We’re living in the age of the schlockumentary. Ideally, a documentary should have an arm’s-length distance between subject and chronicler. And one hopes that the director is there in service of the viewer, not the subject. In the arts world, that ideal is getting harder and harder to find. A vast cottage industry has sprung up around the making-of documentaries for movies and even CDs. They sport a professional patina and are often enjoyable to watch. But they aren’t real documentaries: There’s never anything in them that any of the interested parties (stars, director, the producers, the studio) don’t want in them—and in the end, they’re being used to sell product.

It’s worse when you get into the real world. Consider Pearl Jam Twenty, the new documentary on Pearl Jam, by director Cameron Crowe. Back in the 1990s, Crowe, a friend of the band’s, wrote the Rolling Stone cover story on the group, one of the only substantive interviews Vedder and Co. gave during their early stardom. Here we are almost two decades later, and Pearl Jam has the same friend do a “documentary” on them. Pearl Jam Twenty is a fun movie with lots of great early footage, but Pearl Jam’s corporation is listed as a producer, so you know there’s not going to be anything in it that doesn’t jibe with the band’s image of itself.

Our leading schlockumentarian is Martin Scorsese. Now, Scorsese is known for his piercing use of rock in his films; beyond that, he was one of the editors for Woodstock and directed The Last Waltz, which is still the gold standard for rock docs. But even in The Last Waltz you can see him work hard to burnish his buddy Robbie Robertson’s image. (Other members of the Band have said, for example, that Robertson’s theatrical backup singing was delivered to a dead mic.) No Direction Home, Scorsese’s celebrated four-hour documentary on Bob Dylan, was engrossing, but it was also based on interviews that the Dylan camp had already made and gave the director to build a film around. The film unaccountably received a Peabody for a practice that would be unacceptable in most journalistic outlets. When films or film screener discs are given out to journalists, the industry often includes things called electronic press kits, or EPKs, which feature pre-filmed canned interviews with the stars. No Direction Home is basically a high-end EPK.

Then Scorsese made Shine a Light, a filmed concert movie about a pair of Rolling Stones shows at the Beacon Theater in New York City in 2006. The beginning of the film sees Scorsese seemingly in a frenzy about getting the setlist for the show, which is delivered to him at the last second. Scorsese knew that the Stones had started most of their last 60 or 70 concerts with “Start Me Up,” and that men the Stones’ age rarely do anything radically new. Scorsese later admitted he’d had the setlist hours before the show, but that didn’t stop him from ginning up a fake drama that allowed him to insert himself into the film.

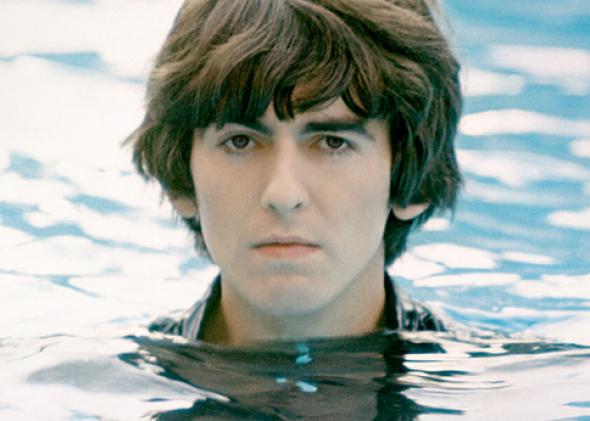

And now we have Scorsese’s George Harrison: Living in the Material World on HBO, an exhausting but not exhaustive look at the life of the Quiet Beatle. It is a signal work in the age of the schlockumentary. The film, all three-and-a-half-hours-plus of it, is, as you’d expect from Scorsese, a handsome presentation. It’s stately, respectful, at times touching, and bears the marks of his typically exhaustive research. But in the end, the documentary contains nothing that the subject, were he still alive, would have found objectionable.

***

There are two ways to look at George Harrison. The nicer one is that he was a top-line and underappreciated guitarist, good enough to have spent many years as a close friend and occasional collaborator of Eric Clapton’s; that he wrote at least two classic songs (“Something,” and “Here Comes the Sun,” two more than most songwriters write) and another half-dozen quite good ones; that he was one of the original rock humanitarians; and that, all in all, given a career he could never have dreamed of, he made his way through it with a great deal of dignity. Like John Lennon, he suffered a grievous assault for no other reason but that he was famous (a knife attack on the eve of the millennium, which nearly killed him); and he died too young, of lung cancer, in 2001, not yet 60.

