The politics of corporate income tax reform are excruciatingly difficult, but the basic policy is easy. Taxes should be broad-based and the rates should be relatively low. The reality is the opposite: Loopholes and deductions proliferate, meaning rates need to be high in order to raise meaningful revenue. The problem here is that the higher the headline rate the greater the benefit of the loopholes and deductions, so firms expend even more time and effort on gaming the tax code rather than running a business. That’s how the United States manages to levy one of the highest corporate income tax rates in the world while raising very little revenue.

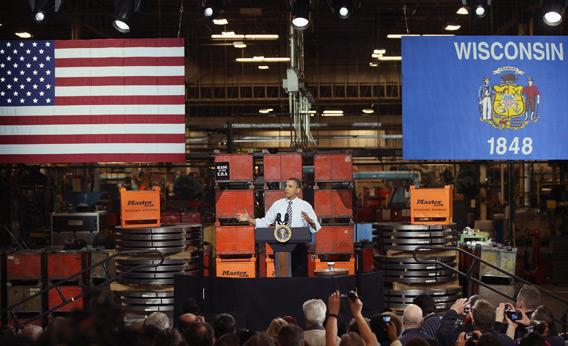

Under the circumstances, the main principles of the Obama administration’s proposed reforms to business taxation are just right. Obama would, by closing specified loopholes, cut the headline rate from 35 percent to 28 percent while slightly increasing the overall quantity of revenue raised.

The fly in the ointment is that he also wants to create a new loophole that would, in the words of the Treasury Department’s official briefing on the plan, “effectively cut the top corporate tax rate on manufacturing income to 25 percent.”

This puts some meat on the rhetorical bones of the most recent State of the Union address’s manufacturing fetish, but it doesn’t make much economic sense. The North American Industrial Classification Scheme divides the economy into just 20 broad sectors, of which one is manufacturing. Manufacturing is, indeed, a beautiful, unique snowflake with some attributes not widely shared by other sectors. But Educational Services, Transportion and Warehousing, and Utilities are all, in their ways, special too. The question is whether manufacturing is special in a way that justifies special subsidies. The two main reasons for subsidizing manufacturing, according to both the Treasury outline and a recent Brookings Institution paper, are that manufacturing pays premium wages to low-skilled workers and that manufacturing disproportionally contributes to private sector R&D spending.

Arguments typically establish those facts, then move on to describing the desirability of R&D and high wages. This skips a step. If it’s true that manufacturing is disproportionately involved in R&D, then that’s an argument that manufacturing firms would benefit disproportionately from R&D subsidies—not that manufacturing subsidies are a smart way to promote R&D. After all, even if on average manufacturers are investing more in research, some will be doing more than average and some will be doing less than average. Why should all firms get the same subsidy regardless of what they actually do, based simply on their NAICS code?

The wage issue is even clearer. The great thing about manufacturing, from a worker’s eye view, is relatively high pay. From a firm’s eye view, this is precisely the problem. The existence of a manufacturing wage premium does a great deal to explain why American companies have tried so hard to shift production overseas or to automate it here at home. Taxing the service and agricultural sectors in order to subsidize manufacturing is one way of slowing the erosion of manufacturing jobs. But this forces waitresses and cashiers to subsidize factory workers. If we want to transfer resources to less-skilled workers, we should tax wealthy people (including wealthy people who work for manufacturing companies) and subsidize the wages of all low-income people with a more generous Earned Income Tax Credit.

If the United States were a pre-industrial economy, manufacturing subsidies would make sense. Consider a country like India or China with a vast population of poor farmers. In an established agricultural society, the marginal agricultural laborer is normally working on a very small or simply undesirable patch of land. If you shift a worker out of farming and into factory work, not only do his wages rise, so do those of the farmers left behind—more and better land is now available for them to work. This is why the Black Death raised living standards for the survivors. Under the circumstances, taxing farmers to subsidize manufacturing—as the United States did with its protective tariffs in the 19th century and as China does today with its currency manipulation—can make sense. As long as you can get the industrial share of the workforce growing faster than the rural population, this is a potentially win-win dynamic. But an economy like ours cannot take advantage of that. Taxing the service sector to subsidize manufacturing is just a straight transfer—and a poorly targeted one at that. For better or for worse, all advanced countries—even mighty Germany—employ the majority of their workers in the service sector.

The basic premise of the Obama tax reform proposal is that a less loophole-ridden business tax code can raise more revenue while doing less to distort economic activity. That is a sound argument. That framework should help accelerate economic growth while giving the government revenue it needs to invest in education, infrastructure, and other human services. But special manufacturing subsidies are an unfortunate exception to that fundamental logic, and Congress should reject them.