This month, Slate is exploring how to reinvent American manufacturing. We’d like to hear your best ideas for that! Please submit them here.

Steve Jobs once told my graduating class to “stay foolish.” I’ve rarely met anyone who embodies that advice as much as Bre Pettis, founder of the Brooklyn-based home 3-D printing startup MakerBot. If anything, Pettis embodies it more than Jobs himself, who wasn’t too foolish to build Apple into the most profitable company in the world. It’s unlikely Pettis will ever do the same, but there’s still something Jobs-like about this ebullient former middle-school art teacher, puppeteer, and assistant at Jim Henson’s Creature Shop in London. Pettis has now moved on to run the most influential company in the “3-D printing revolution“—whatever that might turn out to be.

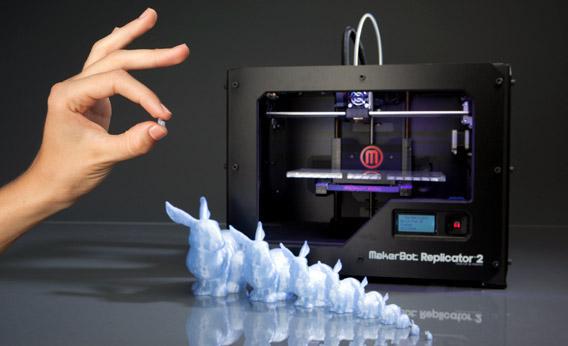

This week Pettis did two things that would make Jobs proud. He introduced a sleek new $2,200 desktop device, the MakerBot Replicator 2, which is the closest thing yet to a 3-D printer for the masses (though it’s not that close, as I’ll explain). And he opened MakerBot’s first retail store, in Manhattan’s trendy NoHo district.

Like the Apple store, the MakerBot outlet is designed to showcase the company’s products in a playful, interactive environment. Unlike the Apple store, practically nothing on the shelves serves any legitimate purpose—except, just maybe, the 3-D printers themselves.

“What’s the most useful, pragmatic thing here?” I asked Pettis at the grand opening on Wednesday. “Probably this watch,” he said, beaming as he bounded over to a partially 3-D printed display case. He pointed to a red-and-black plastic watch that looked like something I might really have coveted in fourth grade, before you could just check your iPhone to tell the time. Still, I had to admit that a watch seemed like an enormously impressive thing to construct out of a home 3-D printer.

“So, the timing mechanism …” I began. “That’s the one component we put in there,” he explained brightly. “Everything else is 3-D printed.” In other words, MakerBot’s new Replicator 2 assembled the whole watch from scratch, except for the part that makes it a watch. The next display case housed a retro-looking 3-D-printed cassette tape, which turned out to be a 3-D-printed cassette-tape shell with a non-3-D-printed MP3 player hidden inside. The MakerBot Mixtape sells for $39. Or, if you’re a proud Replicator 2 owner, you can order a kit online for $25 and print out the shell on your home machine.

To point out that these crafts are frivolous is not to diminish what the company has achieved in the three years since Pettis co-founded MakerBot with Adam Mayer and Zach Smith. Building on open-source technology from the RepRap project, MakerBot has established itself as the leader in the infant field of home 3-D printing. (Industrial 3-D printing, or additive manufacturing, is a different ballgame.) Its latest devices, the sleek Replicator 2 and Replicator 2X, represent a startling evolution from its charmingly ramshackle early efforts, the Cupcake and the Thing-o-Matic. Those wood-framed gadgets required significant assembly, operated slowly and crudely, and amounted to expensive toys for avid hobbyists. The new ones come fully assembled, with a compact shape and powder-coated steel frame. And they’re swift and precise enough to merit a place on the desks of professional engineers and architects, who can use them to quickly fabricate intricately detailed scale models of their computer-generated designs. Reviewers are calling the new Replicator the finest desktop 3-D printer ever.

