You Must Remember This is the podcast that tells the secret and forgotten history of 20th-century Hollywood. Creator and host Karina Longworth shares some of the research that went into the episodes in an excerpt here on Slate. Listen to the complete Episode 91 on Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, and What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? below, and subscribe to You Must Remember This on iTunes.

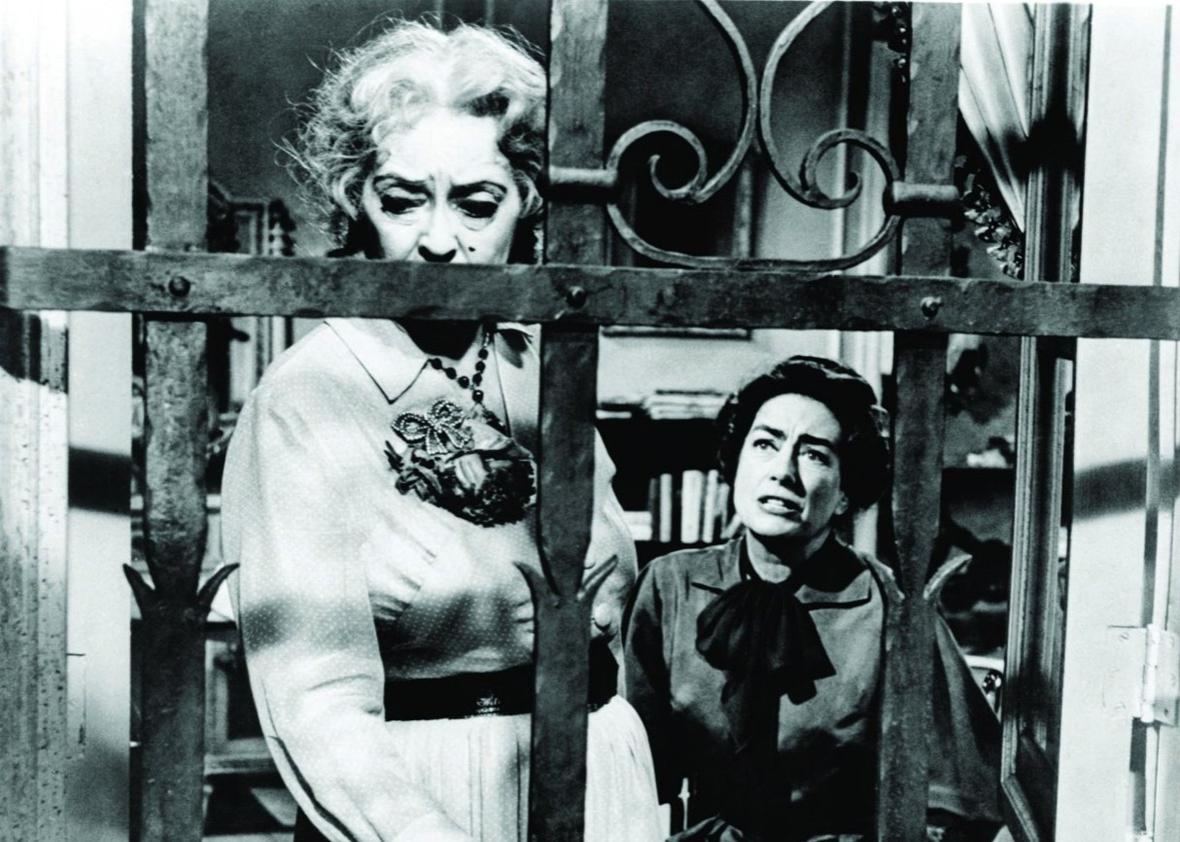

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is the lynchpin of the final chapter of Joan Crawford’s film career, and almost 40 years after Crawford’s death, it’s the film that has become probably Crawford’s most iconic to younger generations who weren’t around to witness her stardom in real time. It’s a movie that’s become all the more notorious because of the meta-quality attributed to its story and casting. A thriller about two former stars with a historically antagonistic relationship to each other, whose forced cohabitation leads to mortal combat, Baby Jane was savvily marketed so that audiences believed, rightly or wrongly, that they were seeing some version of reality playing out on screen. Nowadays, it’s basically taken as a given that Crawford and Bette Davis not only hated each other, but would have actually been happy to have been given license to kill each other. But how real was the feud between Davis and Crawford off-screen?

