Anthony Trollope’s Barchester Towers is the next selection for A Year of Great Books, a Slate Academy. To learn more, read Laura Miller’s introduction to the series, or visit Slate.com/GreatBooks.

Our friends at Audible have another gift for Slate Plus members: a complimentary audiobook of Barchester Towers.

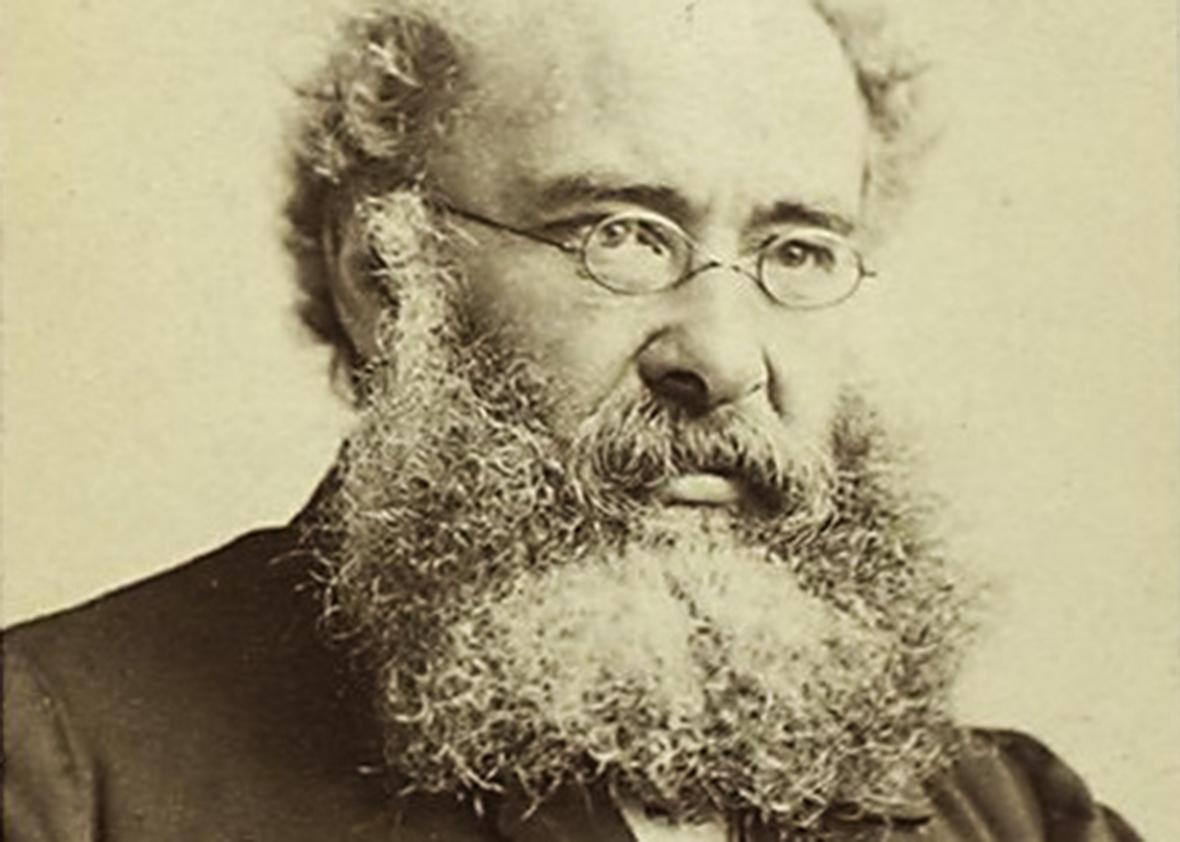

Tolstoy and Henry James loved his novels, but most of the many, many people who avidly read the work of Anthony Trollope today don’t owe their passion to a college professor or highbrow critic. His novels are rarely assigned in courses, and officious parroters of conventional wisdom are forever remarking that he’s not up to the standard of other Victorian classics. Yet you can find thriving Trollope societies on both sides of the pond and die-hard fans in seemingly every walk of life. The reason for this is simple: the vast amount of sheer pleasure readers get from his novels.

