The Oreo cookie turned 100 years old Tuesday. The simple, cream-filled confection has outlasted countless other baked goods. Why have Oreos been so popular for so long?

Marketing muscle, among other things. The early history of the Oreo suggests that the size and power of the National Biscuit Co. (now Nabisco) played a major role in the cookie’s dominance. The Oreo brand did not enjoy a first-mover advantage in the market for chocolate cream sandwich cookies. The Sunshine Baking Co. had begun selling the Hydrox sometime between 1908 and 1910, beating Oreos to store shelves by at least a couple of years. Sunshine was smart to commercialize the chocolate sandwich cookie, which had been a popular homemade treat in the United States since the mid-1800s, but the company never had much of a chance against National Biscuit—the Standard Oil of biscuit makers. The country’s largest bakeries joined to form the cookie monster in 1898, and the company modernized the production and packaging of baked goods. (Prior to that, most cookies and crackers were sold out of barrels at local shops, hence the name “cracker barrel.”) National Biscuit was soon selling half of America’s cookies and crackers, mostly out of its New York factory in the building now known as Chelsea Market. When the company launched Oreo in 1912, it had already succeeded with the Lorna Doone shortbread cookie. A major ad campaign quickly saw Oreo pass Hydrox, and it’s now widely regarded as the best-selling cookie of all time, although the Explainer is unaware of reliable data to verify the claim. In 1982, consumers spent 10 percent of their cookie dollars on Oreos, according to the 1985 Guinness Book of World Records.

There’s more to Oreo’s longevity than marketing, of course. National Biscuit also released the Mother Goose Biscuit (“a rich, high class biscuit bearing impressions of the Mother Goose legends,” according to company marketing materials) and the Veronese Biscuit (“a delicious, hard sweet biscuit of beautiful design and high quality”) with similar ad campaigns in 1912, but neither took off like Oreo. In a 1981 article titled “Creative Eating: The Oreo Syndrome,” folk historian Elizabeth Mosby Adler argues that part of the sandwich cookie’s appeal is that it allows people to bring their own personal style to eating. Like fried eggs, layer cake, and corn on the cob, the Oreo lets consumers make choices—they can gobble it whole, disassemble it, eat the best part first or save it for last. In contrast, there’s really only one way to eat a chocolate-chip cookie. Eating an Oreo can also be an addictive kind of challenge. It’s not easy to separate the wafers while leaving the frosting intact or to peel the frosting away in a single slab. Of course, if you fail, you can just try, try again. Eating an Oreo lets non-cooks participate in the creative aspect of food.

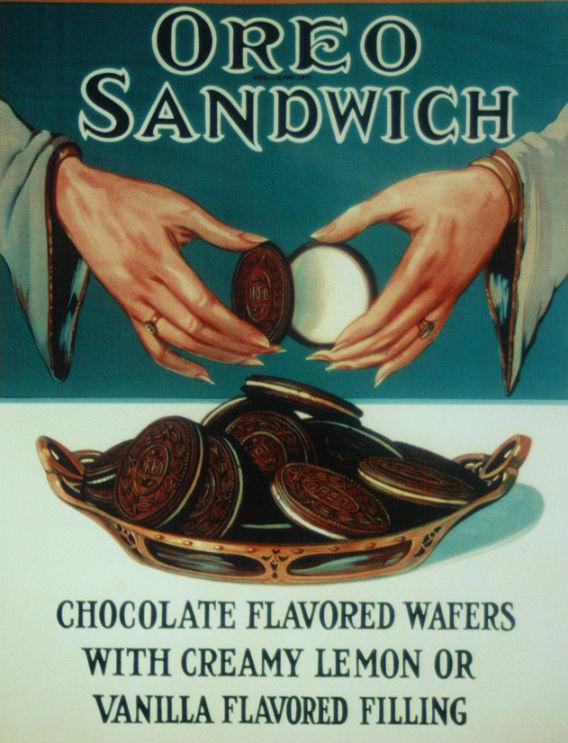

Aesthetics may also have helped Oreo along. Writing in the Atlantic last year, Nicola Twilley noted that the original design was more ornate, similar to the garden theme featured on the now-defunct Hydrox. The company adopted a simpler, more geometric look in 1952, with stamped edges and triangular shapes pressed into the cookies.

Then there’s the quirky name. The origin of Oreo is shrouded in mystery, but some believe the word derives from the Greek for hill. (An early version of the cookie was dome-shaped, according to legend.) Some in the industry seem to think the name is important. When Keebler acquired the maker of Hydrox in 1996, its marketing arm discovered that consumers didn’t like the cookie’s name. The company thought that a snappy new moniker might revive the perpetual also-ran. Executives considered Hydihos, Hydunks, Twisters, and Choco Twists before settling on Droxies in 1999. The change didn’t have the desired effect, however, and Droxies were discontinued in 2003.

In its day, Hydrox did dominate one sector of the market—Jews who keep kosher. Oreos contained lard until 1993. Nabisco eventually altered the recipe and obtained kosher certification in 1998, eliminating Hyrdox’s last significant toe-hold in the market. Some other products have recently grabbed segments of the market, like the Newman-O’s organic cookie.

Got a question about today’s news? Ask the Explainer.