At this point, though, that isn’t saying much, at least as far as the average consumer is concerned. As inspiring as the possibilities are for a machine that can translate virtually any design into a real object before your eyes, the limitations remain deflating. You can’t build anything larger than a shoebox. You can’t build out of any other material than polylactic acid, a biodegradable plastic derived from corn starch (though the PLA at least now comes in a wide array of colors). You can custom-make just about anything you want, provided you’re skilled in computer-aided design. But you’d be hard-pressed to find anything on the Thingiverse—the online community where users share their virtual blueprints—that you’d ever really need.

MakerBot’s retail store, studded with novelty items that a cynic might be tempted to label “junk,” is a testament to that. The highlights are an enormous marble run that occupies the store’s main display window, and a row of “gumball machines” that vend a variety of 3-D printed figurines. The machines accept tokens that cost $5. The toys that pop out are of comparable quality to the ones that cost $1 in the little machines that line the entrance to your local grocery store. It’s basically the 21st-century version of a pottery boutique.

And yet the sheer joy and can-do spirit inherent in what Pettis and his company are attempting are exactly what Jobs was urging us newly minted college graduates to cultivate. Pettis’ father Chuck, who now works for his son in marketing, told me that Bre has always been this way. As a kid he was obsessed with bicycles—“he would take ‘em apart and kluge ’em together,” Chuck recalls. As an adult he has bought dozens of beat-up old cars just to tinker with them. He went to school at Evergreen State in Olympia, Wash.—“the college for people who want to educate themselves,” in his father’s words—and later taught at a Seattle middle school. Bre still has the enthusiastically geeky air of a great shop teacher. In his pre-MakerBot days, an employer described him to the Wall Street Journal as “Mr. Rogers, Mr. Wizard, and Bill Nye the Science Guy rolled into one.”

On Wednesday, Bre Pettis looked like the happiest kid on earth as he walked into his retail store to see it open and running for the first time. “This is so good,” he raved to an employee, clapping him on the shoulder. “Nice! Dude!” Watching a young boy operate the big plastic marble run, he urged him on like Dean Moriarty exhorting a bop musician in On the Road. “Turn the wheel! Turn the wheel! Wow!”

Courtesy Makerbot/Bre Pettis.

In an adulatory new feature story on MakerBot, Wired editor-in-chief Chris Anderson (a serious and accomplished DIY-er himself) throws around words like “mainstream,” “masses,” and “new industrial revolution.” The Replicator 2 represents “MakerBot’s Macintosh moment,” he writes. “Just as nearly 30 years ago Apple made desktop publishing mainstream, the aim with the Replicator 2 is to take something new to the masses: desktop manufacturing.”

I’m not buying it—and unless you’re already into maker culture and have money to burn, I bet you aren’t either. Anderson is more convincing when he compares the 3-D printing movement to Jobs’ pre-Apple venture, the Homebrew Computer Club. It took nine years from the time of that seminal group’s founding in 1975 to the launch of the Macintosh in 1984. (Apple itself was incorporated in 1977.) On that schedule, MakerBot still has another four to six years to build its Macintosh—a device useful and affordable enough to appeal to regular consumers. A more realistic reference point for the Replicator 2 might be the first Apple II—a piece of hardware that’s a gigantic leap forward but is still rather primitive in its capabilities.

Whether 3-D printers will ever be as popular as desktop computers is an open question. At this point, MakerBot’s Replicator 2 should be celebrated for what it is—a fascinating and delightful innovation in a still-nascent technological realm—rather than for what it is not, which is a revolutionary, primetime-ready consumer device.

Pettis himself says the true potential of home 3-D printing remains to be discovered, whether by MakerBot or by MakerBot users. (The company has taken heat for making the Replicator 2 closed source after keeping previous versions open source—a concession, Pettis says, to the realities of the business world. As of Thursday, it’s discovering that backlash is also a reality of the business world: Users have launched an “Occupy Thingiverse” protest on MakerBot’s online design marketplace.)

Pettis happily admits that most of what’s in the MakerBot store so far is more amusing than revolutionary. But he says he’s always believed that what’s amusing today could turn out to be revolutionary tomorrow. “I think that true innovation is often found on the edge of what’s absurd,” he says. He may not be the next Steve Jobs, but Steve Jobs would surely approve.

This month, Slate is exploring how to reinvent American manufacturing. We’d like to hear your best ideas for that! Please submit them here.