If you think Detroit’s population decline has been bad—the city had 1.85 million residents in 1950 and just 710,000 in 2010—consider the total disintegration of its transit network. At the end of World War II, Motown and its environs were home to the largest municipally owned streetcar system in the United States. Regional streetcars, buses, and commuter rail counted an annual ridership of 490 million.

Today, the streetcars and commuter rail are gone. Until a new streetcar line opens next year, Detroit will be the largest American metropolis without surface rail transit. The annual ridership on urban and suburban transit is now 36 million, a decline of more than 90 percent from its 1940s peak. The entire city of Detroit has lower weekday bus ridership than the two busiest individual New York City bus routes.

It’s not for lack of need that the region doesn’t support transit: Despite its autocentric reputation, Detroit is eighth nationally in its percentage of carless households—behind the nation’s transit capitals of New York; Washington, D.C.; Boston; San Francisco; Chicago; and Philadelphia; as well as Baltimore. The region spends $69 per capita on transit each year; for comparison, Atlanta spends $119 per capita, Cleveland $177, and Seattle $471.

The Detroit area’s shambolic system is a burden on residents who can’t or don’t drive. Last year, a Detroit factory worker named James Robertson became a local celebrity after the Detroit Free Press wrote about the daily 21-mile commute he made on foot. They called him the “Walking Man.” A local car dealer gave Robertson a brand-new Ford Taurus, and now he drives to work. The remaining 66,000 households that make up Detroit’s carless population aren’t so lucky. For them, no bus means no way to get to work, or anywhere else. Poor transit access is linked to unemployment, low income, and low economic mobility.

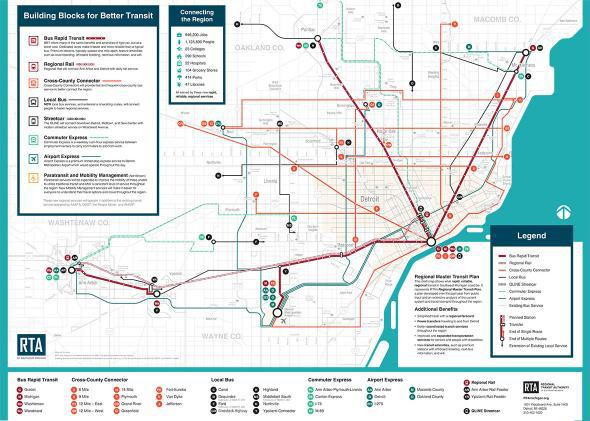

But America’s worst transit system could be getting better soon. Last week, the Southeast Michigan Regional Transit Authority, or RTA, unveiled a $4.6 billion plan to knit Detroit, its suburbs, the Wayne County Airport, and the nearby college towns of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti into one comprehensive network. The Regional Master Transit Plan, or RMTP, would bring integrated transit to the Detroit region for the first time in more than 50 years and solve longstanding problems of transit funding and governance through a mandatory transit millage, or property tax increase, of $120 on every $100,000 of assessed value. Following a public review period this month and RTA board approval in July, the proposal will face an up-or-down vote on the ballot this November across four counties of southeast Michigan.

Screenshot via RTA Michigan

If it passes, the plan would double per capita transit funding in the region—and represent a rare instance of cooperation in the vitriolic political history of mostly black Detroit and its largely white suburbs. Its approval would signify popular recognition that Detroit and its surrounding counties share a common interest. And it would make it a whole lot easier to get around without a car.

The status quo, in contrast, is encapsulated by the infamous pronouncement that L. Brooks Patterson, the executive of wealthy Oakland County to the north of Detroit, made to the New Yorker in 2014: “I made a prediction a long time ago, and it’s come to pass. I said ‘What we’re going to do is turn Detroit into an Indian reservation, where we herd all the Indians into the city, build a fence around it, and then throw in the blankets and corn.’ ”*

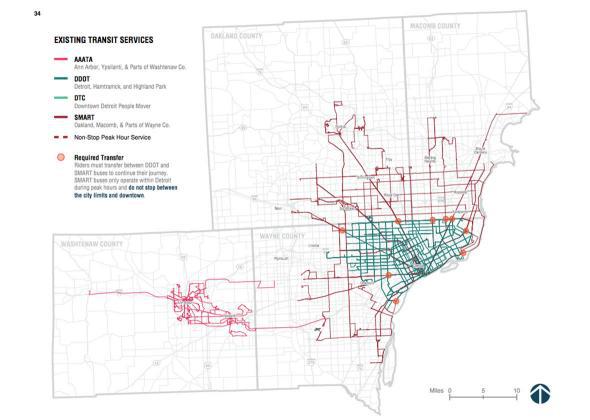

For Detroit bus riders, 8 Mile Road might as well be that fence. Detroit routes, shown in green on the map below, stop abruptly at the city limits; the buses that roll through the streets of the wealthy northern suburbs don’t generally cross 8 Mile Road. Those that do make the trip to downtown Detroit are forbidden by an old city ordinance from picking up passengers inside the city lines in the morning or dropping them off in the evening. (And few of the urban or suburban buses come more than once every half-hour, even during the morning rush.)

Screenshot via RTA Michigan

Such parochialism wouldn’t make sense anywhere in America, but it’s particularly inane in Detroit. Three in 5 Detroiters work outside the city, and nearly three-quarters of the people who work inside Detroit live in the suburbs. According to the Brookings Institution, only five U.S. metros—the Sun Belt boomtowns of Atlanta, Dallas, Phoenix, Houston, and Nashville—have longer typical commute distances than Detroit’s 10.4 miles. The economies of city and suburb have always been interdependent, even as their transit systems have remained stubbornly apart.

