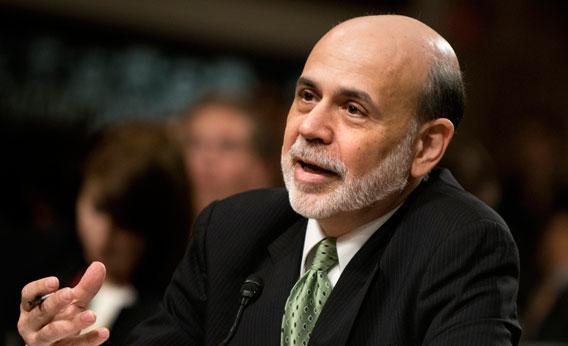

The upcoming Federal Reserve meeting on June 19-20 will be one of the most important events of the entire year. Faced with an economic outlook that’s clearly weaker than it was six months ago, the central bank ought to undertake a more stimulative course of action. And yet, there’s little indication that the Fed’s governors are considering any such thing. Even more remarkably, there’s almost no pressure coming from inside the political system for the federal government’s main macroeconomic stabilization agency to stabilize the economy. Instead, when Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke went to the Hill last week, he was hectored by conservative members calling for tighter money, while Democrats did nothing to call for the sort of pro-growth policies that represent their best hope for November.

The left ought to be lobbying Bernanke for a looser money supply and more quantitative easing. Instead, the only criticism from the left that Bernanke took on the Hill was over the relatively unimportant subject of JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon’s role on the New York Federal Reserve Bank’s board of directors.

It’s just not Democrats on the Hill who are ignoring the truly critical matter of Fed policies. As the annual Netroots Nation conference this weekend in Providence, R.I., attendees were all-too-aware that the weak economy is the biggest short-term threat to their larger political project. At the same time, they remained woefully uninterested in the subject of monetary policy, the main tool the government can use to boost the labor market. Instead, the economic policy discussion among progressives remains fixated on the politically impossible and substantively inadequate concept of fiscal stimulus. A Saturday-morning high-profile economic policy roundtable featuring Paul Krugman, AFL-CIO chairman Richard Trumka, and progressive think tankers Heather McGhee and Erica Payne drove this blind-spot home. The Federal Reserve was discussed only glancingly, and even that segment myopically focused on Dimon’s New York Federal Reserve role.

In translating their ideas to the activist audience at Netroots, Krugman and others tend to skip over the fact that monetary stimulus from the Fed is pretty clearly necessary. Just ask yourself what the world would look like if some optimal fiscal policy were enacted and growth accelerated to the point at which we were adding 300,000-400,000 jobs a month instead of 100,000-200,000 jobs.

Well, millions of new workers would start burning gasoline and commuting to their new jobs. Millions of Americans would start moving out of their mom’s basement or their sister’s spare room to rent their own place. They’ll be running their own heaters and air conditioners. They might eat out a bit more often, and cook a bit less rice and beans and a bit more meat.

Those are all good things—but would mean higher prices.

There’s plenty of slack and idle resources in the economy, but we don’t have vast tankers of unemployed gasoline and the supply of rental housing is pretty low. In my opinion, a temporary price surge would be a small cost for a return to full employment. Or to put it another way, keeping the country on track for a years-long spell of mass unemployment is a shockingly stupid and immoral way to ensure cheap gasoline and affordable bacon.

A century ago populist leaders like William Jennings Bryan denounced the hard-money advocates of the era as wanting to “crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” But modern-day populists are largely out to lunch, downplaying the importance of monetary policy in economic health. Krugman, normally the least polite man in punditry, confessed to going soft on Bernanke because he knows him personally from the Princeton economics department. Payne briefly raised my hopes by reading aloud the phone number of the Federal Reserve’s public affairs department in Washington, urging the audience to call in. What she wanted people to complain about, however, wasn’t mass unemployment: It was the fact that Dimon is on the New York Fed board.

The problematic structure of the Federal Reserve, whereby banks are regulated by an institution whose leaders are selected, in part, by banks, is a real issue. That said, the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill already improved matters. There are more reforms that could be done, but hectoring Dimon into resigning would barely even change anything. He’d merely be replaced by another banker, and the larger dynamic in which the CEOs of enormous multinational banking conglomerates have privileged access to regulators and policymakers would stay in place.

On monetary policy, by contrast, the difference between the Fed’s current posture and a change of course would be dramatic. Bernanke assured members of Congress that he stands at the ready to bolster the American economy if shocks from Europe or elsewhere slow us down. What the country needs, however, is to speed up, no matter what happens in Europe. A clear statement that the Federal Reserve thinks higher prices for rental housing and primary commodities would be a small price to pay for an end to mass unemployment is a necessary condition for avoiding years of sluggish growth. But the central bank is extremely unlikely to change direction when nobody’s pushing them to. Getting monetary policy right lacks the interest group appeal of the American Jobs Act, the poetic grandeur of a massive public works program, or the basic emotional appeal of complaining about out-of-control bankers. There’s nothing wrong with talking about any of those things, but none of them change the fact that rapid recovery is all-but-impossible without cooperation from the central bank.

For conservatives, who on some level can’t be too disappointed with a weak economy that “proves” Obama to be a bad president, this indifference to monetary policy is understandable. But liberal inattention to monetary policy is baffling. If liberals can’t get monetary policy right, they can’t fix the economy and if they can’t fix the economy, the rest of their agenda will go down with it.