for their members. But the campaigns also carried hidden costs. The indelible image of the blue-collar working man now competes with the more diverse demographics of the actual American working class. That cognitive dissonance around what labor “should” look like is part of the challenge facing fast-food workers demonstrating for higher pay, better working conditions, and the right to unionize this Labor Day.

The demands of fast-food workers in some 60 cities across the country aren’t extreme or unusual. We might imagine a steelworker, autoworker, or miner making similar demands. But the burger flipper at McDonald’s or the cashier at Wendy’s doesn’t have a century-long heritage of imagery celebrating their contributions to the American economy. It’s harder to romanticize the work of service occupations, which employ nearly 18 percent of the American workforce, compared with about 9 percent in manufacturing jobs—a gap that will continue to widen as the service sector expands and manufacturing shrinks.

Yet food service workers are in far worse shape than those who work in manufacturing. The average hourly earnings of workers in nonsupervisory positions is just more than $11 an hour, with food-preparation and serving workers taking home less than $9 an hour, on average. (By contrast, steelworkers receive more than $24 an hour on average, and those in motor vehicle manufacturing are paid more than $27 an hour.) Fewer than 2.5 percent of food-service and accommodation workers are represented by a union, which would likely improve their wages: Unionized full-time food workers make $585 per week on average, compared to $424 for non-union workers.

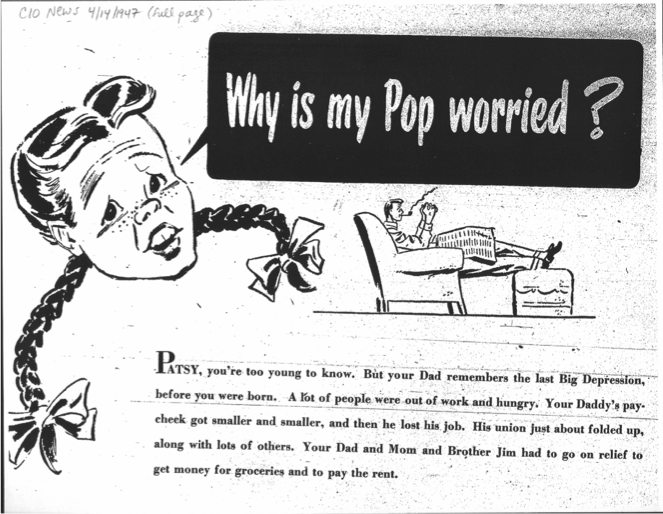

In the postwar period, union leaders would rally pubic support by stressing that the men of the labor movement had mouths to feed. In a 1947 newspaper advertisement against Taft-Hartley, the CIO featured a picture of a young girl asking, “Why is my Pop worried?” The answer: He might have to go on relief, just as he did during the bad old days of the Depression. “These three are all tied together—families, unions and the United States of America,” the ad argued.

Courtesy of Tamiment Library, New York University

Like “Pop,” the fast-food workers demonstrating across the country are often family breadwinners; 40 percent are 25 or older, and about 25 percent of them have children, according to the Center for Economic and Policy Research. But these breadwinner parents don’t look like Pop in many other respects. For one thing, 58 percent of food preparation workers are women. For another, among employed men, 22 percent of blacks and Latinos work in service jobs, compared with just 14 percent of whites. (Among employed women, 28 percent of blacks and fullly one-third of Latinas are in service, compared with 20 percent of white women.) And unlike Pop, they may not be big and brawny, even if the work they do is physically demanding.

Courtesy of Reuther Library, Wayne State University

The gap between our entrenched image of the working class and its demographic reality creates a paradox. On the one hand, it’s clear that unionizing would make the lives of millions of service-industry workers better. On the other, if unions were built to protect the industrial worker in overalls, it’s easy to see why the public might think that as those workers become fewer and farther between, then union power should shrink accordingly.

That perception needs to be shattered for fast food workers to win higher pay, better working conditions, and the right to unionize. As we celebrate Labor Day this year, we should rethink our concept of labor—and of who really does the laboring.