When I sit down with Jake Dell, the 27-year-old heir to Katz’s Delicatessen, at a table toward the back of his family’s storied restaurant, he’s staring distractedly into his phone. His expression reads one part bewilderment, two parts resignation.

“Did you know there was a Beef magazine? Or a Cattle Network?” he asks. “I’m head first in cattle pricing—more than I’ve ever been.”

Katz’s is New York’s oldest surviving delicatessen. It is also, of course, the restaurant where Meg Ryan faked an orgasm in When Harry Met Sally (and has a sign inside to remind you). But far more importantly, it is the ur-deli, a place that, for a certain kind of American Jew, might trump the Western Wall in the hierarchy of Hebraic cultural heritage sites. While the current location, with its schmutzy wood paneling and walls covered with photos of celebrity diners, merely dates back to 1949, the restaurant has operated on the Lower East Side since 1888, serving up heaping, hand-sliced portions of its smoky, peppery, and unctuously fatty pastrami, along with house-cured corned beef, bocce-sized matzo balls, and other classics of the deli canon. To step inside its front door, under the pink neon signage and past the curtain of salamis hanging in its window, is to be enveloped by the thick, meaty aroma of history (as well as a throng of tourists, especially if you show up on a weekend).

But with a throwback menu comes a throwback business model, the downsides of which are especially apparent in these days of astronomical beef prices. That’s one reason why Dell—whose grandfather purchased Katz’s in 1988 and who in recent years has taken over most day-to-day oversight from his father and uncle—is fretting. If you want to fully appreciate why a place like Katz’s is special, you have to appreciate its odd economics, which pretty much ensure there will never be another deli quite like it.

Courtesy of Kimberly Jones

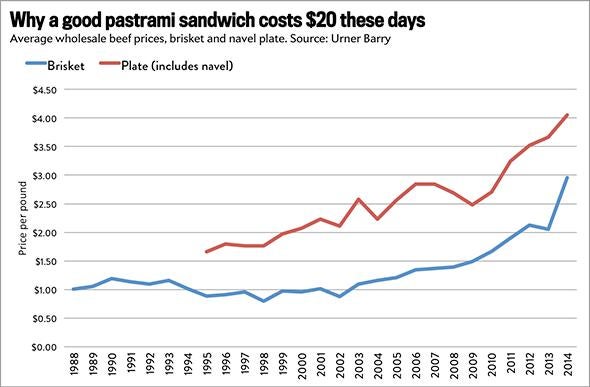

The fundamental problem facing every remaining deli, Katz’s included, is that the gargantuan sandwiches for which they are known aren’t very profitable. Rather, they’re a legacy of the early 20th century, when brisket (used in corned beef) and navel plate (the fattier, bovine belly meat Katz’s uses for pastrami) were considered cheap trash cuts and hundreds of Jewish restaurants could compete for immigrant clientele with rock-bottom prices. But the days of inexpensive navel and brisket are long gone—thanks in part to the national love affair with Texas-style barbecue—and delis can only raise their prices so high before turning off customers. As a result, the margins on a pastrami or corned beef on rye are perilously thin. In his 2009 book Save the Deli (an indispensible read for lovers of Jewish comfort food), David Sax writes that “most New York delis are breaking even or losing money on their namesake item.” Profitable sandwiches, he reports, make margins somewhere between 5 and 15 percent.

To put that in perspective, keep in mind that after subtracting food and labor costs, the median sit-down restaurant has a margin of roughly 35 percent (the exact number varies with average check size). “If all I did was sell sandwiches, I couldn’t pay the staff,” Dell tells me.

All of this might sound a bit suspect to someone who casually glances at Katz’s menu, which currently charges a hefty $19.75 for a pastrami on rye. But stop and consider it for a moment, and its easy to see how a nearly $20 sandwich might not actually be much of a moneymaker. Preparing a proper pastrami is a painstaking, labor-intensive process. At Katz’s, the raw navels are wet-cured for weeks before being coated in a dry rub of salt and spices, then smoked at a low temperature for about three days. Afterward, they’re steamed to soften up the meat, before the deli’s famous countermen—who are unionized, with health benefits—hand-slice it on the spot for customers. Cutting thinner slices with a machine would probably be more efficient and lead to less waste, but would leave the sandwich’s texture and character unrecognizably altered. In the end, it probably takes somewhere around a pound and a half of raw meat to yield a single, three-quarter-pound Katz’s sandwich.

“It’s a terrible Catch 22,” Dell says of the art of pastrami. “Because the thing that makes us loved is also the thing that makes it hardest from an economic standpoint.”

The economics have gotten markedly worse of late. Thanks to years of drought in Texas, the U.S. cattle herd is the smallest it’s been in more than 60 years, which has led to a sharp rise in beef prices and left Dell scouring Beef magazine for ideas about controlling costs.

Chart by Jordan Weissman

Despite all this, Katz’s remains a healthy, profitable business. But according to Dell, it makes most of its actual profits on side orders. Much as McDonald’s is really in the business of selling french fries and Coca-Cola for high markups—meanwhile using extremely cheap burgers to lure in customers—Katz’s keeps the lights on thanks to latkes, coleslaw, Matzo ball soup, potato salad, and Dr. Brown’s cream sodas. To pull this off, it needs a massive volume of business, bulked up by those droves of tourists (though, thankfully, it’s probably less of a tourist trap than its fellow survivor uptown, the Carnegie Deli). That foot traffic is possible in part because there simply isn’t much competition anymore. In other words, Katz’s lives on precisely because it’s among the last of its breed.

The newer generation of artisanal delicatessens that have risen up in recent years—restaurants like Brooklyn’s Mile End Deli and Washington, D.C.’s DGS Delicatessen—are fundamentally different. They serve their own excellent, obsessively sourced variations of house-cured and smoked pastrami (or Montreal-style “smoked meat,” in Mile End’s case). But volume isn’t really part of their equation. Instead, they emphasize profitable alcohol sales and have more varied menus with higher margin main dishes. And crucially, they can pack less meat onto the plate, which would be anathema at an old-school deli like Katz’s.

“Katz’s is super-special. It’s the only thing of its kind in the entire world,” Mile End’s founder, Noah Bernamoff, tells me.

The reason Katz’s was able to live on while its competitors disappeared largely boils down to real estate. As Sax writes in Save the Deli, New York’s delicatessens can basically be divided into two groups: those that rent their buildings and those that own. Famous renters, like the Stage Deli and 2nd Avenue Deli, have closed in the face of rent hikes. Famous owners, like Carnegie and Katz’s, have lived on. (And when 2nd Avenue Deli reopened, it bought a building … on New York’s 3rd Avenue). If Katz’s had to deal with a landlord, it would likely have disappeared or moved long ago.

Instead, it seems set to stay put indefinitely. Recently, news broke that Katz’s had sold the air rights over its iconic building. While Dell says he can’t share details of the agreement, including the buyer—it’s widely presumed to be a developer who bought adjacent lots on the block to build luxury condos—he does offer a list of things that won’t happen. Nothing is being built on top of Katz’s. Nobody is going to cantilever a building from next door. And Katz’s won’t be closing, even temporarily.

“We’re here, and that’s it, and we’re here to stay,” he says. But that doesn’t mean he can stop worrying about cattle prices. “My job is to freak out about the minor details that nobody will ever need to know, never see,” he says. “That’s what I do.”