In this five-part series, an American in Paris pits the French welfare state against the U.S. market economy in five key categories: childbirth and health care, preschool, higher education, immigration, and shopping. Read all the entries in the series here.

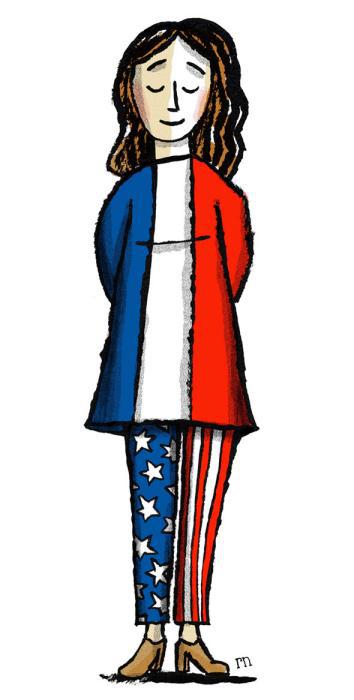

Illustration by Robert Neubecker

About nine months after I moved to Paris, I found myself in a government classroom near the outskirts of the city with a group of other immigrants to France. We were all there for our jour civique, a daylong class in French history and government that is mandatory for all applicants for a titre de sejour, France’s residency card. Instituted by former President Nicolas Sarkozy in one of his attempts to appear tough on immigration, the jour civique is designed to help foreigners integrate into the French legal and cultural system. I was the only American in this group, most of whom came from former French colonies or protectorates. As our teacher went through the specifics of France’s parliamentary government and its key laws, many of the students looked bored—they’d already studied this in school, and the whole thing had a whiff of colonialism about it.

I was more interesting to some of them than the class was. “You’re American?” a teenage girl from Senegal asked me. “Who do you think is better—Rihanna or Beyoncé ? I told her Beyoncé. “Yeah,” she said, “me too, but the boys all like Rihanna.”

My husband, who is also American, and I came to France in 2010, when he was offered a job at a big Parisian research institute. We’ve now been here for three and a half years; our daughter was born here, and we’re considering staying indefinitely. I don’t think either of us anticipated spending our lives in a country other than America. But as I’ve outlined in this series, several aspects of life here in this big welfare state are both easier and cheaper than in the U.S. What we are saving in child care and health care alone makes it hard for us to justify a move back, at least while we have small children. Indeed, until this year when I started working again full-time, we literally could not have afforded to return to the U.S.

Are we immigrants or just expats? I’m not sure. The distinction seems to involve both permanence and necessity. You’re not truly an immigrant, in the eyes of many, unless you are moving for a better opportunity than you’d find in your home country. Expat carries with it the sense of choice, but also a whiff of flightiness and dilettantishness, the idea that you’ve rejected the country of your birth for reasons of lifestyle rather than need. For us—and for many others, I assume—it’s a bit of both. During the economic crisis, the number of Americans 25–34 living abroad went from 1 percent to 5.1 percent, and the number of Americans who said they were interested in living abroad jumped from 15 percent to 40 percent. Though the government doesn’t keep exact numbers, it’s estimated that more than 6 million Americans are living and working outside the U.S.

In the eyes of the French government, I’m an immigrant. As Congress continues to debate how to handle the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in America, it strikes me that although it’s never easy to immigrate, at least in France there’s more clarity and more humanity in the path to citizenship than there seems to be in the U.S. (Even if the required classes are a little boring and condescending.)

France has the second-largest immigrant population in the European Union, according to Eurostat. It has its share of undocumented immigrants, and the government has come under fire for its strict deportation policy toward the Roma, a stateless group migrating to France largely from the EU countries of Romania and Bulgaria. However, France’s deportation rate is nowhere near ours in the U.S. France deported 33,000 people in 2011; in the U.S., the number was closer to 400,000. Even adjusting for differences in population, the U.S. rate is double that of France.

In France, if you can pay for yourself and prove you’re not living off the state, you can pretty much assume you can stay. All three of the women who have cared for my child since she was born are immigrants to France from the Philippines; all three came here illegally but are now legal residents with work permits much like mine. One of them came to France 12 years ago under a false passport and worked illegally for 10 years. But at the end of that decade, she took documentation of her previous employment and statements from her employers to the prefecture, and the French government OK’d a work permit. She must renew it every year, and at each renewal she must prove that she is making enough money to pay her taxes and social charges. As long as she does this, she can stay in France.

Were you ever worried about being deported? I asked her. “No, no,” she said. She has several family members who came to the country in the same way, and they are now legal residents with the right to work.

Unlike the U.S., France doesn’t convey citizenship automatically at birth: My daughter was born in France but is American because my husband and I are both foreigners; she won’t be able to apply for French citizenship until she turns 13. So it’s not as easy a path to citizenship as it is for children born in the U.S., but on the other hand, the path for people brought here illegally as children isn’t nearly as hard as it is in America. If you can prove they’ve lived and attended school here for at least five years prior, they can become French citizens when they turn 18.

You also have to prove you can speak French. This is another point of contrast with American immigration policy: France has an official language and a requirement of intermediate-level language proficiency for any immigrant, and the government will subsidize up to 200 hours of French-language instruction for each applicant. You’ll also have to prove something more slippery—that you’ve “integrated” into French society, “especially by adhering to the essential principles and values of the Republic.” (“I made sure I joined a lot of French organizations,” one American friend told me about her application process.)

There’s a difference between providing a relatively straightforward path to citizenship and welcoming immigrants with open arms, and France certainly has its share of problems and tensions surrounding these issues. France is explicitly secular and explicitly assimilationist in its immigration policy, even though it’s also home to the largest Muslim population in continental Europe. As the French population grows more diverse, there’s been an accompanying rise in far-right, anti-immigrant political power. The notion of what it means to be “French” is necessarily changing as the population changes, and there are a lot of people who hate this and blame it on people who look or act “foreign,” even if they are in fact French citizens. Little of this kind of profiling touches me—I’m white, I look “European.” I’ve never been stopped in the street and asked to show my papers, as has happened to all of my Filipina nannies at one time or another.

When I am profiled, it’s usually as a citizen of another EU country; people are quick to assume I’m German, Dutch, or English, all countries close to France whose citizens can and do immigrate here freely, without the need for a carte de sejour, a jour civique, and all that comes with it. Many are surprised when I tell them I’m American. Invariably, the first thing French people say is: “But you speak French so well!” It seems we’re not really known for our language skills, my fellow Americans.

Underneath this, though, is a surprise that an American would choose to live in Europe, particularly France—it’s like a vote of confidence from an uneasy ally, proof that we may be past the years of war, Bush, and freedom fries. And despite our murky immigration system and patchy social safety net, America is still seen by many here as a land of opportunity, wealth, modernity, and glamour. At the end of my jour civique, which came with a government-funded French lunch at a local restaurant, I chatted with the same Senegalese teenager and a woman from Russia. “Where are you from in America?” they wanted to know. I told them I’d moved from New York, and their eyes lit up. “Ah, j’adore New York,” one said. “Someday, I would like to go there.”