A quest to remedy poverty has animated a certain cross section of American society since Jacob Riis took his camera and flash bulb into the dank tenements of Manhattan and produced How the Other Half Lives in 1890. Let’s call this cross section the liberal establishment.

In addition to exposing the deplorable living conditions of the poor, Riis also stoked public fears of poor neighborhoods being hotbeds of immorality. In the decades after it first glimpsed this urban poverty in Riis’s photographs, the liberal establishment watched as metropolitan areas around the country grew ever more segregated. By midcentury, with the aid of myriad government programs, the Other Half completed its metamorphosis from a multiethnic to an almost exclusively black urban underclass. The liberal establishment knew that segregation and poverty were inextricably linked, but its well-meaning fight against segregation remained hindered by racism that persists beyond the letter of the law.

Today, fewer Americans live in poverty than did in 1950, but the rate of extreme poverty, in which families live on less than $2 per day, has risen by 159 percent since the mid-1990s, according to one recent study. More than a fourth of black and Hispanic people in the country live in poverty, and most black people live in majority black neighborhoods where overall poverty rates tend to be much higher, no matter the income of the individual. Part of the liberal establishment’s failure to address this problem stems from its inability to embrace truly progressive understandings of poverty. Those advocating for solutions to poverty rarely speak about the way our economy and social infrastructures entrench it. Rather, much of liberals’ efforts have been crippled by unexamined and unchallenged beliefs that the spaces where poor people of color live are morally compromised, beliefs summed up by one well-intentioned but ultimately damaging term: concentrated poverty.

Hoping to combat concentrated poverty, the liberal establishment has championed policy initiatives aimed at breaking up these census tracts where more than 40 percent of residents live below the poverty line. Much of the language of scholarly articles and policy briefs emphasizes that poor people of color living together do not have access to the kind of power necessary to give their children better futures. Journalists, too, continue to imply that it is natural for concentrated-poverty neighborhoods to have bad schools, that the poor services stem from the poor economic conditions. In effect, rather than untangling the complicated causes of concentrated poverty, the liberal establishment blames concentrated poverty for the poor educational attainment of children and deficient child-rearing practices of adults. But this is a dangerous conceptual trend, because it validates the idea that wealth and power go hand in hand and that poverty, not an array of structural problems, is to blame for the disadvantages of being poor.

It is for this reason that we might cheer last month’s Supreme Court decision in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. the Inclusive Communities Project, holding that the Federal Housing Act allows for lawsuits based on so-called disparate impact claims—while realizing that it is not nearly enough. With the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the federal government was obligated to not only combat residential segregation but also to actively promote integration. For the past 50 years, however, the FHA has largely been ignored or subverted by local governments, and federally led desegregation efforts have been forsaken. The court’s ruling means that minority groups and individuals do not have to prove any actor’s intent to discriminate, only that housing practices—from renting to mortgage loans to tax credits for low-income housing development—in their communities prevent them from leaving minority neighborhoods. In theory, the court just gave activists an important tool for breaking up concentrated poverty.

Nevertheless, we should remember that disparate-impact claims remain extremely difficult to make because gathering the necessary data is expensive and time-consuming. Far from ending discriminatory housing practices, the latest decision only helps ensure that, for now, one avenue for litigation against them remains open and may one day help some people move. Despite its significance, the Supreme Court decision highlights the ineffectiveness of current solutions for segregation, which are tied to how federal and local elected officials, informed by liberal think tanks such as the Brookings Institution and the Urban Institute and countless liberal policy groups, think about poverty. If we want to make a dent in this problem, we should re-examine the terms in which we speak about it. We can start by tossing out concentrated poverty.

* * *

Since the 1960s, some in the liberal establishment (and many in the conservative one) have believed that a certain “culture” among black Americans predisposes them to poverty. To live in poor black communities, surrounded by this “culture,” is to condemn oneself and one’s children to downward mobility. This idea has its roots in 19th-century social Darwinism, but it resolutely became a matter of government policy and political speech 50 years ago, when then–Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan published The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.

The report claimed that urban black Americans were caught up in a “tangle of pathology.” Unwed motherhood and unemployment led to intergenerational delinquency and alienation—a mindset that kept poor black people stuck in place. Moynihan’s report also indirectly assured white Americans that the problems of the black ghetto were not their fault.

Though in some dissenting, academic corners of the liberal establishment, Moynihan’s characterizations of the poor were duly recognized as racist stereotypes, his observations spurred the War on Poverty—a set of sweeping new laws that gave America food stamps, social security, guaranteed funding for primary and secondary education, and new jobs programs.

And yet, despite this federally funded bounty, the black ghetto persisted. In fact, life there got worse as the 20th century drew to a close. In 1987, sociologist William Julius Wilson published The Truly Disadvantaged, a seminal study in which he coined the term concentrated poverty to describe poor urban neighborhoods.

“Concentrated poverty”—which Wilson described as wreaking havoc among black Americans in the same ways as Moynihan’s “tangles of pathology”—quickly caught on with the liberal establishment, becoming the focus of poverty studies and policy initiatives in recent years.

“Concentrated poverty” disproportionately befalls black Americans, and not even the deepest white poverty can compare. The term is shorthand for saying that we aren’t just talking about people of little means but about a systematic lack of basic resources across very specific areas. They comprise voids across America’s census tracts, where schools, jobs, police protection, banks, grocery stores, and hospitals greatly diminish in quality or simply disappear. This deprivation is so severe that its effects are nearly impossible to escape from generation to generation.

