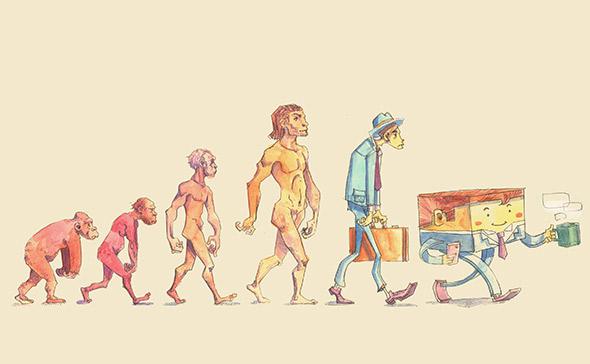

Early in Cubed, Nikil Saval’s detailed cultural history of how the office grew to become the definitive 20th century workplace, Saval presents a description of the stylish office worker, courtesy of Walt Whitman circa 1856.* At that time, nonmanual labor accounted for a minority of jobs in the country, and those who did spend their days in an office were often the source of derision. Whitman, for one, described office workers as “a slender and round-shouldered generation, of minute leg, chalky face, and hollow chest … trig and prim in great glow of shiny boots, clean shirts—sometimes, just now, of extraordinary patterns, as if overrun with bugs!—tight pantaloons, straps, which seem coming little into fashion again, startling cravats, and hair all soaked and ‘slickery’ with sickening oils.”

Adjust for some—but only some—changes in fashion and that passage could describe the put-together hipster or flashy banker you saw on the way to work today. You can take or leave the mockery (perhaps the description hits a little close to home), but Whitman’s words undoubtedly still resonate. Saval’s book accentuates the transformations that occurred as those weak and spindly office workers began to inherit the Earth, or at least the eight-hour workday. In 1880, less than 5 percent of the American workforce worked in nonmanual labor, although the number was much higher—in the 20-40 percent rage—in cities like Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Boston. As trade expanded across the country, the amount of clerical work increased. And as the number of people working in offices grew, the question arose of how to optimize efficiency and, in some cases, comfort in this new work climate.

To start, Saval explains, many offices took a cue from the factory and lined desks up in long rows. Then, in the early 20th century, two innovations emerged that would get recycled and reinterpreted in various ways over the next century. The first arrived courtesy of Frederick Taylor, a consultant and theorist who made it his goal to remove all inefficiencies from the office and argued for an extreme division of labor to replace what was the more fluid work style of the old clerks, who worked in small offices of four or five people and were responsible for a wide variety of tasks. Taylor created the position of the manager. As Saval writes:

By separating knowledge from the basic work process … the ideology of Taylorism all but ensured a workplace divided against itself, both in space and in practice, with a group of managers controlling how work was done and their workers merely performing that work.

Even as some offices today, particularly those in the tech industry, have attempted to move toward nonhierarchical models that recognize the benefit of idle, creative time, most still employ a version of this hierarchical, efficiency-driven system. The drive to get workers producing at highest capacity probably reached its apex with Robert Propst’s Action Office in the 1960s. The Action Office was an open-concept space consisting of several different working spaces, including a desk that you sat at and a larger drafting table that you could stand over. Propst’s second version of the Action Office, created after the first failed to gain traction in the marketplace, added walls of different heights around the workspace.

Propst’s ideas were received rapturously, heralded for finally allowing the office “to achieve the work utopia that it had always promised.” As Saval writes: “Most office designs were about keeping people in place; Action Office was about movement. For in keeping with the ergonomic thinking that Propst had been doing for years, the motion of the body assisted—corresponded to—the ceaselessly inventive motion of the white-collar mind.”

The results, however, were hardly radical. The Action Office, which was meant to liberate workers and get them moving around the office, instead led directly to the proliferation of its stifling cousin-in-design: the cubicle.

The same ironic story gets repeated with almost every grand design that Saval describes. Throughout Cubed, we read about “the dream of a better office,” but that phrase and others like it turn comical as we realize how little progress ever gets made toward turning that dream into reality.

That’s not to say that nothing has changed about office life at all in the past century. Saval emphasizes how offices were, for much of the 20th century, filled only with white men, an unfortunate reality that has slowly been reversed. But if the people doing the work have grown more diverse, any changes in how that work is actually done has tended toward the superficial, despite what the Taylors and Propsts of the world may have hoped.

In a New York magazine article last year, Matthew Shaer wrote about the new trend of bossless offices, where hiring and firing is done through consensus and teams complete projects with little to no hierarchical supervision. The notion appears revolutionary, but as Shaer writes, the results are anything but. Shaer describes watching a group of workers at Menlo, one of the companies trying out the “flattened office” theory, and realizing that “however ostensibly egalitarian this Menlo work team was, in practice, a leader had quickly emerged, and everyone else was falling in line.”