Barchester Towers, the second in a loosely connected series of novels called The Chronicles of Barsetshire, provides an astonishing quantity of delight for a book whose subject is the petty power struggles within the ecclesiastical circle in a fictional cathedral town. There’s a high-church faction, invested in the grand and traditional modes of worship and observance, and an invading low-church contingent that advocates greater reformist piety—like prohibiting travel on Sunday, the pet cause of the new bishop’s wife, Mrs. Proudie, and her insinuating chaplain Obadiah Slope, the novel’s villain. But, as most readers quickly realize, the actual bone of contention doesn’t matter much; it’s the contention itself—and above all how the various characters engage in it—that powers the novel. Barchester Towers is, in essence, a workplace comedy.

The Trollope of Barchester Towers is about as worldly as a novelist can get without tipping over into outright cynicism. (The Way We Live Now illustrates how he saw things at a later, less sanguine stage in his life.) Like Jane Austen, he understands human beings to be motivated by a balance of principle and self-interest and that too much of either is equally likely to lead to trouble. The preceding novel in the series, The Warden, describes the scandal surrounding the decent old gentleman Septimus Harding, whose position running a charitable retirement home becomes the subject of a reform campaign.* It’s impossible not to want Mr. Harding to keep his position as warden, but it’s equally impossible not to see that the people who want to take it away from him have a point. In Barchester Towers, Mr. Harding hopes to regain the wardenship, but Mrs. Proudie and Mr. Slope want to give it to a poor clergyman with 14 children, who obviously needs it more. We root for the low-church faction to fail because they’re self-serving and unkind while Mr. Harding is sweet. And so Trollope enlists his readers in the tricky, ambiguous task of making moral sense of the scuffles of everyday life.

Another of Mr. Slope’s projects entails the whipping-into-shape of those clergymen who are supported by church sinecures and “livings” but who don’t do any work. One of them, the Rev. Dr. Vesey Stanhope, is forced with his family to return to Barchester from Italy, where he has been collecting butterflies for the past 12 years. With him come his three adult children, including the inimitable Signora Neroni, a devastating flirt who, as a result of a riding accident, must be carried into rooms and arranged picturesquely on sofas. The Stanhope siblings are reprehensible people—irresponsible, flippant, lazy, and heartless, despite their amiable, obliging temperaments. But the reader’s heart lifts every time they appear on the page, because they’re witty, charming pot-stirrers who promise, deliciously, to vex the schemes of Proudie and Slope.

Although never celebrated for the beauty of his prose, Trollope has no rival as a creator of characters. “He seems not to have invented them but to have found himself in their company,” wrote the critic John Bayley, adding that he “knows them as a wife was once said to know her husband, or a valet his master. He knows them from the inside out, from the weak, uncertain interior to the armored persona that has grown up for public use.” The only remedy for this particular species of disillusionment is fondness and humor, and no one can beat Trollope on that front. He always stops short of mere caricature, and key to the subtle bite of his famous irony is that, good or bad, his characters’ follies are often a discomfiting reflection of our own. “Considering how much we are all given to discuss the characters of others,” he observes in Barchester Towers, “and discuss them often not in the strictest spirit of charity, it is singular how little we are inclined to think that others can speak ill-naturedly of us, and how angry and hurt we are when proof reaches us that they have done so.”

This endlessly amused and ultimately forgiving attitude toward humanity and its flaws—the ways we fail to live up to our ideals and occasionally surprise ourselves and others with our goodness—lacks the visionary grandeur that some people demand of literature. (Trollope’s posthumously published autobiography, which included a matter-of-fact account of his daily work habits, also offended anyone who preferred to think of novels as mystical gifts of the muse.) For the better part of a century, his reputation among scholars and critics languished. But Trollope has always been read—devotedly, hungrily, lovingly—and it is all those readers, alone in their rooms with a book but also immersed in worlds as varied and familiar and perplexing as the one outside their doors, who have had the last and longest laugh.

*Correction, July 7, 2016: This article originally misspelled character Septimus Harding’s last name. (Return.)