Crawford and Davis lived parallel lives with many similarities and some significant differences. Both had their brightest and most uncomplicated years of stardom in the mid-1930s. Both took four husbands and adopted children who they later disowned. And both actresses became known for playing what historian Jeanine Basinger called “exaggerated women,” stars who specialized in playing women who were larger than life in a literal sense, in that their characters’ lives could not accommodate the size or intensity of their ambitions, emotions, neuroses, or desires. This was perfect for films of the 1930s, but as time marched on and Davis and Crawford both gradually got older, and audiences began going into their movies with a calcified idea of what a Crawford or Davis performance would give them, their very presence could only overwhelm whatever dramatic situation the film tried to put them into.

There’s a really reductive, but not entirely inaccurate, way of explaining why older actresses have historically been sidelined in Hollywood while a constant stream of young, fresh women are cycled in. And for most of its history, Hollywood has been run by men, and movies are, as a work of both art and commerce, a medium that plays on fantasies, and the men who run things fantasize about having sex with young, unspoiled women, not women who are the age and have the maturity and life experience of their own wives. This is part of the story, but if it was the whole story, stars such as Crawford, Davis, and Barbara Stanwyck, would never have survived on screens for as long as they did—and both Davis and Stanwyck were able to work even longer than Crawford, because in the 1970s and ’80s, they successfully transitioned to television. These female stars stuck around because they didn’t just appeal to the male gaze: They inspired fantasies in women, and they were able to continue to do so long after male producers and male viewers had moved on to fetishizing the new crop. They did this by modeling to women a way of being that many viewers could not have pulled off in their real lives, because it would involve not giving a shit what the men in their lives were to say or think.

This was something Crawford was very aware of. “I can tell you one thing Bette and I had in common,” Crawford said, after she had retired from movies. “Our roles put men off.” There was a major difference in how they pulled this off, though. For a while, Crawford had been able to model female fantasies of independence and power while also presenting an image that was attractive to men, but Davis always struggled to conform to the standards of Hollywood beauty. Her reign as a queen of romantic melodrama was propelled less by her inherent glamor and more by the evident work it took her to appear glamorous—thus making her a perfect avatar for the woman in the audience who longed for the adventurous life, or maybe just the easier life, of the born beautiful.

The fact that Davis was on her best day an 8 in a profession in which women are supposed to be a perfect 10 every day was as much a part of her star persona as Joan’s less-than-classy background was part of hers. They were both seen as powerful women who went into the game with a disadvantage, and that in itself took some of the bite off of their power and made them more accessible.

At the same time, Crawford was born gorgeous and worked hard to present an impeccable image of herself for her entire time in the public eye, while Davis was born slightly less gorgeous and eagerly sought parts that allowed her to explore what it was like to be a woman in the world and not have beauty available to her as a weapon. Many of Davis’ most famous catty comments about Crawford seem to stem from a combination of resentment and pride in their difference. She was frequently quoted saying some version of this: “Miss Crawford is a movie star, and I am an actress.” This annoyed Crawford to no end, but she had her own version. When Davis had made a move on Crawford’s then-husband Franchot Tone while they were working together on the film Dangerous, Tone turned Davis down, and this was because, as Crawford liked to say, “He thought Bette was a good actress, but he never thought of her as a woman.”

Certainly there were plenty of men who did think of Davis as a desirable woman, but as both Crawford and Davis got older, even if there continued to be romantic elements to their movies, there was a sense that they were thought to be desirable at an advanced age in part because of a collective memory of who they used to be. This collective memory could be used against them, too, as it was in the one film they appeared in together.

Crawford first worked with director Robert Aldrich on one of her favorite later films, Autumn Leaves. Aldrich had refused to make changes Crawford asked for to the script, which didn’t exactly put him in the actress’ good graces, but Aldrich won her over with his genuine emotional reaction to her work.

Biographers Lawrence Quirk and William Schoell claim that Crawford came up with the idea of casting Davis as her sister and rival in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Aldrich says the casting was his idea but gives Crawford quite a bit of credit. “I never had anyone else in mind but Joan and Bette for the picture,” said Aldrich. “And then Joan talked Bette Davis into being Baby Jane.”

But even if Crawford recruited Davis only on Aldrich’s orders, the fact that she reached out to her suggests that there was no serious tension between the actresses before they made this film, despite the fact that Crawford would have had at least two instances she could have pointed to in which Davis had previously sought to undermine her.