As Shaer points out after, that doesn’t take away from the project: “The triumph of the flattened office may be the creation of work environments in which leaders organically arise, and all employees feel a sense of ownership, whether real or imagined.” For the kind of worker who fits in at Menlo at least, the process is less oppressive, but ultimately a hierarchy ends up appearing regardless, and from an outsider’s perspective the work process is only slightly altered.

Photo by Katrina Ohstrom

Regardless of where it happens—in a cubicle, an open-concept warehouse floor, or a coffee shop—or how much personal freedom you have while doing it, office work has an underlying consistency. At its heart are basic and similar building blocks: assignments, projects, and deliverables spread out over, if you’re lucky, an eight-hour day. Even the shift to freelancing is not as tectonic on a day-to-day basis as it can appear from the outside. In fact, the first thing you learn as a freelancer is that the freedom it offers is mostly a fantasy. The experience is similar to the scene in When Harry Met Sally where Sally explains the false rationale behind deciding not to have kids with her boyfriend: “Joe and I used to talk about it, and we’d say we were so lucky … we can have sex on the kitchen floor and not worry about the kids walking in.” But of course, they never did. Freelancing in theory allows for impromptu midweek vacations and afternoon beers, but there’s still 40, 50, 60 hours of work to do a week, and it doesn’t get done by assuming you can now sleep in on Wednesday because you have no boss waiting for you at the office.

Of course, there are real changes facing people entering the workforce today and many signs that point to hard times coming for the white-collar worker: the decreased influence of private-sector unions, the push for students to choose vocational training over college, and the record number of freelance and temp workers—30 percent of the workforce as of 2006 and probably higher now. But the troubling aspect of these changes has little to do with management or design theories, with where and how people do their work, which is what most of Cubed focuses on. What’s worrisome about the future of work today is the seeming irreversible loss in stability, the increasingly prevalent notion that you can’t depend on a job for more than a few months.

Saval confronts this uncertain future at the end of the book. Recent changes, Saval argues, suggest that “the career path that defined the white-collar worker for generations … is coming to a close, and that a new sort of work, as yet unformed, is taking its place.” It’s a compelling conclusion, but one that the rest of Cubed hasn’t properly prepared us for. Saval begins the book by acknowledging in a footnote that it will ignore the “wider world of work,” which is precisely what we would need to know about to understand what comes next for the office worker, or to comprehend what the nature of work might look like if offices are in fact on the way out as the most common workplace.

However, if Cubed doesn’t serve well as a prophetic text, in its best moments it does offer some insight into what we might be losing. At one point, in one of many pop culture examples used throughout the book, Saval references Tom Rath, the middle-manager protagonist of the 1955 novel The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, who at the end of the book turns down “an executive position so that he could work less and spend time with his family (but still earn enough money to maintain a large home in suburban Connecticut).”

On the one hand, Rath represents a bygone era, where similar middle-management positions provided so many people with a cozy middle-class life. But Rath’s decision is also one that seems foreign to us for reasons beyond the state of the economy or the job market. Many middle-class Americans fail absolutely at creating the kind of boundary between work and life that Rath does in the moment he rejects his promotion. That our lives are defined by work is a common notion in our culture, instilled in us when we’re asked what we want to be when we grow up as kids, confirmed by quizzes in high school social studies that tell us what career we’re most suited for, and set in place by the stresses of choosing a major in university.

The men and women who dominate Saval’s story are similarly work-obsessed. They are theorists, innovators, and consultants who tackle the problem of the unsatisfied employee in one way: by attempting to make work as comfortable to live in as possible. Yet most of us have probably worked jobs that would never be satisfying, regardless of what perks came with them. As a university student, I spent one summer working at a supermarket. Most of my memories from that job are of interminable shifts and downcast co-workers, with the exception of one department manager—one Tom Rath, you might say—who had spent years at the company but had an upbeat energy distinctly different from anyone else with the same level of seniority. The reason for that became clear when I talked to him about Don DeLillo, about journalism, about things that had nothing to do with putting merchandise on the shelves. Evidently, all these activities outside of work were what actually mattered to him.

If the job market is set to remain as unpredictable and insecure as we’re watching it become, then putting all our emotional stock in our work life will become increasingly unsatisfying. Of course, none of this is meant to dismiss the grave issue of unemployment and underemployment that’s affecting so many today. But reading Cubed, and seeing people from 20, 50, and 100 years ago suffering the same workplace woes that we face today, should make us consider trying to change the story we tell: to remove work as the paragon of our day-to-day life. The fact of the matter is much like Lester Freamon put it in The Wire: “The job will not save you.” To which I might add: Certainly not in this economy.

Correction, April 10, 2014: This article incorrectly stated the date of a Walt Whitman description of office workers. It was written circa 1856, not 1936.

—

Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace by Nikil Saval. Doubleday.

See all the pieces in this month’s Slate Book Review.

Sign up for the Slate Book Review monthly newsletter.