The other and arguably more realistic appraisal might be that George Harrison’s contributions as a guitarist were pretty much limited to a few Beatles riffs and the fine and quite recognizable slide sound he developed in his solo years. That producing two great songs after 10 intimate years with two of the top songwriters of the 20th century isn’t awfully surprising, and that even if you throw in the other half-dozen, the total isn’t much for a recording career that spanned almost 40 years; that most of his Beatles songs are inferior; that his voice was weak; that he was more than a bit of a mope; that he thoroughly embarrassed himself on his only American tour; and that the greater share of his solo work was poor, and that some of it was dreadful.

You can imagine which side of this Scorsese takes. For Beatles fans, there’s a lot to see in the documentary. The first half, which airs Wednesday evening and takes us up to “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” begins with a tour-de-force of a collage, set to Harrison’s “All Things Must Pass,” that captures some of the feelings of loss his death left among his friends and then efficiently limns the postwar era of Harrison’s (and the other band members’) childhood. (He didn’t grow up with indoor plumbing.) There’s also a great deal of priceless footage of the group’s early years, even more than in the still enjoyable Anthology series of Beatles documentaries. (Among other things, Scorsese handles the switch from the kids’ black-and-white world to a color one with some lancing cuts and song cues.) Scorsese was also given access to some of Harrison’s letters to his parents, which are read by Harrison’s son Dhani.

Scorsese gets Klaus Voorman and Astrid Kirchherr on-screen—they were the Beatles’ closest friends during their time playing in the red-light district of Hamburg. There are memorable and haunting images of the doomed Stu Sutcliffe, the group’s original bassist and Kirchherr’s boyfriend. Living in the Material World doesn’t have any voice-over narration, so there’s a recurring floating feeling as you watch. Here, we hear about the Beatles’ reaction to Sutcliffe’s death but not about how or why he died. (It was a brain aneurysm at the age of 21, possibly stemming from a street fight the group had gotten into.)

The second half, which is being shown Thursday night, deals with the breakup of the Beatles, similarly indistinctly; Harrison’s increasing interest in Indian music, religiosity, and mysticism; events like the Concert for Bangladesh (still a sublime concert experience on DVD, incidentally); and, superficially, his solo career and activities in the last 30 years of his life. (Among other things, he stepped in to bail out the production of Monty Python’s Life of Brian, and hung out with race-car drivers, like England’s Jackie Stewart.)

Now, Harrison’s a not-uninteresting figure and probably warrants a documentary. And again, Scorsese’s army of researchers has rounded up some incredible footage, like the extended takes of a British TV show in which questioners try to get to the core of Harrison’s religious beliefs.

But Living in the Material World fails on several levels.

For the first, it’s not really fair, I suppose, but Harrison’s natural diffidence doesn’t work for him in this context. Particularly in the first 45 minutes, dramatic events like formation of the Beatles and the death of Sutcliffe tend to overshadow the film’s ostensible subject. It doesn’t help that Scorsese keeps getting distracted by one of Harrison’s bandmates in particular. (I can imagine someone who knew nothing of the Beatles watching the first part and saying, “I don’t really get that George guy, but who was that John character? Someone should make a four-hour documentary about him.“)

Second, the EPK origins of the thing are always on display. Consider Harrison’s 1974 solo tour. Scorsese slides in the news that the shows got some bad reviews, but only, in trademarked schlockumentary fashion, in the context of someone leaping to Harrison’s defense. In fact, the tour was a legendary debacle. For the shows, Harrison foisted on the audience not one but two sets of Ravi Shankar, harangued fans with his beliefs, and insisted on changing song lyrics to remind people of how religious he was. (He even did this with Beatles songs he didn’t write. He sang Lennon’s “In My Life” as “In my life/ I’ve loved god more.” For some reason, such interpolations weren’t popular.)

The show was so bad that the Rolling Stone feature on the fiasco (“Lumbering in the Material World”) featured this analysis of the show in its fourth paragraph: “I hated it. … One, it’s too long. Two, Ravi’s got to be one set. And three, George has to shut up.” That was from Harrison’s publicist. The footage from the tour Scorsese shows here, which I’d never seen before, shows that Harrison’s crimes were not just artistic but sartorial. He looks like Mork from Ork’s twit British cousin.

