Last Friday, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos sold a bunch of Amazon stock. On Monday afternoon, we learned why. Bezos is buying the Washington Post for $250 million. The news—combined with the sale of the Boston Globe over the weekend for $70 million to the quantitative trading pioneer John Henry—has prompted a fair amount of gnashing of teeth and rending of garments over the much higher prices fetched recently by Tumblr and Instagram, and of the possible trampling of American democracy by egomaniacal newspaper-buying billionaires. While it’s of course possible that Bezos will ruin the Post or turn it into some kind of adjunct to Amazon’s lobbying efforts, we should more likely see this as a positive development.

The most journalistically successful American newspapers have almost always been family affairs, conducted in part out of non-pecuniary motives. Conversely, the sky-high valuations given to social networking startups reflect the belief that the industry has a high degree of potential for monopolization and network effects. For years, everyone has bought Microsoft Office not just because it’s good software but because everyone else uses Office and it’s important to be compatible. That’s a great kind of business to be in if you’re an investor, but the news-reading public should be thrilled that nobody thinks the media is that prone to monopolization.

It’s also important to be clear on what Bezos did and didn’t buy. In particular, he did not buy the Washington Post Co. The Post Co. is named after the Washington Post, but its biggest source of revenue is the Kaplan family of education services companies and its main drivers of profit are a number of local broadcast television stations and Cable One, the nation’s 10th largest cable TV provider. The Post Co.—which is going to have to be renamed—also owns Slate, Foreign Policy, and The Root, none of which are being sold. Overall it’s a very diverse company, with interests ranging from hospices to the manufacture of industrial equipment. The biggest drag on its financial results was the Post newspaper, which is saddled with legacy costs and an ongoing contract dispute with the Newspaper Guild. The paper may well have a bright future as a business, but the road from here to there is unclear.

What’s more, if that future involves anything other than steady shrinkage, it’s a road that will entail substantial outlays in the form of transitional operating losses and new investments. The Post Co. has enough operating surplus from its other business units to do that, but Chairman and CEO Donald Graham would have to justify any such investments to shareholders. Why cover the Post’s losses rather than pay more dividends? In the context of a publicly traded company, the decades-long ties between the Graham family and the newspaper could have even become a hindrance. Any Graham vision of revival would sit under a cloud of suspicion that he was actually bleeding shareholders for the sake of family sentiment.

Bezos, meanwhile, is a famously patient CEO of Amazon, putting growth and an excellent customer experience first and trusting profits to follow. As sole owner of the Post, he’ll be able to follow his vision for good or for ill. He’ll be able to manage it with an eye toward his larger business interests, but without needing to explain himself to Amazon shareholders.

It would be silly to say that the rise of public ownership is the main cause of financial worries at American newspapers. But it’s hard to escape the conclusion that, from a journalistic viewpoint, the most influential work in newspapering has come from outlets associated with strong family ownership. The Sulzbergers in New York, the Chandlers in Los Angeles, the McCormicks in Chicago, the Bancrofts at the Wall Street Journal, and the Grahams in Washington: All of these owners wanted to make profits, but they owned newspapers specifically because they wanted to own newspapers and had journalistic vision. Even Rupert Murdoch fits the bill. And this kind of vision is important even from a financial point of view. Just as people don’t want transactions with their doctor to resemble transactions with a used-car salesman, there’s an appeal to getting your news from someone who believes in news.

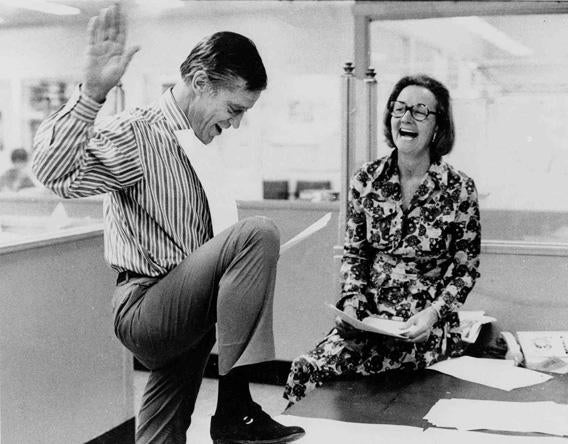

Katharine Graham, then publisher of the Washington Post, and Executive Editor Benjamin C. Bradlee look over reports of the 6 to 3 Supreme Court decision which permitted the paper to publish stories based on the secret Pentagon study of the Vietnam War, in this June 30, 1971 file photo.

Photo by Charles Del Vecchio/The Washington Post/Getty Images

But no family company can last forever. It’s natural that as time passes and the number of descendants grow, pressure mounts to let ancillary family members cash out by taking the company public. This worked fine in the era of fat newspaper profits, but public ownership and a challenging period of technological transition are a bad match. Cross-industry surveys show that publicly owned firms underinvest compared with privately held ones, largely because decisions need to be made with an eye toward the next quarterly earnings report. But whatever steps an old brand like the Post needs to take to succeed in the long term, they have nothing to do with the steps that will produce the best-looking financial statement three months from now. That means private ownership, most likely by idiosyncratic individuals willing to take risks on ideas that might fail.

Henry’s purchase of the Globe fits this model best, as he has deep roots in the Boston area (for example, he owns the Boston Red Sox). But Bezos’ move—and even the potential purchase of Tribune newspapers by the Koch brothers—is close enough for a 21st-century media landscape. These transactions should be seen not so much as the end of an era, but as a necessary recycling of control. A business that’s always somewhat depended on bigwigs more interested in challenge and prestige than pure profit maximization is naturally going to need some new bigwigs once in a while. It’s the circle of life.