The global pool of wealth is bigger than ever. Credit Suisse’s 2013 Global Wealth Report puts it at $241 trillion, or 68 percent bigger than a decade ago. That’s not to say that it is being spread more evenly—10 percent of the world’s population possesses 86 percent of the money. Wealth is being created and stockpiled so fast, the report projects, that in just two generations’ time, there could be 1 billion millionaires in the world. That means roughly 1 in 5 adults could soon call themselves a millionaire.

Even billionaires aren’t the exotic species they once were. According to Forbes, there are 1,426 of them today, with more than 200 of them having reached 10-figure status in the last year alone. When Forbes started its billionaire list 25 years ago, there were only 140. It’s hard to imagine the likes of Evan Spiegel, 23-year-old co-founder of Snapchat, turning down multibillion-dollar offers from Google and Facebook even a couple of years ago. Hitting the 10-figure mark: not as cool as it used to be.

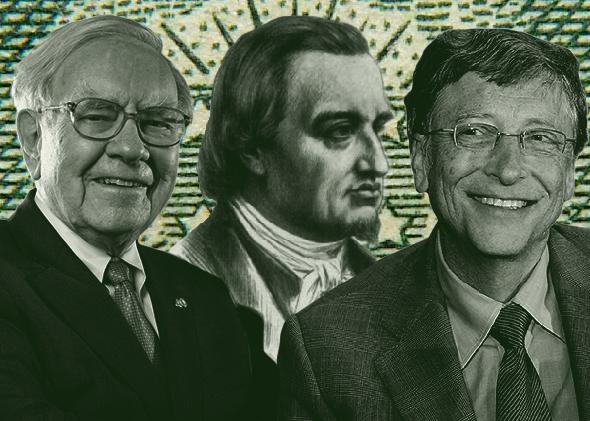

It wasn’t always so easy. When John D. Rockefeller rose from a clerk earning 50 cents a day at a produce company to become the world’s first billionaire a century ago, the fortune he amassed would have made Bill Gates swoon. In 1918, Rockefeller’s taxable income was a staggering $33 million, or slightly more than $550 million in today’s dollars. That dwarfs Warren Buffett’s 2010 tax bill, where he paid just under $7 million on $40 million in taxable income. At the time, Rockefeller’s fortune alone amounted to 1.53 percent of the U.S. economy, the equivalent of some $350 billion today.

But even then, Rockefeller wasn’t halfway to the next monetary milestone: a trillion dollars. No one since has even come close. Here’s a clue to just how alien a concept of personal wealth this is: So far, neither Merriam-Webster dictionary nor Oxford have acknowledged the word trillionaire. How does one become something that doesn’t exist yet?

Rockefeller’s rise to extreme wealth came from a familiar source: oil. In 1870, he founded the Standard Oil Company; by the end of that decade, Standard Oil was refining 90 percent of the oil in the U.S. The timing of Rockefeller’s ascendency was perfect: The post-war U.S. was expanding westward and petroleum became the global currency of industrialization. Rockefeller’s road to 10 figures wasn’t paved with good business sense alone; he also benefited from monopolistic practices. When the Supreme Court ordered the breakup of Standard Oil in 1911, the company spun off oil predecessors into the titans of the modern industry: Conoco, Amoco, Chevron, Exxon, and Mobil.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the Rothschild family had built the infrastructure of modern banking. The patriarch, Mayer Amschel Rothschild, set the family on a path pioneering modern finance, acting as a central bank to the continent, striking deals that helped finance the infrastructure of European industrialization, and making them the wealthiest family the world had ever seen.

Could the rise of Rockefeller and the Rothschilds be replicated to create a trillionaire? First, you have to actually want to make that much money. Rockefeller was driven by what he thought was a higher calling to make more and more, but also to give it away. “I believe the power to make money is a gift of God,” Rockefeller said. “It is my duty to make money and even more money and to use the money I make for the good of my fellow men.”