Harrison, after some soundtrack work, released nearly a dozen solo albums after the breakup of the Beatles. Scorsese’s interest in them stops at the second, All Things Must Pass. (Another of the documentary’s coup interview subjects: ATMP producer Phil Spector, who it turns out sounds like Peter Falk. Unmentioned here is the fact that Harrison once recalled that it took Spector about 13 cherry brandies before he could get to work on the album.)

Besides “Isn’t It a Pity,” the title track is probably my favorite Harrison song; it has a great Spector production and features Harrison’s most resonant vocals. But it’s also true that the mystical grandeur of the song’s title disappears when you pay attention to the lyrics: It’s really a fairly cold “sorry I had to break up with you” song, and has a lot of typically careless writing in it, too.

In other words, once Harrison’s way with a melody left him, early on in his solo career, he wasn’t left with much. If you wield your remote fast enough you can do a freeze-frame on a fleeting glimpse of a Rolling Stone review of Harrison’s Dark Horse solo album. (The headline is “Transcendental Mediocrity.”) This is the only sign of the almost unrelieved decline in Harrison’s songwriting and record-making talents after All Things Must Pass.

Maybe I’m being churlish, but I think a 200-plus-minute documentary about a songwriter should include something about the work he did in the last five-eighths of his adult life. Even the better songs from this period—“Crackerbox Palace,” say, or “Faster”—suffer from an uneven production and Harrison’s even more uneven voice. Am I the only person who thinks the charming “Crackerbox Palace” is decisively marred by Harrison’s effete delivery of the “We’ve been expecting you-oo-oo” line? Also unmentioned here is the fact that the only things resembling hits in the last 25 years of Harrison’s life were novelty numbers (a Beatles tribute song, “When We Was Fab,” and a cover, “Got My Mind Set on You”). Harrison wasn’t exactly David Crosby as a symbol of post-’60s rock-star artistic decline, but he was close.

And if you want to learn about Harrison the musician, that’s not here either. Whether as an oversight or because he simply couldn’t find anyone to make the case, Scorsese gives Harrison’s supposedly innovative guitar work about 12 seconds of testimony from Clapton. Another oddness: Scorsese lets Harrison, in a voice-over, give himself credit for being so daring as to write a religious song like “My Sweet Lord.” (It’s a great single, but in fact, a lot of rockers at the time had done such a thing—Clapton and “Presence of the Lord,” the Byrds and “Jesus Is Just Alright,” etc.) But he doesn’t detail the famous suit over the song, in which Harrison was ultimately found to have unconsciously plagiarized the 1963 girl-group classic “He’s So Fine” to write it.

Here as elsewhere in the film, Scorsese makes elliptical reference to things but doesn’t give viewers the full story. We get Billy Preston giving a short account of how the song was written, while he and Harrison were on tour with Delaney and Bonnie. (This was an American hippie singing ensemble of the era. Clapton and Harrison unaccountably found them irresistible.) The Preston comments seem to be a nod to the real story of the genesis of the song, which doesn’t reflect well on Harrison. According to an account given by Delaney Bramlett to later Harrison biographers, he had deliberately made up for Harrison a sort of nonce song to illustrate how you could take a well-known tune, like “He’s So Fine,” and turn it into a religious song by adding lyrics about god. That interaction is the genesis of Harrison’s “My Sweet Lord.” In other words, Harrison had not only known the song was plagiarized, he’d stolen the plagiarized idea from Bramlett.

I take the point that it’s hard, when it comes to profiling rock and movie stars, to get into their personal lives, which in the vast majority of cases are uncomfortable things for their spouses to talk about. (That’s a nice way of saying that most stars, married or not, aren’t monogamous.) To Scorsese’s credit, and to her credit as well, he gets Olivia Harrison, who was with George from the mid-1970s to his death in 2001, to address Harrison’s attractiveness to women and the resulting “challenges in the marriage.” “Sometimes,” she reflects, “people say, ‘Well, what’s the secret of a long marriage?’ You don’t get divorced!” And we get passing mention of the famous love triangle involving Harrison; his first wife, the model Pattie Boyd; and Clapton, which played itself out against the writing of Clapton’s “Layla” and “Bell Bottom Blues” and resulted in Boyd’s leaving Harrison.

