When he was a boy, Dr. Ben Carson used to accompany his mother to the mansions she cleaned. She’d ask him where he would rather live: This stranger’s big house, or their tiny flat near the railroad tracks in Southwest Detroit.

“You know the person who has the most to do with determining where you live?” she asked her son. “It’s you. It’s not somebody else; it’s not the environment.”

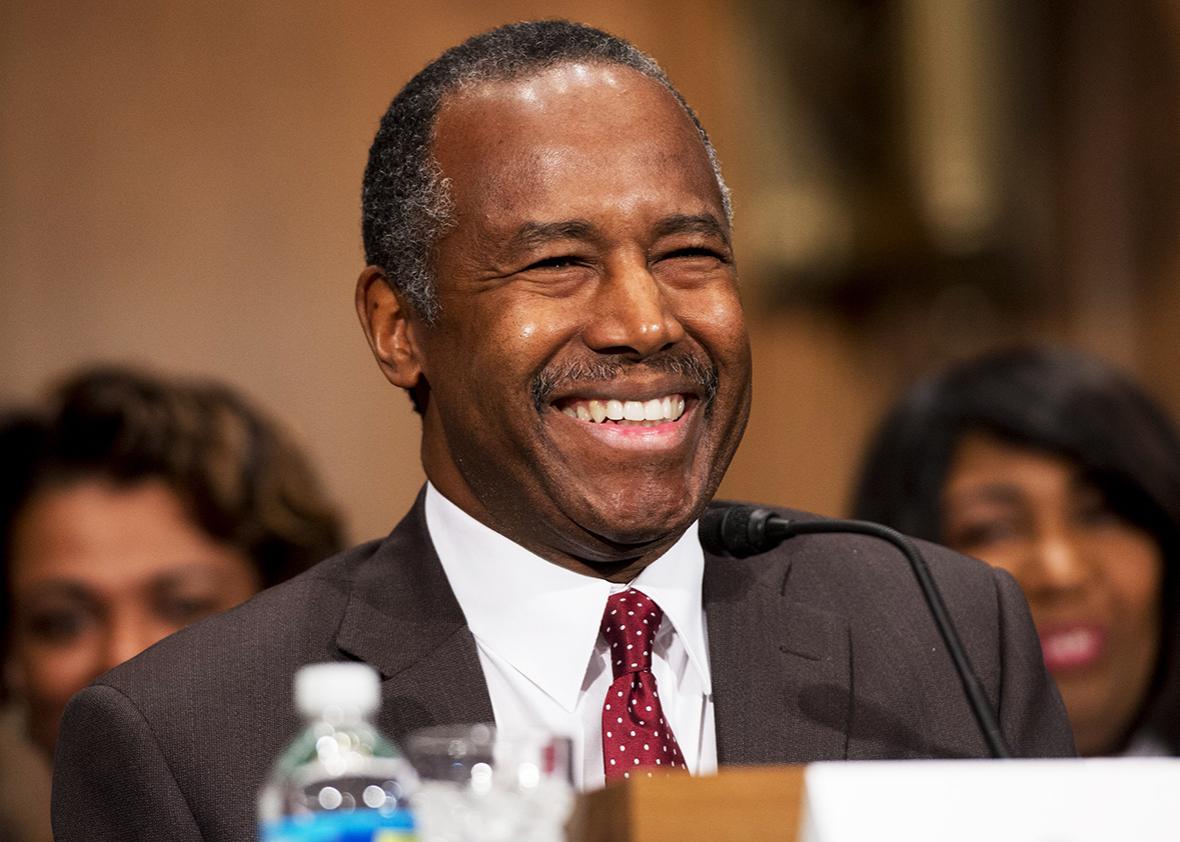

Carson told that story on Thursday morning on Capitol Hill, where he is being considered for the job of secretary of housing and urban development under President-elect Donald Trump. It was a perfect sketch of just how bad a candidate he is for the job, which was created to combat exactly that dangerous, persistent lie: that as an American, you may live wherever you please.

Carson’s remarkable personal history—from welfare in Detroit to Yale College to the head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins—has been touted as his preeminent qualification for the nation’s top housing job. “I understand housing insecurity,” he said, and surely he does. But his ascent has given him a blinkered view of the power of talent, ingenuity, and gumption. (And endeared him to white Republicans in the process.)

