This article is part of A Year of Great Books, a Slate Academy. To learn more, visit Slate.com/GreatBooks.

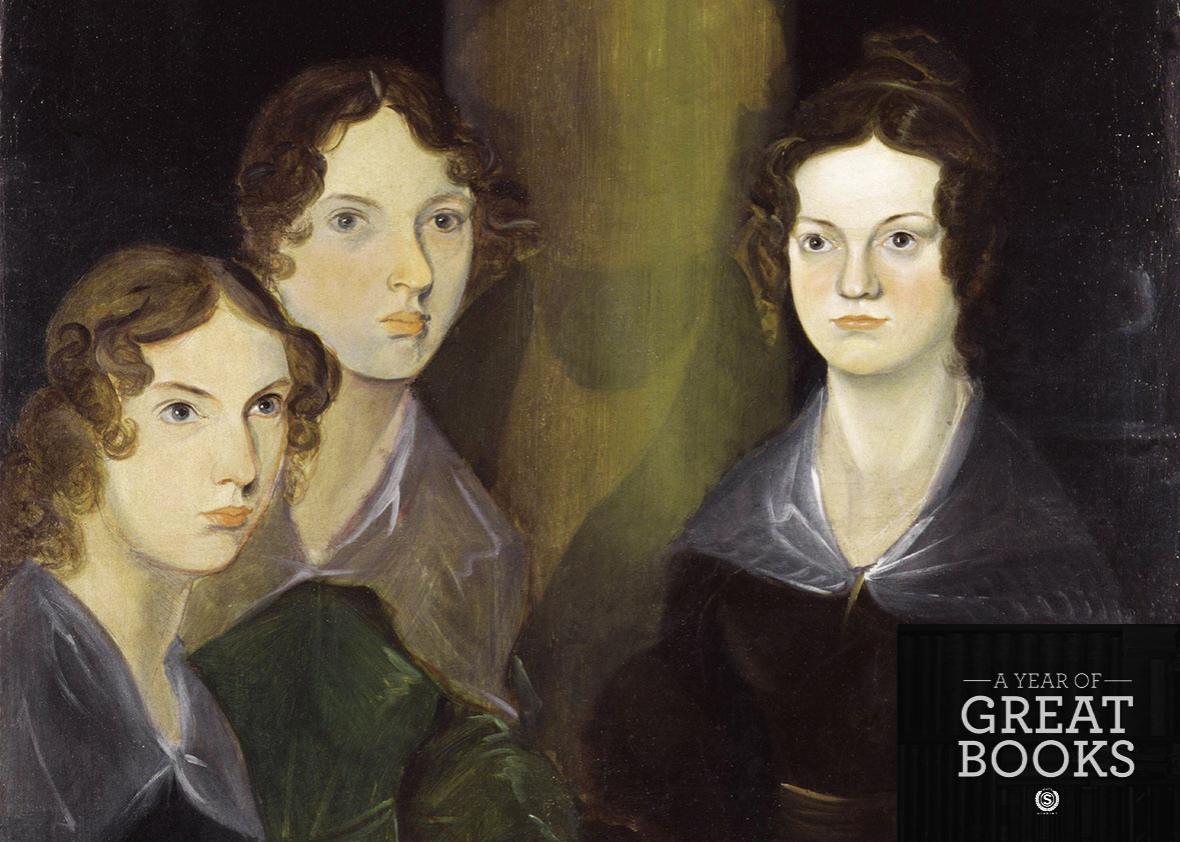

Even before Charlotte Brontë’s death in 1855, Victorian-era readers had started to make the pilgrimage to the Brontë family’s home in Haworth, England. The flow of visitors, and the fascination with the Brontë siblings, continues today.

In The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects, Deborah Lutz explores the childhoods of Charlotte, Emily, Anne, and their siblings through the objects in the Brontë’s family home. Slate books and culture columnist Laura Miller spoke to Lutz, the Thruston B. Morton professor of English at the University of Louisville, on her podcast about Jane Eyre, the second selection in Slate’s Year of Great Books series.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Miller: When they were very young, Charlotte, Anne, Emily, and Branwell, their brother, made these tiny books about imaginary worlds that they created among themselves. What was their childhood like?

Lutz: Their mother died of cancer when they were all very young, a very painful, long, drawn-out death. Anne was still a baby. Their father was a clergyman and didn’t have a lot of money, so it was difficult for him to raise these children.

The children had a lot of free time. They had access to many books and were incredibly imaginative, and they were all close to each other. So they had this childhood of incredible productivity and creativity.