The RTA plan would fix that. It proposes bus rapid transit, or BRT, corridors on Detroit’s wide, radiating avenues that would take passengers from downtown Detroit to Mt. Clemens, Pontiac, Dearborn, and the airport. It would reopen a long-closed commuter rail link between Ann Arbor, home of the University of Michigan, and Detroit. And it would extend a grid of 11 “cross-county connectors” (high-frequency local buses, essentially) across the region.

“There’s a growing realization in the city and the suburbs that we’re really one economy,” argues Sandy Baruah, CEO of the Detroit Regional Chamber, an economic development organization that has been closely involved in the RTA plan. “What happens in the suburbs is what happens to the city and vice versa. The economic crisis really showed that no place is an island. We’re going to thrive together, or we’re going to sink together.”

That has not, historically, been the consensus in the Detroit area. And the transit networks have reflected it.

The fragmentation of transit began in 1956, when the last streetcars were replaced by buses that wound up under the dueling authority of the Detroit Department of Transportation and the suburban agency, now called SMART. Neither body had the funding to maintain post-war service levels. In the suburbs, public support dwindled amid racial tensions over busing and school integration. At planning meetings, white suburbanites railed against transit, which they feared would bring in “undesirables, transit crime and low-income housing,” the Detroit News reported. And the city, under Mayor Coleman Young’s two-decade tenure from 1974 to 1994, didn’t want to surrender control to an agency dominated by suburban politicians.

The transit history of the region is cluttered with remedial acronyms: 1969’s Detroit Regional Transportation and Land Use Study; or TALUS, 1984’s Regional Public Transportation Consensus Plan, or RPTCP; 1989’s Regional Transit Coordinating Council, or RTCC; 2001’s Detroit Area Regional Transportation Authority, or DARTA. The best that more than a dozen attempts could do for the region was create a cross-agency bus pass. Their failures are more remarkable. In the 1970s, southeast Michigan forfeited President Gerald Ford’s promise of hundreds of millions in federal dollars for regional transit because leaders couldn’t compromise on how the money should be spent.

The RTA, created by Gov. Rick Snyder in 2012, might actually make a difference. Unlike its early-’00s predecessor DARTA, it has the power to levy taxes throughout the four-county region. If its transit plan passes this November—when voter turnout in these blue counties will be high—it will collect a transit millage from a big swath of the state. And unlike the suburban SMART, it won’t allow anti-transit municipalities to opt out of the service region—a feature that has drained support from regional bus operations and produced a transit coverage map that looks like Swiss cheese.

Does the Regional Transit Master Plan stand a chance with voters? It’s only been a week since the draft plan was released in full, but some of the ideas have been discussed for years, and many supporters feel optimistic. The fracture between Detroit and its suburbs is deep—but in some ways, not as deep as it has been before. The share of Detroiters living in predominantly white suburbs, for example, fell from 65 percent in 2000 to 49 percent in 2010. Transit millage for SMART bus service is consistently, resoundingly renewed by suburban voters (in communities that have opted into the SMART service area). And Detroit, riding a wave of good press and downtown growth, is seen as more of a regional asset than it used to be.

“The fundamental difference between now and even five years ago is that Detroit is rapidly becoming a city that the region can be and is proud of,” says Baruah. “That’s really changing the dynamic. The resurgence, the businesses moving in, the good government—all those good feelings about the city they grew up in, feelings that may have gone away 20 years ago, are starting to come back.”

Detroit, where more than a quarter of households don’t have a car, will likely vote in favor. The college towns of Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, where many voters don’t own property, have been promised quick, cheap, carless access to downtown, which may be enough of an enticement to win widespread support for the RTMP. Transit to the airport, in the form of five hourly airport express buses, is a carrot for wealthier voters.

Still, the result will come down to suburbanites. Their politicians haven’t exactly been enthusiastic. Macomb County executive Mark Hackel has very cautiously expressed support for the plan but voiced concerns about the tax burden. Patterson, the Oakland County executive, supported the creation of the RTA in 2012 but hasn’t taken a position on the referendum. Gerald Poisson, a deputy of Patterson’s, observed in an interview with Bridge magazine earlier this year that a millage of 1.1 would bring in just $7.7 million from Detroit—and $57 million from Oakland County, whose population is not even twice that of Detroit. (The actual RTMP millage is 1.2.)

To some extent, the routes are well-positioned to draw out voters in the suburbs, explains Tiffany Gunter, the Deputy CEO of the RTA. Good transit follows residential density, so the benefits of the plan should be close at hand in the more highly populated areas of the region.

In this case, transit also follows money. The Michigan legislature gave the RTA an “85 percent” rule that requires most money to be spent in the county where it’s collected. As a result, the network must, by law, replicate in its service provision some of the disparities that exist between urban and suburban wealth in the region. Nevertheless, it will constitute in a small way the kind of suburb-to-city wealth transfer that residents of the Detroit suburbs have long found undesirable. It also affirms downtown Detroit’s regional prominence, though no metro area in the U.S. has a smaller share of jobs within three miles of the central business district.

Joel Batterman, the coordinator of the Motor City Freedom Riders, an organization that advocates for better transit in the region, believes that anti-transit politicians are a step behind. “Shutting people out of opportunity and trashing the central city is ultimately suicidal for everyone in the region, even the affluent suburbs,” he says. “Some inner suburban leaders are recognizing that transit is critical for their communities to prosper. I’m afraid that hasn’t filtered up to county-level leadership, but even there we see some beginnings of change.” Corporate support for transit, from the area’s big foundations as well as business organizations like the Detroit Regional Chamber, has been strong.

*Correction, June 7, 2016: This article originally misquoted Oakland County Executive L. Brooks Patterson’s quote to the New Yorker. (Return.)

Until November, that is, when buses, trains, and property taxes go on the ballot. The plan’s passage would break down some symbolic barriers, and some practical ones as well.