Like Chumbawamba, Canadian-born tech entrepreneur Stewart Butterfield gets knocked down but gets up again. Butterfield was the co-creator of the first real Internet photo-sharing service, Flickr, a viral success that Yahoo acquired for a reported $35 million in 2005. More recently, his new startup Slack, which makes team communication software, raised over $40 million in funding. But just as Chumbawamba’s danceable “Tubthumping” came as a surprise turnaround from a onetime noisy punk band, both Flickr and Slack were successful pivots from other projects that were doomed to failure. Both times Butterfield and his cohorts salvaged a nugget from the original venture and made it the center of a successful new one.

In 2008, having spent three years with Yahoo after the Flickr acquisition, Butterfield left with this memorable resignation letter: “I will be spending more time with my family, tending to my small but growing alpaca herd and of course getting back to working with tin, my first love.” The letter belied his subsequent project, which in fact had little to do with tin but was rather an online multiplayer game called Glitch.

Courtesy of Nina Kang

With no combat and only secondary questing, the game focused on crafting, curating, and socializing. Though superficially akin to Second Life, the game did not focus on monetization or an in-game economy, but on a quirky, homegrown aesthetic that attracted a small but fervent following. Players explored a surreal environment that ranged from fairy-tale to futuristic to horrific. User avatars were vaguely humanoid multicolored gnomes. (Inanimate garden gnomes frequently served as butlers.) Miyazaki-esque “Street Spirits” sold items that could be combined and transformed to create assorted creative and bizarre objects. Users created their own little strange boutiques and curated museums of eggs and strings, threw parties, and devoted themselves to 11 animistic deities, from Humbaba the Walker to Alph the Creator.

Courtesy of Nina Kang

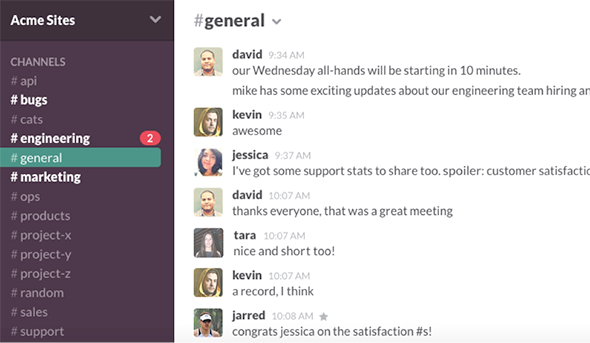

The game’s invented pantheon and Magritte-influenced backdrops did not attract enough of an audience to draw sufficient financial backing, and Glitch closed down in 2012. (Some of the players are trying to resuscitate it.) “It was so weird and unfamiliar to people,” Butterfield said to Pando. But during the development of Glitch, Butterfield’s team had written a collaboration tool; because the team was geographically distributed all over North America, most communication was not face-to-face but online. While they initially chatted via Internet Relay Chat, or IRC, it simply didn’t scale as the team increased to dozens of people. After Glitch shut down, Butterfield told me, “One thing we were sure of was that we wouldn’t work without a system like that again, and we thought a lot of other companies would like to have such a system.” The day-to-day socializing during the process of making Glitch turned out to be the use case for a more successful product. Taking the basic Slack tool and extending it to a variety of platforms, Butterfield’s team at Tiny Speck built out a modern information-sharing environment that has already seen positive acceptance by BuzzFeed, Business Insider, Stack Overflow, the Guardian, and Lonely Planet.

Courtesy of Sirentist

Courtesy of Slack

Something very similar had happened before. Butterfield’s first startup was a multiplayer online game similar to Glitch, called Game Neverending, or GNE. Begun in 2002, GNE was an exploratory project that contained the seeds of much of what went into Glitch. Butterfield and his partners at Ludicorp, Caterina Fake and Jason Classon, intended GNE to be a dramatically extendable playspace where users could create their own objects and locations. But having built a prototype, they found that the post-dot-com crash world was the worst time in which to try to get a startup funded.

GNE was an ambitious project that was going to take well over a year to build, so they searched for a way to repurpose their existing work. Butterfield and the rest of Ludicorp had observed the growth of online socializing in the 1990s, but in 2003, “social networking” barely existed; Friendster had just been founded, Google bought Blogger only that year, and Facebook and Twitter did not yet exist. GNE tipped them off that the sorts of socializing that had previously been done on Usenet and IRC were becoming increasingly mainstream, and that discretionary time was going to shift from television to the Internet.

The niche Butterfield and his associates identified was picture sharing. At the time, there was no easy way to upload a picture and hotlink it, as you do with Imgur or Twitpic or a hundred other sites today, and there was no blogging service that made it easy to share pictures. So Ludicorp created Flickr as a photo-blog hybrid, the first online service of its kind. The model was that of a social network or blog: You could upload pictures, your friends could subscribe to them and see a stream of them, and comment on them.

As a project, Flickr was vastly simpler than GNE. Its success lay not in the sheer difficulty of the task but in the fact that GNE had led Ludicorp to identify a gap before the rest of the market. The speed at which they developed the product allowed them to fill that niche before anyone else could bring a product to market. Conceived in December 2003, Flickr launched in February 2004. It immediately took off, attracting a fervent following of professional photographers as well as those who just wanted to share family and social shots. “We caught a tailwind from more and more people coming online and starting to blog,” Butterfield said. After a year of constant updates driven by user feedback, the Yahoo acquisition came scarcely a year later.

Courtesy of Glitch

Glitch and Game Neverending were both unusual and visionary. Each time, the subsequent success lay in the extraction of a somewhat less ambitious project from within the original ambition. In the case of Glitch, which begot Slack, it came in the form of a communication tool that the development team needed to create the product in the first place. In the case of GNE, which begot Flickr, it came by observing how people were using the product and then finding a larger audience for it. Eccentric, creative failures are frequently incubators for what, in retrospect, seem to be the most practical of products. With Glitch’s devoted following still behind him, Butterfield has achieved the dream of many a writer and artist: a large audience, and a smaller, more fanatical cult audience.