The first part of this series described how growing income disparities have made it more expensive for middle-income families to achieve many basic goals, such as sending their children to a decent school. Today’s installment discusses the forces that have caused income disparities to grow in recent decades. This essay is adapted from Robert H. Frank’s recently published book, The Darwin Economy.

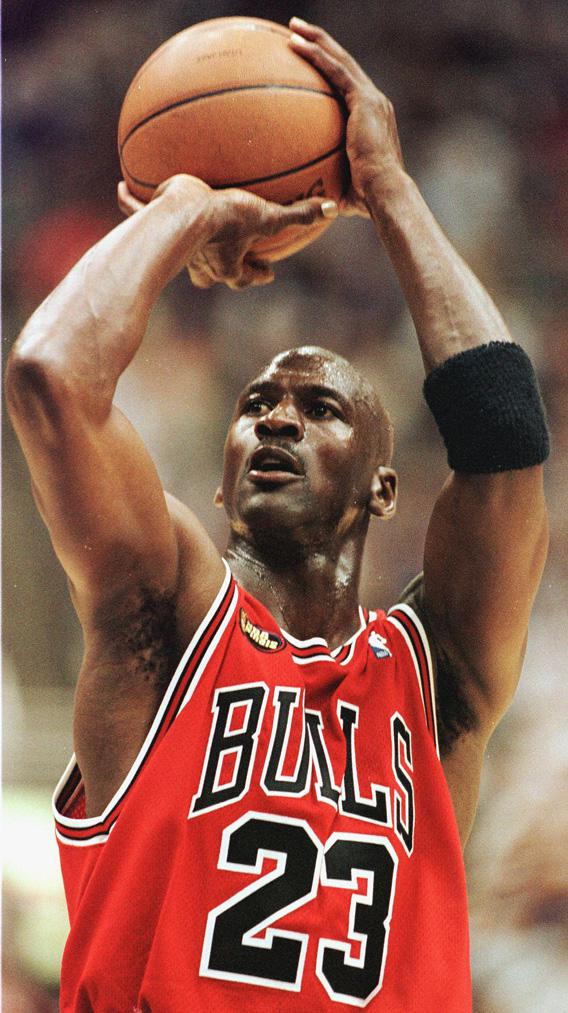

Photograph by Jeff Haynes/AFP/Getty Images.

Effective remedies for growing income disparities require a clear understanding of the forces that have caused them. In their recent book, Winner-Take-All Politics, Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson have argued that explosive salary growth at the top has been fueled by a more lax regulatory environment purchased with campaign contributions. That’s a spot-on description of what happened in the financial services industry, which is of course the principal target of the OWS movement.

But it’s an unsatisfactory account of why inequality has been rising in other occupations. The same pattern of income growth we’ve seen for the population as a whole has been replicated for virtually every subgroup that’s been studied. It holds for dentists, real-estate agents, authors, attorneys, newspaper columnists, musicians, and plastic surgeons. It holds for electrical engineers and English majors. And in none of those instances has it been primarily the result of regulatory favors.

To be sure, executives sometimes pack their boards with cronies who reward them with exorbitant salaries and bonuses. But such abuses are no worse now than they’ve always been. On the contrary, improved communications and falling transportation costs have almost certainly made them less serious. Executive hiring committees may not be perfectly informed, but they have more information than they used to, and this makes reputation a more effective predictor of performance. Similarly, increased vigilance from institutional shareholders and growing threats of hostile takeovers have placed additional constraints on executive pay abuse.

Despite these advances, corporate governance remains imperfect. But although there will always be cases in which mediocre executive performances are rewarded with high salaries, those who fail to deliver generally get the ax more quickly than in the past.

In our 1995 book, The Winner-Take-All Society, Philip Cook and I argued that top salaries have been growing sharply in virtually every labor market because of two factors—technological forces that greatly amplify small increments in performance and increased competition for the services of top performers.