There was Davis’ acknowledged attempt to seduce Crawford’s second husband, and then there was The Star. Released in 1952, The Star was written by Katherine Albert, an old friend of Crawford’s with whom the actress had had a falling out when Crawford persuaded Albert’s daughter to marry a man the mom didn’t approve of. Albert allegedly wrote the screenplay as retaliation, intending it as a thinly veiled attack on Crawford. Not only did it exaggerate Crawford’s struggles to keep her career going past her sell-by date, but Davis was cast as the aging actress in Crawford’s mold.

But Crawford doesn’t seem to have taken The Star as a serious attack. She would forever insist that she had no reason to consider Davis to be a rival—which was itself a way of throwing shade. As Crawford explained it, she and Davis spent most of their careers playing different kinds of roles. This was true, and the difference could be spun either way.

If anything it seems like it was Davis who was concerned about Crawford undermining her on set. She would have had a right to be concerned—she surely would have heard stories of Crawford’s rivalries with other actresses on the set of Johnny Guitar and other movies. Before she agreed to make the film, Davis met with Aldrich and asked him whether he and Crawford were sleeping together: “It wasn’t that I cared about his private life, or hers either. That’s a matter of taste. I didn’t want him favoring her with more close-ups.”

He definitely did not. What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? plays out along lines similar to other horrors-of-Hollywood stories, particularly Sunset Boulevard, but it’s at once more epic and more claustrophobic. It begins in 1917. Baby Jane Hudson (Davis), a prepubescent, ringleted blonde with a grating little-girl voice, is a vaudeville sensation, and the nearly life-size dolls made in her image are selling like hotcakes. Jane has a precious daddy’s girl onstage persona, but off stage she’s a terror—mean and greedy and selfish.

We don’t know if Jane was born bad or if show business made her that way. Likewise, we don’t know if her jealous sister Blanche (Crawford) would have otherwise taken so easily to the role of victim with steely resolve if it hadn’t been foisted upon her. The film to come will spin on the discrepancy between the real Jane and Blanche and the versions of themselves that they perform, which gets further layered thanks to what we think we know about the stars that we bring with us to the viewing experience. The movie’s opening shows the way show business commodifies youth and bestows superhuman power on star but also the mistake made in treating stars like they’re different from normal people—because once they cross that line, they don’t know how to go back to being normal people.

The movie then jumps 18 years into the future. Adult Jane and Blanche are now both movie actresses, but Blanche is a star, and Jane is a flop. Male movie executives discuss the sisters, as they watch actual footage from some of Davis’ early films. Later, Blanche, now crippled from the accident we saw glimpses of just before the credits, watches a movie alone in her room, spellbound at the sight of her younger self. The film within the film here is Sadie McKee, one of those 1930s melodramas in which Crawford’s then-husband Franchot Tone waits around the whole movie for her to decide to love him. Given Crawford’s continued affection for Tone, and the commentary Blanche gives regarding the director, this seems to me like the moment in the film where the line between Joan and Blanche dissolves the most completely.

To say too much more about what happens in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? would be to spoil the pleasures and horrors of watching the film. Before watching it in the research for this episode, I hadn’t seen the film in 20 years, and it was completely different from my memories. I had remembered it as a lot of people seem to think of it—as something to be appreciated through the lens of camp. But I don’t think that’s a fair interpretation of the movie, which throughout its two-hour-plus running time is consistently complex in the way it depicts both sisters, the damage they do to each other, and the insanity inspired by fame. Crawford has arguably the more difficult part, because she’s passive all the way through the film; at the end, she makes a shocking, devastating confession, but by that time her character is dying and is so weak that Crawford has to convey the most hurtful thing she’s ever said to her sister through a barely audible croak. Davis got the Oscar nomination, and that’s probably because she did the most acting, but even so, you can’t dismiss her performance as pure excess. There are times in Baby Jane that you actually find yourself rooting for Jane to get away with something, and it’s only then that you realize the extent to which Davis managed to humanize what could have been a purely grotesque character.