I can’t blame Carson’s mother for giving her son a hopeful message. But I will blame Carson for invoking it now as some timeworn pearl of wisdom as he prepares to take the reins of the $47 billion department.

There’s no aspect of American life that refutes that myth of radical individualism as surely as housing. In 1956, when Carson was 5, the mayor of Dearborn—a suburb a few miles from his house—boasted of the town’s reputation for whiteness. “Negroes can’t get in here,” he said. “Every time we hear of a Negro moving in, we respond quicker than you do to a fire. That’s generally known.” The same year, in Royal Oak Township, a tiny enclave between the Detroit Zoo and 8 Mile Road, a black secretary who worked for the local school board was tied up and beaten in her home by white men in masks.* Black homebuyers in the suburbs were occasionally met by rock-throwing mobs, and most didn’t risk it. In 1968, the year Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, which directed HUD to “affirmatively further” fair housing, there were no black homeowners in Dearborn. There was one in Livonia. There were four in Warren, a city whose population hit 179,000 in 1970.

We knew going into Thursday’s hearing that Carson had the optimistic view of human potential you’d expect from a man who fixed brains for a living. “Poverty is really more of a choice than anything else,” he once told a TV interviewer. He has spoken harshly of the “culture of dependency” fostered by the social safety net. Advocates have feared that Carson would be philosophically ill-suited for the job, and practically ill-equipped, having no experience in government or housing policy.

But what stood out at his hearing today was how fundamentally uninterested Carson seemed to be in the role that housing—its condition, cost, geography, and availability—plays and has played in American life. His official, written remarks submitted to the committee were full of insight and expertise. But it turned out most of the text had been copied from newspaper articles and think-tank reports. In his spoken testimony, he took every opportunity to turn the conversation somewhere else.

He talked about the emphasis he liked to place on education and health care. He talked about tax reform, trade reform, regulatory reform. He talked about “fixing our economy” and “being cognizant of our fiscal responsibilities” and “creating an environment that encourages entrepreneurial risk-taking and capital investment.” At times, it sounded like he thought he was still running for president.

Carson did not sound like the fiercely critical observer who had written, in the summer of 2015, about disparate impact, subsidized housing in wealthy areas, and suburban segregation. That Ben Carson railed against Obama HUD Secretary Julian Castro’s “government-engineered attempt to legislate racial equality.”

Since that was, until Thursday, Carson’s only public statement about federal housing policy, and since Donald Trump’s plan for the American city does not mention housing, he was asked about it almost immediately by Sen. Sherrod Brown, an Ohio Democrat.

The problem, Carson responded unconvincingly, was with “one-size-fits-all, cookie-cutter” solutions. That’s exactly what the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule is not: On the contrary, it requires communities to assess their own housing profiles for evidence of discrimination.

That exchange was typical. Carson didn’t emerge as a radical; on the contrary, he seemed to shift for each questioner, telling North Carolina Sen. Thom Tillis that no department program was a “sacred cow” after assuring Hawaii Sen. Brian Schatz that he’d be an advocate for the HUD budget.

Carson’s response to Schatz somehow managed to be both his most substantive of the day and the one that best distilled his daylong mien of a student fumbling through an oral exam. He would undertake a “listening tour,” he said, and then put together a “world-class plan.” “I want to come to you with that world-class plan, and I want to convince you all that is what we need to do,” the neurosurgeon said. “I don’t know what that number is going to be—it might be quite frankly, it might be more, it might be less, but it will be what is required to accomplish what we need to do.”

Experience, of course, has not been a guarantee of good stewardship. George W. Bush’s housing secretary, Alphonso Jackson, had headed housing authorities in Dallas, D.C., and St. Louis, but pushed to ease terms on subprime mortgages and wound up resigning amid allegations he had used his position to punish the Philadelphia Housing Authority for “refusing to transfer property to one of [his] friends.” (It is easy to see how an even more fraught situation might reoccur in the administration of a developer-president.)

What Carson needs to do is help poor tenants handle the systemic, nationwide mismatch between low wages and high rents. Hopefully someone will tell him that on his listening tour.

*Correction, Jan. 19, 2017: This article originally misstated the location of the Detroit Zoo. It is in Royal Oak, not Royal Oak Township. (Return.)