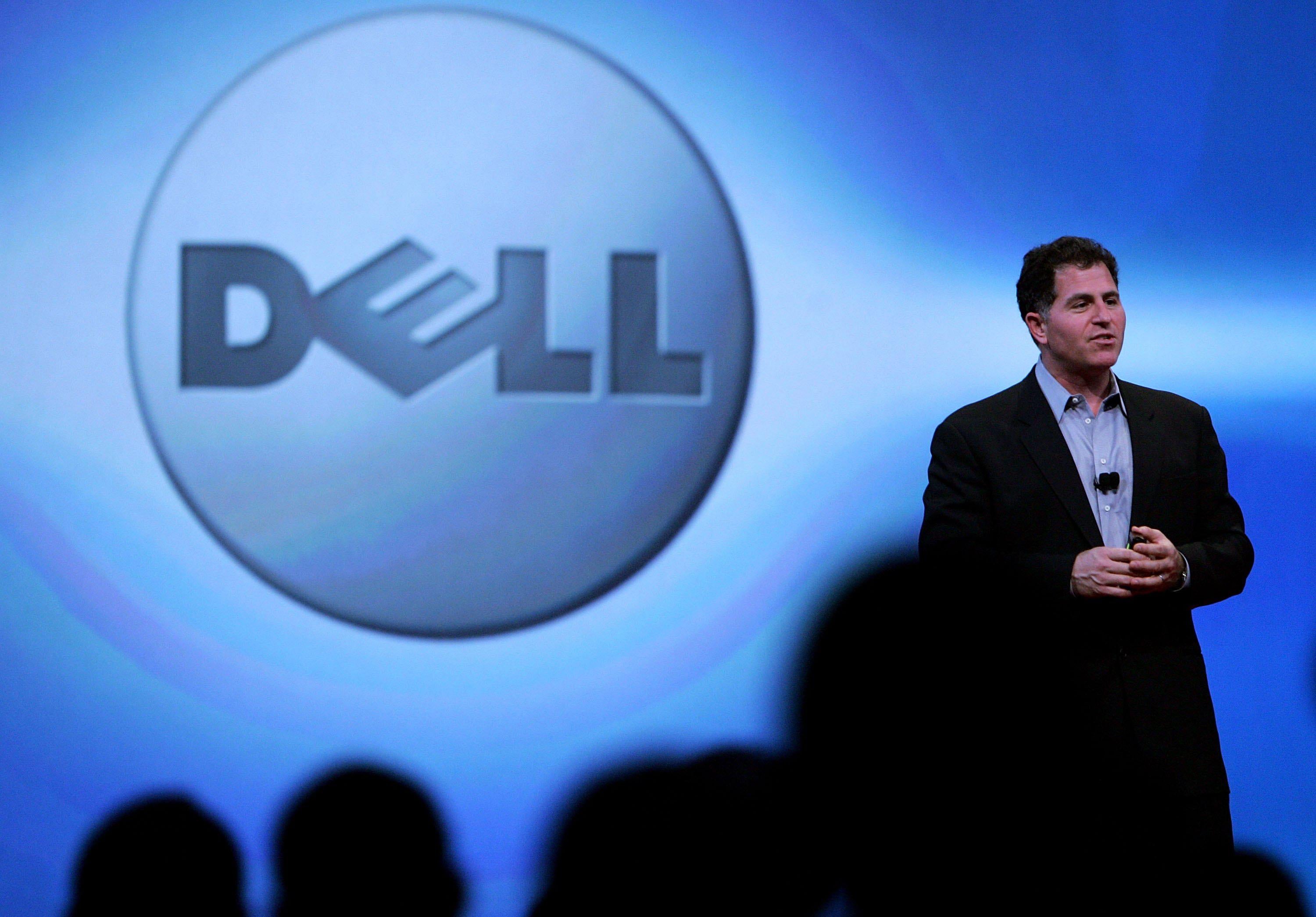

The proposed leveraged buyout of Dell by its own founder and CEO is making headlines largely for its sheer size. Michael Dell, in partnership with private equity fund Silver Lake Partners and with financing from Microsoft and four banks, is proposing a $23 billion buyout of the computer company. One of the largest buyouts on record and by far the largest since the financial crisis, the Dell deal would be the clearest sign yet that the financial system is back. But more interesting than the financing is the reason for the deal: It is essentially a large-scale tax-avoidance scheme.

Leveraged buyouts have long been a controversial topic, and Mitt Romney’s presidential bid put them in the partisan spotlight. But these deals vary widely according to circumstance. Where some see “vulture capitalists” destroying firms and lives, others see a much-needed mechanism to bring greater efficiency and new management to troubled enterprises.

The Dell deal is striking in this regard because the key mover is already the CEO, founder, and largest shareholder in the firm. In other words, while Michael Dell may have some new ideas about how the company should be managed, the deal is clearly not about wresting control of the brand from mismanaging incumbents. The idea is to keep the same leadership team in place, and rejigger the company’s financial structure rather than its way of doing business.

The main function of taking a company public is to give early investors and employees a way to turn their shares into money. Subsequent trading lets secondary investors—and executives with stock options—get paid as well. As long as a company is growing rapidly and its share price keeps rising, the stock market keeps performing this function admirably. People who are paid partially in shares (or who have shares from previous payments) can cash out into a rising market. The problem arises when, as with Dell, your firm enters a period of market stagnation.

Dell’s basic business problem is obvious. The PC market is shrinking in the face of the rising popularity of tablets and smartphones, and incumbent PC makers are seeing their profit margins challenged by new entrants such as Asus and Lenovo. Dell’s hope is to imitate IBM’s successful transformation into a software and services company. But IBM’s turnaround is such a famous business story precisely because it’s rare and difficult, and not something that Dell can obviously repeat. Meanwhile, Dell, as it currently exists, continues to be a profitable company, and thanks to past profits, it also has a lot of cash on its books—much of it squirreled away offshore to avoid taxes.

And here’s the rub. Dell’s cash stockpile and current profits ought to make it a valuable company despite its poor growth outlook. But before those profits or cash holdings can be paid out to shareholders as dividends, they would have to be “repatriated” to the United States. Then a 35 percent corporate income tax would be levied, and only then would shareholders get their money.

A leverage buyout offers a workaround to avoid many of these taxes. Shareholders make money directly as their shares are bought back at a premium. Much of the money that would go to buy the shares would be borrowed from banks, who’ll earn a profit of interest payments. Those interest payments can be made, in part, with the repatriated cash. Except this time the cash would not be taxed, since interest payments on corporate debt are a tax-deductible expense. Like magic, Dell’s shareholders would be extracting money from the firm without giving Uncle Sam nearly as big a cut.

To say that’s all there is to the deal would be an exaggeration. Obviously Michael Dell sincerely hopes that freeing himself from the distractions of monitoring day-to-day stock fluctuations will better help him execute his pivot, but tax arbitrage is a huge part of the story. This important aspect of private equity’s role in American finance is somewhere between the heroic job creator image and the life-destroying vulture capitalist one. Huge sums of money are involved and structuring the deals is complicated work, but it’s essentially the banal work of accounting helping a company maximize its tax deductions. Reforming the corporate income-tax code to feature lower rates and fewer loopholes so that less time and energy are wasted on this kind of thing is something everyone in Washington says they want to do but somehow never seem to get done. Until they do, expect to see more eye-popping deals that are basically about financial engineering rather than business strategy.