There’s a lot more to the story. In her memoir, Wonderful Tonight, Boyd says Harrison was highly controlling as a husband, pursued other women, lost interest in her, and then spent all his time puttering around his estate and filling it with Hare Krishna families. (The best part of the story, also not told in Living in the Material World, is how Clapton started going out with Boyd’s 17-year-old sister Paula to get close to Boyd. A juicy footnote: Clapton relates in his own, oddly affectless autobiography about how, one gay evening at Harrison’s house, Harrison took him aside and suggested he, Clapton, seduce Boyd so that Harrison could make a run at sister Paula. Ah, the ‘70s.)

***

Finally, the film really never investigates the real mystery of Harrison: What was he so morose about? Now, Ringo Starr is one who appreciates the cosmic joke life played on him. He has a cheerful acceptance of life’s whimsy, hiding what no doubt has been his daily prayers since circa 1963: “Please, God, I don’t know what a goofball like me did to deserve this life, but thank you very much, and please let me know if I’m doing anything that would cause you to end it.” Harrison, by contrast, has always had a sense of the aggrieved about him. I just don’t know what the source of it was. In Harrison’s mini-autobiography at the front of I Me Mine, the unasked-for collection of his song lyrics, he seems mostly unhappy about … the travel indignities he suffered during the Beatles years. In the documentary, Scorsese plays the price-of-fame card heavily. “It’s fun,” Starr says, “early on. But then you want it to stop, and it never does.”

Whatever the source, Harrison seems to have been on a quest to find some answers or relieve some pain. We see a bit of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the cartoony imp who founded the transcendental meditation movement and with whom the Beatles, led by Harrison, and some other pop icons of the day became infatuated in 1967. Here as elsewhere, we don’t hear about the deflating punch line: How Harrison and Lennon, his biggest devotees, left his ashram in a storm after rumors (never really substantiated) came out that the Maharishi had been making passes at Mia Farrow.

Scorsese just doesn’t seem interested in addressing the source of the impulse that moved Harrison into religious mysticism. (In some of the letters to his parents we hear in the film, Harrison’s growing interests in this area sound like something out of Tommy. That’s not good. Harrison’s drug use, which he might have been using as self-medication, is also given sidelong mention, but the severity of it is never explored.) But that something pained Harrison it is taken for granted here. One nut in full Krishna regalia says that chanting “helped George overcome feelings of distress and anger.” What feelings of distress and anger? Rock stars have emotional pain too, of course; I’m not disputing that. But everyone seems to accept that Harrison had some problems, but we never hear what they were.

The end of the documentary is the most memorable, as the lovely Olivia Harrison, who comes across as both gracious and down to earth, is allowed to speak at length about various aspects of their lives. It can’t have been easy being married to a rock star. She gives a harrowing, mordantly funny account of the knife attack, and some moving words about Harrison’s death, from lung cancer, in a hotel in Switzerland in 2001.

The sad thing about Living in the Material World is that Scorsese has so bowdlerized Harrison’s life that he comes off as somewhat boring. One bit of testimony from Harrison himself inadvertently captures how the film makes him seem almost evanescent. He says he sometimes reflects on death and wonders what he would miss in life. He acknowledges his son who, he notes seriously, needs a father. “Other than that,” he says, “I can’t think of much of a reason to be here.”

It’s a deflating line, and one I think that he doesn’t deserve to leave as an epitaph. I like more songs than Harrison’s six or seven good ones; The Concert for Bangladesh film alone is a great legacy, and I celebrate his quirks, like his lifelong, fruitless battle against Britain’s high tax rates. (In I Me Mine he reproduces a 1-million-pound check he’d sent to the U.K. tax authorities. That was a mind-blowing amount of money in 1973.) Just in Beatles lore alone, he’s something of a relief, particularly when set against Paul McCartney’s fatuousness, Lennon’s malevolence, and Starr’s chirpiness. Perhaps the odd behavior his first wife observed had something to do with depression over the declining critical and commercial appeal of his work. These are all elements that would have broadened our understanding of Harrison the man. By removing the edges that gave the man’s life some bite, Martin Scorsese hasn’t done George Harrison’s legacy any favors.