Many of these little manuscripts and books that they created as children still exist. When you read their juvenilia, it’s so clear that they were practicing for their later writing life. You can see many of the scenes and the characters already developing when they were writing when they were 12, 13 or 14.

Miller: Aren’t they like the size of a matchbook?

Lutz: Exactly. You need a magnifying glass to read most of them. Imagine them writing this tiny, tiny script, with quill pens dipped in ink, that only they could see.

It would be hard for the adults to read. In some sense they were creating these little secret stories that were hidden even though they were being written.

Miller: I love that picture of them, all huddled over these little artifacts of their imaginary world.

One thing that’s really striking about the writing of Jane Eyre is that it seemed to be happening around the same time as the writing of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey. Given that they often collaborated on the little books of their imaginary world, has there ever been much attention paid to how they collaborated or influenced each other?

Lutz: Yes, definitely.

The way the sisters became published writers is that they decided to publish their poetry together in one volume. The story goes that Charlotte discovered a manuscript of Emily’s poetry and said, “Emily, we have to publish our poetry together.” And Emily said, “No way. I can’t believe you violated my privacy and read my poetry.” Eventually, Charlotte convinced Emily and Anne to publish a book together. They paid for it themselves and it sold two copies.

But it got them excited. They each decided to write a novel: Emily wrote Wuthering Heights, Anne wrote Agnes Grey, and Charlotte Brontë was working on The Professor, which she first called The Master.

There’s a famous story about the three of them pacing in the dining room or parlor at night, discussing the writing they had done during that day, reading parts of their drafts to each other, commenting on each other’s drafts.

So I do think the novels were collaborative, in a way.

But we also have a lot of evidence that they didn’t agree on what each other were doing. Emily and Anne couldn’t believe that Charlotte made Jane Eyre plain. They said, “How could you do that? You must have a beautiful heroine, like Catherine Earnshaw in Wuthering Heights.”

Another point that kind of gets forgotten is that Wuthering Heights was written before Jane Eyre. I can’t prove this, of course, but I have a strong opinion that Jane Eyre is really a commentary on, and to some extent derivative of, Wuthering Heights. Rochester is like a second Heathcliff.

Miller: Aren’t both characters based on Byron?

Lutz: Yes. They’re definitely based on Byron, George Byron’s Byronic heroes, as they’re called. Those gloomy, moody, idealistic, but kind of fallen, cynical men.

Miller: Always with dark hair.

Lutz: Exactly. And a brooding brow and dark eyes.

I’m not saying, necessarily, that Charlotte had never thought of this kind of character before she wrote Rochester, or before she encountered Heathcliff.

We do also see a lot of those characters in their early writings.

But I still think that there was a lot of influence, because Charlotte was unable to get The Professor published. It wasn’t published until after she died and had become famous writing Jane Eyre. It’s more of a realist novel and less gothic than Wuthering Heights. And I do think that Charlotte read Wuthering Heights and thought, “OK, look at what she’s doing with the gothic here. I want to do this myself.” That was Jane Eyre.

I do think that the one influenced the other pretty heavily.

Miller: Your book relates a remark that one of the Brontës’ neighbors made, that the siblings spent so much of their time outdoors. They were all big walkers. Emily was famous for loving the heaths, or the moors.

Lutz: They did spend so much time out walking.

Emily, especially, used her walks out in nature to write her poems. Many of her poems, you could just call them accounts of her walks. They’re about her experience with nature, about the magical elements of nature. They’re about birdsong and the craggy heath and all the trees.

Miller: In our online discussion of Jane Eyre, we talked a lot about religion and nature. In that crucial moment where Jane’s about to succumb to St. John’s effort to get her to go off and be a missionary, she has this sort of visionary experience. It’s depicted as something that’s coming from the natural world, that’s telling her that she needs to go back to Mr. Rochester.

Lutz: Yeah, there is a sympathy with nature, almost a mystical relationship, that develops in Jane Eyre.

There’s a beautiful scene when Rochester and Jane meet that’s gothic and fairy tale–ish. But it also has a natural element. It’s dusk, in the gloaming, and he comes up with this big dog that looks like a shape-shifter. Then he slips on the ice.

It’s almost as if nature helps along their relationship.

Miller: Right.

One of the things that surprised me in re-reading the book was that there’s so much religion in it, which I just skimmed over when I was very young and was really identifying with Jane. But in a weird way the nature element is kind of a counterbalance to that.

It’s like a religion, and it is the thing that calls her away from St. John.

Lutz: That’s a good point. Obviously, in Jane Eyre, Charlotte is very ambivalent about religion. There’s a number of critiques of religious figures.