I haven’t been able to find any credible stories of incidents on the set of Baby Jane that would suggest that the actresses were at each other’s throats during filming. And there is one important fact that should have compelled each actress to remain on her best behavior: Even with both Davis and Crawford on board, Aldrich had trouble finding a studio that would finance the movie. Finally Seven Arts agreed to take Baby Jane on, but only a deal that included almost no upfront payment for the principles, in exchange for hefty percentages once the film turned a profit. Because of this deal, Davis and Crawford—neither of whom were getting any younger and neither of whom were in a position to sneeze at a payday—both had an incentive to make Baby Jane the best and most successful it could be. The stories I have read about their relationship suggest that both actresses fused aspects of their characters in the film with their real lives and continued playing those characters after filming, maybe in part because they thought it would be good for the movie, and maybe just because they liked it.

For her part, Crawford claimed she had no sense whatsoever of a rivalry going into the shooting. “I can’t speak for her,” Crawford would later say, “I can only speak for myself, and doing that, I can only say, I didn’t have a feud with her.” If there was animosity between them, Crawford insisted, it wasn’t her fault. Crawford claimed that she had tried to be friends with Davis, and by way of initiating that friendship, she had sent Davis chocolates and flowers at the start of the film and received no response.

When asked about this, Davis basically rolled her eyes and was like, “That is so Joan Crawford.” Davis thought this attempt was disingenuous, and she had grounds to feel that way. Crawford’s image as a strong, often solitary woman on screen, though often at odds with the vulnerability and shyness she felt off screen, had one important parallel with her real life: Crawford, like her characters, didn’t have a lot of close female friends. She was close to Stanwyck—so close that some observers believe they were lovers—and also with Myrna Loy. But these friendships were never really tested through the arduous production of a movie—none of Crawford’s female friends ever had to share the spotlight with her. If they had, they might not have been her friends anymore.

Davis thought that Crawford’s very act of giving gifts was, in her words, insincere, and in her mind, it was so typical of Crawford, who Davis thought was concerned with appearances to a fault. Davis was proud of how bad she had allowed herself to look in Baby Jane. She’d point out that Crawford had chosen the less grotesque part, as though this was a character flaw on Crawford’s part.

Crawford’s tactic when speaking about Davis was generally to act as though she never gave the other actress a thought, whereas Davis never seemed to tire of commenting on or directly criticizing her Baby Jane co-star. Davis told her and Crawford’s mutual biographer, Charlotte Chandler, that she kept picking on Crawford “because she had absolutely no sense of humor. … I noticed poking some fun was a good attention-getting device, and I was never adverse to getting a little extra attention.”

When I read this quote, after having already read many more from both Davis and Crawford on the other, another celebrity feud came to mind, a much more contemporary one. Davis is basically Kanye West, who can’t resist dragging Taylor Swift into his art, in part because he knows she just cannot stop herself from reacting to it, and this keeps both of them in the spotlight. And Crawford, not understanding the game Davis was playing, just kept being like, “I’d rather prefer to be excluded from this narrative.” When all was said and done, Crawford insisted that she respected Davis more than she hated her. “She can be such a bitch,” Crawford said late in life, “but she’s so talented and dedicated and honest.”

The feud, such as it was, was encouraged by the studio’s publicity department. According to Crawford, the actresses failed to give the PR men much to work with on set: They weren’t best friends, but they kept their claws to themselves.

The animosity definitely intensified after filming was finished, beginning with the announcement of the Oscar nominations. Davis was nominated, and Crawford was not, and what Crawford did next was perceived by many as an attempt to right that wrong. Crawford approached every nominated actress and offered to accept her statuette if she was unable to accept. No one thought that this in itself was anything but generous at the time, Davis included—she assumed that she would win, and she was certainly not going to be absent on the evening in question, so what did she care? What she perhaps didn’t know was that Anne Bancroft, who was nominated for The Miracle Worker but couldn’t attend because she was appearing on Broadway at the time, took Crawford up on the offer. And, as it turned out, Bancroft won. Later, Davis partisans would allege that Crawford had actively campaigned for Bancroft, to ensure that Crawford would be in the spotlight on Oscar night, while Davis sat helplessly watching.

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was such a huge, immediate hit that it recouped its costs after 11 days in theaters, and both Davis and Crawford, who had deals entitling them to a share of the profits, made a lot of money. It was a much needed victory for both women. Just two months earlier, Davis had put an ad in Variety soliciting work.

“Thirty years experience as an actress in motion pictures,” it read, in part. “Mobile still and more affable than rumor would have it. Wants steady employment in Hollywood. (Has had Broadway).”

