In the days before the housing crash and the financial crisis, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—two private companies existing under government “sponsorship”—played a key role in the country’s housing finance system. By buying up mortgages from banks nationwide and then repackaging them as mortgage-backed securities, they allowed lenders to make more loans. These government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs, also shaped the nature of the national mortgage market, ensuring the existence of the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage that’s standard in the United States but rare elsewhere. In the meantime the companies made lots of money for shareholders. The implicit federal seal of approval gave them access to low-cost debt, which made it easier to make money by buying up home loans. That meant hefty salaries for executives and nice returns for shareholders. A good time was had by all, until the mortgage market came crashing down in 2008 and Fannie and Freddie found themselves in need of more than $100 billion in bailout money.

This textbook example of privatized profits and socialized losses has outraged normal people from the moment it was announced. But the Fannie/Freddie bailout was handled differently from the bailouts of major banks: Fannie and Freddie are now owned by the United States government. As the housing market has turned around, they’re once again earning profits—profits that are paid to the Treasury as dividends. Big dividends. So far the Treasury has gotten more than $146 billion from the GSEs; later this year the total amount of dividends paid will exceed the $187.5 billion they’ve gotten from the government. The investment, in other words, is actually looking pretty smart over and above the economic benefits of keeping the mortgage market going.

The only problem is that this gusher of federal revenue is actually an economic disaster.

In normal times, government coffers filled with dividends would be good because they could be put to some use. The government could spend that money on building Hyperloops or repairing schools or vaccinating children. Alternatively, the government could do the exact same things it was doing before, but reduce taxes and put more money in working peoples’ hands. But that would require a functioning political system. Today’s gridlocked Congress isn’t doing anything with the money.

Still, under ordinary circumstances the reduced government borrowing that results from a dividend windfall could be useful. A smaller deficit often allows the Federal Reserve to run lower interest rates without sparking inflation. That makes it easier for people to buy houses or for firms to invest in new production. Today, though, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation is running at its second-lowest level on record, even though short-term interest rates have been at zero for years now.

So the Treasury is earning tons of Fannie/Freddie money. But the profits aren’t letting us spend more, they aren’t letting us tax less, and they aren’t freeing up private investment capital either. They’re doing nothing. It’s as if the money were sitting around as cash in a storage locker somewhere.

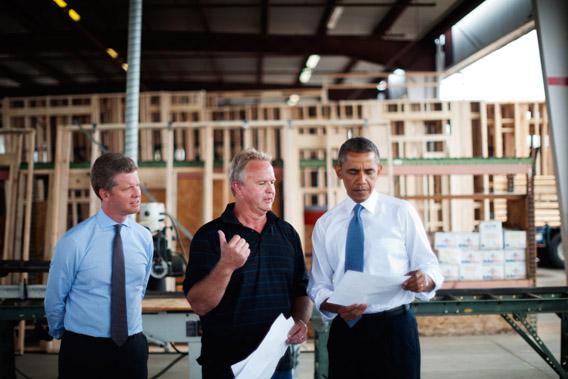

What’s more, the money is very likely to keep piling up for quite some time. Essentially everyone in Congress agrees that the current situation, in which Fannie and Freddie are government-owned and dominate the mortgage market, should end as soon as possible. But they disagree about what, specifically, should happen next. Back on Aug. 6, the White House tried to put housing finance reform on the agenda with a speech endorsing legislation by Sens. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., and Mark Warner, D-Va., that largely tries to restore the pre-crisis status quo while drastically reducing the odds that the federal government will have to step in with bailout money in the future. But in the House of Representatives, Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling, R-Texas, steered a much more radical bill through committee that would eliminate Fannie and Freddie and replace them with nothing at all, leaving the mortgage market without the government backing it’s enjoyed since the Great Depression.

This is a fundamental clash of visions that’s hard to compromise away. What’s more, even though everyone says they want to end government ownership of the GSEs, there’s no particular deadline for getting it done. That means the issue is likely to stay on the back burner than get resolved.

Under the circumstances, it’s worth wondering if there isn’t something more economically constructive we can do with Fannie and Freddie while waiting for Congress to figure out the long-term picture.

Rather than paying dividends to the Treasury, the GSEs should pay dividends to the American people—writing checks to you and me. That way, conservatives can stop grousing that the reverse bailout is an Obama plot to make the deficit look small. More importantly, the profits can recirculate through the economy rather than sitting inert in the vault. People with more cash in their pockets will buy more goods and services. Firms facing increased demand will boost production and hiring. The increased tax revenue and decreased social service payments associated with a greater level of economic activity will partially offset the lost money to the Treasury.

As long as we’re stuck with the government owning two big companies nobody thinks it should own, we might as well let John and Joan Q. Public in on a little fun.