There’s Mr. Brocklehurst, the headmaster at Lowood. That’s a critique of a certain kind of evangelical Christian. Helen Burns, Jane’s friend at Lowood, is also a Christian of a different stripe. I think that Charlotte is much more sympathetic with Helen’s version of evangelicalism—but still, I think Jane makes it clear that it’s not for her, that kind of going up to heaven and forgetting the earthly life.

Miller: The resignation of that character.

Lutz: Exactly. It’s also interesting when she ultimately rejects St. John and the missionary life.

She ends up at Ferndean Manor. And Ferndean Manor is full of this kind of magical, fairy-tale, nature imagery, right? It’s deep in the dark woods. It’s connected to ferns, these moist, slightly erotic plants that grow in the shadowy places. It’s almost like a dark Eden. And they sort of retreat from society into their couplehood, in this natural place.

Of course, the very end of the novel is St. John speaking about Jesus. So it’s complicated.

Miller: There are definitely writers who have been worshipped and admired, and people visit their houses, but the Brontës almost seem in a class by themselves. There’s almost a religious—as you put it, they’re like saints, and there’s this kind of investment of everything that they touched and used and the place where they lived with this kind of magical or sacred power.

Why do you think that is?

Lutz: I think it’s complicated. First I’ll say that the Victorians liked to do that. Many Victorians idolized certain authors. Literary stars became kind of secular saints for tourists to go visit, to try to get a little leaf off of the tree that grew near Tennyson’s house.

But I think with the Brontës it was special. I think that people very quickly associated the town that they grew up in, Haworth, and the parsonage, the place, with their novels. People would go there and think about being in parts of Jane Eyre, like they were in the novel somehow. The moorish, sort of gothic feeling that you get when you go there—I think that’s part of it.

Also Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë was incredibly popular.

Miller: That was published how soon after Charlotte’s death?

Lutz: Very quickly, two years after she died.

Of course she published all of her novels under a pseudonym, Currer Bell. Toward the end of her life, people did make the connection between Charlotte Brontë and Currer Bell, that’s for sure. Already relic hunters were coming up to see her during her lifetime.

But she died in the height of her fame, and people didn’t know much about her, and then that biography came out. Not only did it increase the cult of Charlotte Brontë, but it also became a best-seller.

One thing that it did, it talked in such an intimate manner about Charlotte Brontë as a woman, as a domestic woman. I think the domestic objects surrounding Charlotte Brontë became again closely connected with her as a writer, with her as a person, with her body, with her books.

Miller: And it lasted. The parsonage and the area around it is still a huge tourist attraction.

It seems to me like it’s also something about the idea of their childhood together, the idea of these geniuses all together in this almost fairy-tale setting. It plays into a more contemporary idea of what the creative life is supposed to be like.

Lutz: I agree. They were such geniuses, they were siblings, and they lived in this strange, gloomy, beautiful place. And they died young—I think that really strikes the imagination, especially today.

Miller: What about Jane Eyre—what do you think its lasting power comes from?

Lutz: I have a hard time answering that question. It’s obvious that it has a lasting power; I teach it all of the time to my undergraduates, and I’m amazed at the response I get. Women, especially, feel such a strong connection to it.

One thing that’s so wonderful about the novel is that we really feel like we get to know Jane. We get in her mind. She’s an unhappy, angry child. Perhaps young women feel connected to that. It’s a powerful romance/love story, but it’s also a feminist tale.

I guess I’ll say there’s a lot in there. I don’t find that mysterious because I feel it myself.

And I don’t see it abating. I just see it increasing. New generations of people are being born, and they grow up, and they themselves discover the Brontës and love the Brontës. There’s something lasting, really lasting, about it.

Miller: Maybe it’s that primal quality that both of the books have that doesn’t go away. They’re not really about a society, or a particular set of manners, the way that, say, a Trollope novel is. They’re about things that everyone experiences in a certain way, whether they live in the 19th century or the 21st century.

Lutz: I think the primal quality is very true.

In researching the conception and writing of Jane Eyre, you get the sense that Charlotte just wrote it all out in a big rush. It’s almost like it came rushing out of her unconscious mind. There’s something really raw about it.

And she didn’t want to go back. Her publishers wanted her to revise it in a more complete, major way. She said, “no way,” basically. That was a bold stand for a new, unpublished writer.

I think she felt like: “This is what it is. It came straight out of me, and this is how it’s going to stay.”

To access all features of this Slate Academy, or to learn more about enrolling, visit Slate.com/GreatBooks.