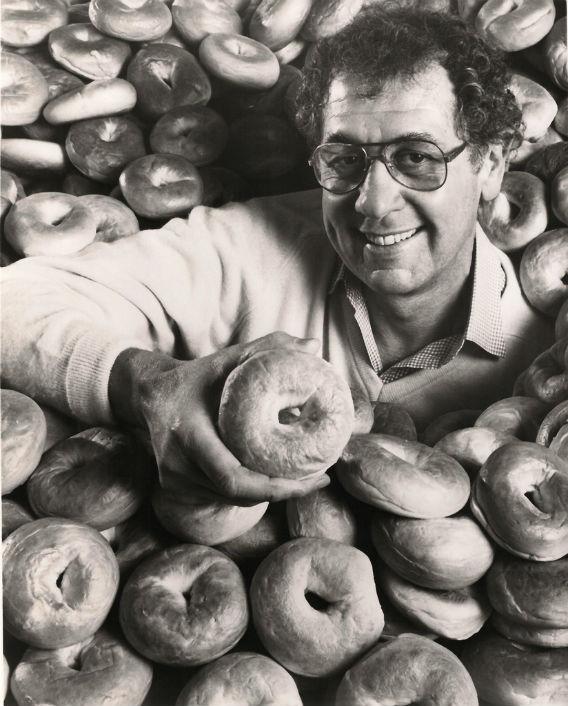

Innovation is often thought of as coming with better products. But sometimes the most successful innovations involve coming up with inferior products, but making them cheaper and more convenient. So it was with the late Murray Lender, former CEO of Lender’s Bagels, who passed away last week at the age of 81.

After a long and successful life, it was fitting that Lender died in March—National Frozen Foods Month. (Frozen Foods Month appears to be an imperialistic outgrowth of Ronald Reagan’s 1984 proclamation declaring March 6 National Frozen Food Day, undertaken at the behest of the National Frozen Food Association, now the National Frozen & Refrigerated Food Association, then chaired by none other than Lender himself.)

The family business was started by Lender’s father Harry in New Haven, Conn., in 1929. Initially, it was a conventional wholesale bagel bakery, catering to the New Haven Jewish community and gaining some popularity among non-Jewish locals as well. But the Lenders had a basic problem of production timing. Demand for bagels would surge on weekend mornings and plummet during the rest of the week. Unevenly timed demand is the bane of the food service industry. In order to produce enough product to meet demand at peak hours you need a very large space and lots of labor, most of which goes idle for huge swathes of the week. This entails an inefficient level of overhead and makes it difficult to retain employees, since people don’t like working irregular hours.

“All hell broke loose from Saturday morning until Sunday morning,” Murray explained to Maria Balinska, author of The Bagel: The Surprising History of a Modest Bread. “We would bake constantly—anywhere from 3,000 to 6,000 dozen because that’s when everyone ate bagels.”

Who exactly came up with the idea of freezing the bagels is a matter of some dispute, but it’s generally agreed that it was in 1954 that Harry had a portion of the garage converted into a storage freezer. Now the baking work could be smoothed out over the course of the week, with the previously hectic Saturday-night shift transformed into a leisurely matter of laying some bagels out for defrosting. The family attempted to keep the frozen nature of the bagels a secret, and even succeeded for about two years, until an accidental delivery of frozen bagels exposed them.

Balinska says the relatively small size of the New Haven Jewish community may have helped the Lenders because “in a smaller township, ethnic communities intermingled more” giving them an early edge in marketing bagels to non-Jews. More likely it helped bail them out when the frozen nature of the product was unearthed. In a richer bagel economy with many wholesalers selling to many retailers, each of whom vigorously competed for business, any fall-off in quality might have been ruthlessly punished by the market. But the Lenders appear to have had New Haven bagel eaters as a largely captive market. In the hands of uncreative people, that would be a recipe for laziness and mediocrity. But the Lenders, with their workflow-smoothing use of the freezer, proved to be innovators in the field of mediocrity.

Once they succeeded in persuading bakeries to keep accepting and reselling their product, it became clear that in the right context a wholesaler able to provide frozen bagels on demand could have a leg up. The Concord Resort in the Borscht Belt was interested in the possibility of maintaining a steady stock of bagels at a remove from New York City and became the first clients specifically looking for frozen bagels. Murray was the one who struck the deal, and later the one who came up with the idea of slicing the bagels before freezing them, since defrosted bagels tended to develop a hard-to-cut moist exterior.

But the main way Lender’s changed the world was by arriving on the supermarket shelf. Frozen, the bagel became an exploratory food. Fresh-baked products can only be sold in places where you know for sure that demand is high—otherwise they go stale. Baked goods thus tend to be conservative and intensely regional. The freezer changes all that. A frozen product can venture out into uncertain waters and survive as a niche product even if volume isn’t enormous. When my New York family went on vacation in Maine, Lender’s Bagels were there waiting for us at the IGA. Once the bagel went out into the world in frozen form, new customers discovered the product and the bagel became a nationally available foodstuff. New customers for frozen bagels created new demand for fresh ones, and now bagels are widely available all across America—albeit in severely bowdlerized form, much too big and lacking the textural contrast produced by poaching the dough before baking

The fundamental story of Lender’s Frozen Bagels is that the winning product isn’t always the best one. Like Ikea for furniture, H&M for clothing, or the Olive Garden for Italian food, Lender’s innovated by finding a way to compromise on quality and reap huge gains in other spheres. To an extent, it’s thankless work. Nobody wants to stand up and proudly proclaim, “I changed the world with my inferior products.” But often this is how the world changes. And if you look at the health care and higher education corners of the American economy where spiraling costs are bankrupting the middle class, you see sectors that are largely untouched by this kind of low-end innovation. The world could probably use a few more Murray Lenders.