This article is part of A Year of Great Books, a Slate Academy. Laura Miller and John Dickerson will discuss Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov on the Year of Great Books podcast in January. To learn more, read Laura Miller’s introduction to the series, or visit Slate.com/GreatBooks.

The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s last, longest, and most celebrated novel, describes life in a world undergoing deep, unsettling change. It’s a novel of argument and conversation, filled with a staggering variety of voices, each one talking about what it means to be Russian and to be a human being seeking meaning in a bewildering universe. It’s also a family drama, a murder mystery, and a love story. No wonder that so many generations of readers from every walk of life have found in Dostoyevsky’s masterpiece both a reflection of their own big questions and a rich, fascinating world of its own.

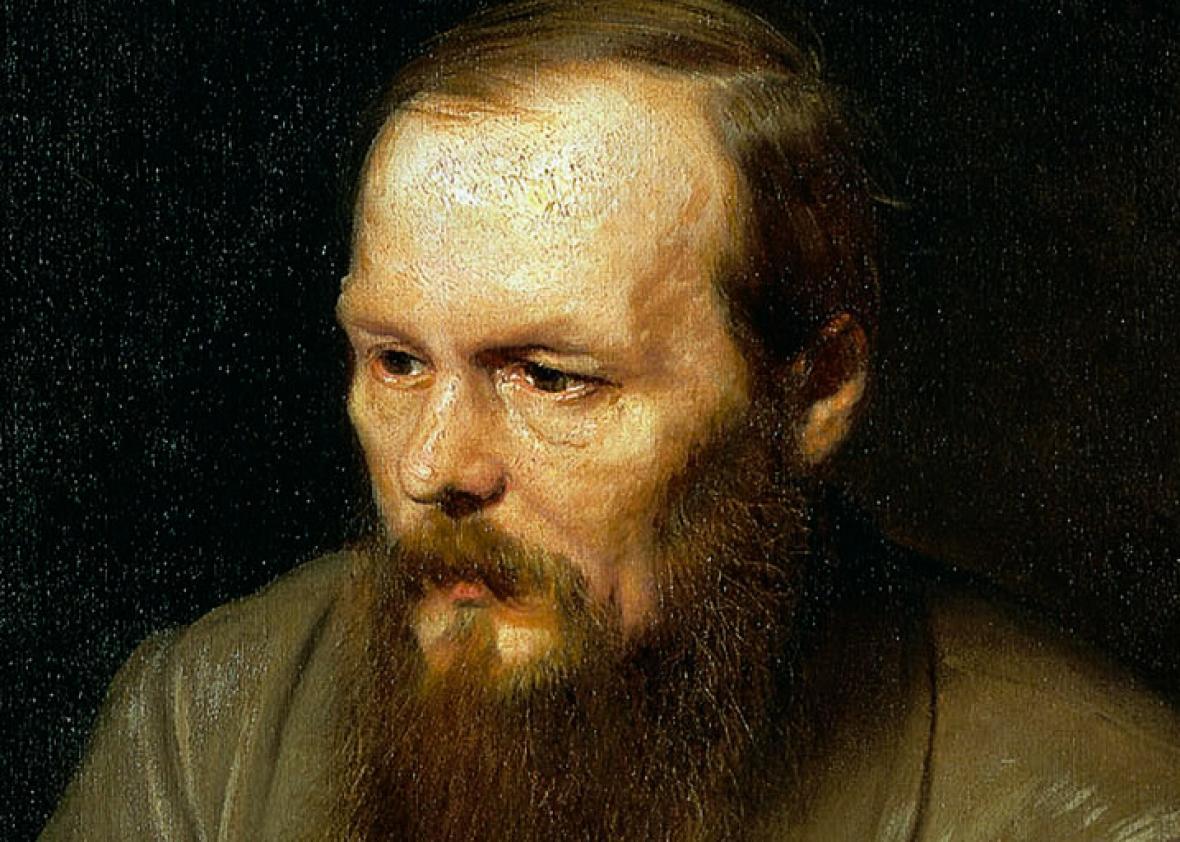

The author of The Brothers Karamazov himself lived a tumultuous life, fragments of which often turn up in his fiction. The son of a physician raised by his own enterprise to the lower rungs of the nobility, Dostoyevsky struggled financially throughout most of his young adulthood, trying to keep up appearances on a limited income. He was idealistic but also impulsive and quick to take offense, qualities he shares with the irascible unnamed narrator of Notes From the Underground. In his 20s, as an up-and-coming writer in 1840s St. Petersburg, he became involved with the utopian socialist Petrashevsky Circle. While the group limited its activities to reading, writing, and discussing political change, it did so against a background of political upheavals across Europe, known as the Revolutions of 1848. Those events spooked the czarist regime, and Dostoyevsky and his fellow intellectuals were rounded up by authorities in 1849 and sentenced to death. Their executions were halted at the last minute by a commutation from the czar—in fact, they were never really meant to be carried out. Almost 20 years after this mock execution, Dostoyevsky would write The Idiot, whose protagonist, like his creator, is permanently scarred by a similar incident of psychological torture.

Equally formative were the four years of hard labor Dostoyevsky served in a brutal Siberian prison camp, where he renounced his rational socialism and embraced a Christian humanism infused with an almost mystical faith in the Russian soul. Ivan Karamazov, the character whose turmoil lies at the heart of The Brothers Karamazov, faces a similar crisis. Dostoyevsky’s Russia was transforming itself from a feudal system to an industrial one, a change that most of Europe had accomplished over the course of centuries rather than decades. Ivan represents the Westernized Russian, an atheist with his eye on the future. His older brother, Dmitri, is a heedless sensualist who lives for the present; Dostoyevsky came to believe that his sort of degraded materialism was the inevitable result of the European Enlightenment championed by intellectuals like Ivan. The third and youngest Karamazov brother, selfless Alyosha (named after Dostoyevsky’s son, who died at age 3 after a seizure caused by the epilepsy he inherited from his father), understands the value of the past and embodies true hope in the form of the ideal man.

There’s a lot that modern readers might find hard to relate to in the moral schema of The Brothers Karamazov. Not only did Dostoyevsky believe that Christianity provided the best solution to the crisis facing Russia, Europe, and humanity itself, but he was convinced that the Russian Orthodox Church was the only true representative of the faith and destined to save the world. Even readers who identify with Ivan’s crisis of hope will probably draw the line at his author’s proposed remedy. Yet none of this has diminished the novel’s power or popularity over the decades. The ferocious, idiosyncratic vitality of Dostoyevsky’s fiction captures readers again and again. So do his indelible characters.

From the novel’s earliest scenes introducing the Karamazovs—the brothers and their drunken, obnoxious father—Dostoyevsky acknowledges that ideas can’t exist without people and that people are the true subject of any novel. Those scenes are both a searching debate about faith and virtue and a sequence that’s recognizable to anyone who has ever spent the holidays with collection of family members ranging from the endearing to the intolerable. It is also, if you ignore Dostoyevsky’s reputation for seriousness, very funny. (“Life is full of the comic,” he once wrote to a friend, “and only majestic in its inner sense.”) If Ivan’s existential confusion doesn’t speak to you, the Karamazovs’ complicated love lives, both sordid and transcendent, never fail to fascinate. Their problems, however grounded in their particular moment in Russian history, seem only a hair’s breadth away from our own. How powerful is love? Hate? Blood? Money? Faith? What makes this great novel immortal is not its answers but its questions, questions we continue to ask ourselves, decades after the world that forged The Brothers Karamazov has passed away.