But this useful shorthand also cuts off the conceptual blood supply between cause and effect. When we blame “concentrated poverty” for the diminished quality of life in minority neighborhoods, we are confusing that which creates poverty (namely racist policies and practices) and the conditions created by it.

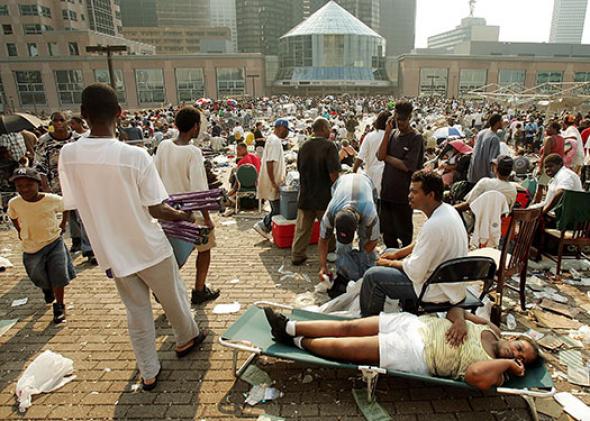

An example of this conceptual confusion came days after Hurricane Katrina made landfall. Speaking on Sept. 15, 2005, as New Orleans began to recover, Democratic New York Rep. Charles Rangel (a liberal) praised David Brooks (not a liberal) for his column “Katrina’s Silver Lining” on the House floor.

Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images

“Poverty was the underlying cause of the tragedy that occurred in Louisiana a couple of weeks ago,” said Rangel. He continued that people’s poverty prevented many from escaping the flooding city and that Katrina provides a chance to eradicate that poverty.

This seems innocuous enough. Only now, almost 10 years later, is it apparent that to blame poverty for the fact that so many poor people did not receive adequate or timely help is circular at best. And we know that Katrina did not lead to the eradication of poverty, which persists in that city despite the disaster. Rather, it provided a chance to remove some of the poor.

Brooks’ column, which characterized poor New Orleanians as uneducated criminals, inept mothers, and immoral womanizers, and which Rangel read in its entirety for the Congressional record, is a conceptual poisoned apple. In 750 words he connects the directive to “break up zones of concentrated poverty,” so attractive to the liberal establishment, to racist, pathological, Moynihanian stereotypes about black Americans.

On Rangel’s lips, Brooks concludes that it was a blessing for poor black residents of New Orleans to lose their homes. This way they couldn’t come back and live their collective pathologies together again.

In the wake of Katrina, affordable housing was not rebuilt in the city, and some public housing was eliminated. The public school system disappeared too, leading to the creation of the first all-charter school district in the nation. All this has made the city less accessible to poor people of color. In 2012, more than 100,000 fewer black Americans resided in New Orleans than in 2000.

Non-hurricane-inspired solutions to the problems of concentrated poverty have long fallen into two camps: investing in such communities to raise living standards or moving poor minorities out to communities that are whiter and already enjoy those standards. Neither of these projects, in their limited implementations since the War on Poverty began, have been able to desegregate and deghettoize, likely because they target the symptoms and not the causes of poverty. The mobility programs in particular have done nothing to challenge the processes through which black spaces in this country have become unlivable.

The new Supreme Court decision will allow more minorities to move into wealthier, whiter communities, thus gaining access to the socioeconomic benefits of life therein. But housing mobility efforts, while beneficial for some individuals, only affirm the notion that there is something inherently wrong with black communities, that it is inevitable for them to be cut off from opportunities, and that to live a better life, black people either have to move out of their neighborhoods or white people have to move in.

The court’s ruling is based on a case in which tax credits for low-income housing in Texas were allocated to poor, minority neighborhoods at disproportionally higher rates than to better-off white ones. This is exactly how public housing ghettos came to be decades earlier, when projects were built only in the poor, black neighborhoods from which their residents came. While it is commendable that the court recognizes the right to sue if tax-subsidized affordable housing does not appear outside of poor neighborhoods, another result of this decision could be a slowing or halt of affordable housing construction in Texas altogether, just as in the 1970s Chicago stopped building public housing after the Court said it had to build it in white neighborhoods, too. This is because this ruling, like the ones before it, does nothing to destigmatize blackness or poverty.

Until now, the fight against “concentrated poverty” has essentially been a fight to give some poor people a chance to leave their neighborhoods. It has not been a fight against the behaviors of individuals, businesses, and governments that place innumerable hurdles in the path of a poor person of color trying to live a good, healthy, safe life.

Concentrated poverty is not the cause of these hurdles; it is what happens when people get so exhausted that they cannot keep jumping. It is the legacy of discriminatory housing policies that deplete the tax bases of black neighborhoods. It’s the predatory lending that creates debt rather than equity for black families. It’s the budget cuts to schools in these neighborhoods that cause higher dropout rates. It’s the erosion of full-time employment and benefits that causes the growth of elicit economies and racism in the criminal justice system that cuts off young black men from prospects of normal lives. Every one of these factors and more are tributaries trickling into concentrated poverty, and every one of them springs from decisions made by those in positions of influence and authority.

There is little hope for a meaningful solution to the problem of concentrated poverty until the liberal establishment decides to focus on untangling a different set of pathologies—those inherent in concentrated power, concentrated whiteness, and concentrated wealth. We have seen these pathologies play out on national television more and more frequently since the fatal shooting of Michael Brown last summer. Just a few days before a white supremacist shot nine black people in a South Carolina church, these pathologies revealed themselves in the arrests of black children at a McKinney, Texas, pool party. Before local police officers made their infamous intervention, white residents from the neighborhood shouted at the kids to go back to Section 8 housing where their black bodies presumably belonged.