With his unimaginable wealth, Rockefeller pioneered a contradictory pursuit: the art of giving it away. By the end of his life, he had given away more than $500 million of his fortune, giving rise to modern philanthropy. He invested heavily in education; from his wealth, the University of Chicago was born. He poured funds into medical research to cure diseases and medical schools to train doctors.

Rockefeller strove for “efficiency in giving” just as in his business pursuits, in order “to solve the problem of giving money away without making paupers of those who receive it.” It’s an instinct that two of today’s wealthiest—Bill Gates and Warren Buffett—share. The pair’s donations to Gates’ foundation made it a $40 billion juggernaut. And they don’t just want to give their own cash away; they want their fellow billionaires to pledge to give the majority of their wealth to philanthropy. That makes Gates, Buffett, and the many who wish to emulate them all longshots for trillionaire status.

Following in Rockefeller’s footsteps in the extraction business isn’t a sure bet, either. There surely are still billions to be had in oil, but trillions? In an already competitive industry, production has gotten more complicated and expensive. Rockefeller built Standard Oil in the early days of the commercial oil business and relentlessly absorbed competitors to create a monopoly. So tight was his grip on the market that it spurred the antitrust movement, which hinders his successors from achieving the same sort of dominance. As Rockefeller’s oil prepotency waned, global production flourished; in a frantically developing industrialized world, oil reserves took on strategic importance. That meant the countries resting atop oil reserves weren’t going to let it go. Governments have become accustomed to demanding a larger share of the profits for themselves.

Could a new wonder mineral arise to anoint a new Rockefeller? It’s certainly possible. With the explosion of mobile technology from cellphones to laptops to hybrid cars, the insatiable need for batteries has made rare Earth metals a hot commodity. But they, too, are found within national boundaries. In fact, 97 percent of the world’s rare Earth metals are found in China, giving the country a virtual Rockefeller-like monopoly that it won’t let slip away.

A century ago, the world’s wealthiest rode a wave of industrialization in the U.S. that ushered in a Gilded Age. The explosion of communication technology and transportation transformed the American economy into a truly national marketplace. It was a period that created the American middle class, as well as setting the stage for American industrialists to accumulate vast fortunes. Today, a similar process is occurring on a global scale. Global communication and transportation lines have now stretched beyond borders and fuelled the growth of a global middle class. Programmers in India are now part of the labor pool for American companies, which in turn makes them new consumers. That’s not to say that the distribution of wealth has gotten more equal, but more wealth than ever in more parts of the world could set the stage for a trillionaire to emerge.

The two industries are best positioned to take a billionaire to the next level are technology and retail, for the same reason: Both use a global labor pool to make affordable products, inexpensive enough that workers can soon become the consumers of the products they are making. Of course, the tech industry is building on Internet infrastructure to create billionaires faster than ever. In October 2010, photo-sharing social network Instagram came into being; less than two years and a mere 13 employees later, Facebook snapped up the company for a cool billion. A look at the Forbes list of the world’s wealthiest shows that the rise of technology and telecommunications has made a big impact: Mexico’s Carlos Slim, who vies with Gates for the top spot on global-richest lists, made the bulk of his fortune in telecom.

Lurking just below these technology magnates are Amancio Ortega, the founder of Zara; the Walton family and their ubiquitous Walmart chain; the Mars family of candy fame; Stefan Persson, chairman of H&M; and Jeff Bezos of Amazon. The rise of these individuals and families is perhaps more surprising than that of Gates, Slim, and their peers—and may be revealing about the clearest sustainable path to 10 figures. These magnates are best positioned, in different ways, to find and use available labor no matter where it is. That will help them sell their products at prices that a wealthier world will be able to afford most quickly. For that to happen, they’ll need emerging markets to continue emerging, creating not only employees but customers, too. If that happens, in two generations—about 60 years—Credit Suisse predicts there could be as many as 11 trillionaires walking among us.