After Baby Jane, both Crawford and Davis found themselves in demand for a new wave of horror thrillers. Aldrich even approached Crawford and Davis about starring in a film that would aim to repeat the success of Baby Jane, called What Ever Happened to Cousin Charlotte? The plot would have the actresses reversing their previous roles: This time Crawford would be the manipulative aggressor, conniving to turn Davis’ Southern spinster mad in order to take control of her estate. Crawford was keen to do it—she still needed the money—but in order to get Davis to sign on, Aldrich had to agree to make her a producing partner, and Crawford believed Davis tried to exclude her from the beginning. Crawford was paranoid that Davis and Aldrich were sleeping together—just as Davis had been regarding Aldrich and Crawford before Baby Jane—and her suspicions that she was being given the opposite of the star treatment at Davis’ request was given some credence when for some reason no one was sent to pick Crawford up from the airport when she arrived in Baton Rouge for a location shoot.

It only got worse from there. Davis was, probably rightfully, still annoyed by what she perceived as Crawford’s manipulation of Oscar night, if not the Oscar voting, and in retaliation Davis apparently started trying to divide the cast and crew into a Davis camp and a Crawford camp. Crawford had trouble holding on to even her natural partisans, crew members with whom she had been friendly for years, because by 1964, her insistence on carrying herself and being treated like the duchess of the MGM lot seemed so ridiculous. Davis had begun contemptuously referring to her as “Miss Crawford.”

On the last day of the location shoot, everyone packed up and went back to the hotel—and left Crawford on set in her trailer. Crawford believed that this was a cruel joke played by Davis, who she also believed was essentially directing the film herself, or at least maneuvering to have Crawford’s part cut to a minimum. Whether she was doing any of this stuff or not, Davis was essentially successfully doing what was done to her character in the movie: driving the other woman mad, in order to get rid of her. Crawford returned to Los Angeles and checked herself into a hospital. Though various physical ailments were used as excuses for the studio, Crawford wasn’t really suffering from much other than the exhaustion that went along with humiliation. She had spoken to a lawyer and knew she couldn’t get out of her contract to do the movie, so she essentially decided to hide out in a safe space from which they couldn’t force her to work, but where she could be in touch with Aldrich and try to get him to make changes to the script. It seems like this hospital stay began as a power move, but at some point, Crawford became convinced she was really sick, and that the doctors just couldn’t figure out what the problem was. She returned to the set but said she could only work a few hours a day and needed to spend the rest of her time at home resting. Aldrich had her followed to make sure she was really at home resting. Then she checked back into the hospital, forcing production to shut down. Crawford apparently assumed that if she stayed in the hospital long enough, the production would have to be shut down for good.

This was, indeed, what would have happened, if Aldrich had allowed it to. Instead, during this second hospital stay, Aldrich and company decided they had had enough and recast Crawford. Olivia de Havilland, who had appeared in several films with Davis before marrying a Frenchman and moving to Europe, was persuaded to step into Crawford’s shoes. Aldrich himself flew to Switzerland and spent four days pleading his case before de Havilland agreed to go to work. Crawford alleged that no one—not Aldrich, not anyone involved with the production—had told her that she was replaced. The director, she railed, “didn’t even have the balls to come and tell me to my face or even over the phone! I had to hear it over the radio!”

After she had retired from the screen, Crawford disowned every film she made after Baby Jane. “They were all terrible, even the few I thought might be good,” she later said. “I made them because I needed the money or I was bored or both.”

Crawford made her last film, the B-Horror Trog, in 1970. She spent the last seven years of her life living alone in a New York City apartment, rarely making public appearances, although she did venture out for the occasional lunch with friends, and she did allow several journalists to visit her. One of those journalists asked her about the rumors he had heard that she had a drinking problem. Crawford answered with remarkable candor.

Yes, I have a drinking problem. … I really think alcoholism is one of the occupational hazards of being an actor, of being a widow, and of being alone. I’m all three. … I like to think it started after Alfred’s death, but I’m afraid it began well before that, when I used to fortify myself before a Pepsi sales meeting or one of the luncheons or dinners we either gave or attended.

“But when does a problem get to be a problem?” she added. “I’m afraid I crossed over the line when Baby Jane was being shot.”

To hear the rest of the story, listen to You Must Remember This Episode 91, “Six Degrees of Joan Crawford: Bette Davis and Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?”