Pay by relative performance is one defining condition of what we call a winner-take-all market. A second is that rewards tend to be concentrated in the hands of a few top performers, with small differences in talent or effort often giving rise to enormous differences in incomes. Both features show up in Sherwin Rosen’s description of the market for classical musicians:

The market for classical music has never been larger than it is now, yet the number of full-time soloists on any given instrument is on the order of only a few hundred (and much smaller for instruments other than voice, violin, and piano). Performers of the first rank comprise a limited handful out of these small totals and have very large incomes. There are also known to be substantial differences between [their incomes and the incomes of] those in the second rank, even though most consumers would have difficulty detecting more than minor differences in a “blind” hearing.

The enormous leverage of the most talented musicians was made possible by the development of breathtakingly lifelike recording and playback technologies. Now that most music we listen to is prerecorded, the world’s best soprano can be literally everywhere at once. And since it costs no more to stamp out compact discs from her master recording than from the master recording of any other singer, millions of us are each willing to pay a few cents extra to hear her rather than other singers who are only marginally less able. The upshot is that the best soprano lands a seven-figure recording contract while only marginally less gifted performers struggle to get by.

The same logic holds in the market for leaders of large organizations. The trustees who recruited David J. Skorton as Cornell University’s 12th president in 2006 knew that his most important responsibility would be to head the university’s $4 billion capital campaign, which was then just getting under way. The hiring committee identified several candidates they felt would succeed in reaching that goal. They eventually decided, however, that none could have handled the task nearly as well as Skorton.

Having seen him in that role for the past several years, I find it easy to see why. Skorton, a man of great humor, warmth, and charm, is a distinguished research cardiologist and an accomplished jazz musician. Alumni adore him. If his compellingly articulated vision of the university’s future persuades them to donate only 3 percent more than the next-best candidate would have, he will have boosted the university’s endowment by more than $100 million.

I don’t know how much Dr. Skorton is paid. But many social critics expressed shock and outrage when it was reported that annual salaries of presidents of some private universities had passed the $1 million threshold several years ago. Leaders of David Skorton’s stature are in short supply, however—and because they’re so valuable, the real surprise is that they’re not paid even more.

Vastly larger sums are at stake in many private companies. Consider a company with $10 billion in annual earnings that has narrowed its CEO search to two finalists. If one would make just a handful of better decisions each year than the other, the company’s annual earnings might easily be 3 percent—or $300 million—higher under the better candidate’s leadership. So if the top contenders for the CEO position are distinguishable with respect to the quality of the decisions they’re likely to make in office, then the competitively determined salary of the best candidate can be dramatically higher than that for the second best, even when the estimated difference in their talents is small.

Both the scale and scope of individual markets have grown enormously in recent decades. If one seller’s offering is better than all others, buyers from around the world now quickly get word of that fact. Lower shipping costs, coupled with falling trade barriers, have made it easier than ever to serve buyers everywhere. If an economic opportunity arises anywhere in the networked world, ambitious entrepreneurs are able to discover and exploit it more quickly than ever.

More intense competition has also been fueled by a significant increase in mobility. In the not-so-distant past, about the only way to become a CEO was to have spent one’s entire career with the company. With only a handful of plausible internal candidates, pay was essentially a matter of negotiation between the board and an individual who had no attractive prospects outside of the company. Increasingly, however, hiring committees believe that a talented executive from one industry can also deliver top performance in another.

A celebrated case in point was Louis V. Gerstner Jr. Having produced record earnings at RJR Nabisco, he was hired by IBM, where he led the computer giant, then struggling, to a dramatic turnaround in the 1990s. This new spot market for talent has affected executive salaries in much the same way that free agency affected the salaries of professional athletes in recent decades.

Greater competition also creates positive feedback effects that amplify the growth of salaries at the top. Such effects appear to help explain growing inequality among dentists, for example. Those whose earnings have grown most dramatically are often specialists in cosmetic dentistry, the demand for which has been fueled by higher top salaries in other occupations. And the highest paid dentists in turn often demand the services of the most highly paid specialists in other fields.

To be sure, the forces that have produced these changes have created important benefits for consumers. Tax software for the masses, for example, may have cost local accountants a lot of business, but it has also saved consumers an enormous amount of time and money.

Notwithstanding these benefits, the resulting growth in income inequality has exacted a high toll. Is there anything we can do to lessen it?

Tomorrow: Remedies for rising income inequality.