The death on Friday of Adam Yauch, best known as the Beastie Boys’ MCA, surely sent many of us back to old albums we may not have heard for a while. And anyone who threw on Paul’s Boutique, the Boys’ best album, was surely struck by the sense that they don’t make records like that anymore. That’s not just because tastes and styles have changed. The entire album is based on lavish sampling of other recordings. “Shake Your Rump,” which leads Slate’s #MCATracks playlist, features samples of 14 songs by 12 separate artists. In all, the album is thought to have as many as 300 total samples. The sampling gave Paul’s Boutique a sound that remains almost as distinctive today as it was when it was released in 1989.

Perhaps the main reason—and certainly the saddest reason—that it still sounds distinctive is that a rapidly shifting legal and economic landscape made it essentially impossible to repeat.

In the late 1980s, sampling occupied a legal gray area. The principle of “fair use” of material clearly (and fortunately) allows for the quoting of copyrighted text. Music samplers argue that the same right to quote belongs to them. In the case of text, the permissibility of quoting goes essentially unquestioned. If book reviewers needed the author’s permission to quote a work under review, meaningful criticism would be impossible. The back-and-forth, you-said-I-said dialogue of the blogosphere would be against the law. Historians wouldn’t be able to quote historical newspaper accounts of the events they’re describing. Where exactly the line is between quoting someone’s writing and straight-up copying it is often unclear, but the need to preserve a healthy space for quotation is uncontroversial.

Hip-hop sampling began as a live technique, with DJs working turntables at parties and clubs. Whether it was strictly legal or not, nobody was going to try to sue anyone about it. As the genre’s popularity grew, people naturally started recording performances and releasing them as albums. Early sampling tended to come fast and furious. In the ’80s, short clips of existing recordings were the order of the day, often—as in the case of the Beastie Boys—lots of them, layered and shuffled in a clearly creative way. As hip-hop pushed further into the mainstream, however, the stakes got bigger and so did the samples.

1990 saw the release of both M.C. Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This” and Vanilla Ice’s “Ice, Ice, Baby.” Not only did both songs sample, they each relied heavily on one particular sample—the baselines from Rick James’ “Superfreak” and Queen and David Bowie’s “Under Pressure”—for their main hook. Both hits resulted in legal controversy. Ultimately Hammer settled out of court with James, giving him co-composer credit and a share of royalties, and Bowie and Queen received songwriting credits for “Ice, Ice, Baby.” In 1991 came the case of Grand Upright Music v. Warner Bros. Records in which Biz Markie and Warner were enjoined against further distribution of his album I Need a Haircut on the grounds that “Alone Again” contained an unauthorized sample of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “Alone Again (Naturally).”

In the specific cases of “U Can’t Touch This” and “Ice, Ice, Baby,” paying off the original artists seems like a fair outcome. But the systematic consequences of these three precedents ensured that the methods of Paul’s Boutique would vanish from mainstream music.

After the legal turmoil, record companies didn’t want to expose themselves to copyright risk. Sampling was fine, but it would have to proceed on the basis retroactively agreed to by Hammer and Ice. Some form of explicit licensing arrangement would need to be worked out in advance with the rights holder of any recognizable sample. For songs in the specific mold of “U Can’t Touch This”—rapping over a lengthy excerpt of a well-known tune—this model works perfectly well and gave the world hits like Puff Daddy’s “I’ll Be Missing You” (borrowing from the Police’s “Every Breath You Take”) and “Come With Me” (borrowing from Led Zeppelin’s “Kashmir”). But it’s neither logistically nor financially feasible to contact hundreds of separate artists to win permissions for a complicated, sample-based album. And record labels don’t want to take the risk of exposing themselves to hundreds of potential lawsuits.

The art of heavy sampling survives, but only on in the margins. Under the stage name Girl Talk, Gregg Michael Gillis has released a number of popular and well-regarded pure mashup albums. But he does it with a specialty record label, Illegal Art, dedicated to keeping the genre alive. And the albums are available for download on a “pay what you want” basis, with the exception of his latest, which is free.

Even as hip-hop is more mainstream than ever, one of the key musical innovations has been pushed to the margins. That should serve as a reminder that the battles over intellectual property don’t merely pit the economic interests of creators against would-be freeloading consumers. The existing stock of recorded music is, potentially, a powerful tool in the hands of musicians looking to create new works. But it’s been largely cut off from them—for no good reason. Congress could enact a mandatory licensing scheme in which you pay a modest fixed fee to sample an existing recording for commercial purposes. Or it could create a legislative safe harbor, stipulating that samples under some set length automatically qualify as a fair use. But it won’t, because in the music and movie industries, the only kind of copyright laws Congress is willing to pass are ones that give more power to copyright holders, not less.

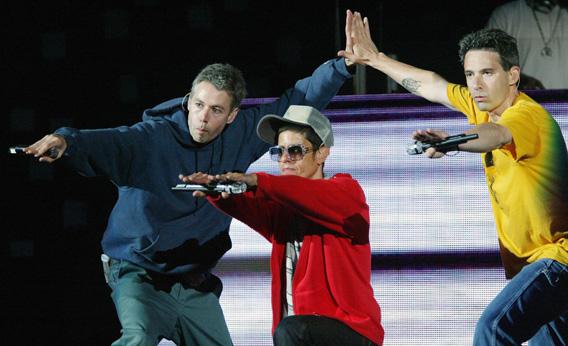

Correction, May 7, 2012: Because of a photo-provider error, the image accompanying this article originally misspelled Adam Horovitz’s last name.