This article is part of A Year of Great Books, a Slate Academy. To learn more, read Laura Miller’s introduction to the series, or visit Slate.com/GreatBooks.

Tristram Shandy, like the book that bears his name, is a failure. His body is too long, his nose too short, his lungs weak, his animal spirits unpredictable. He laments the folly of making plans, makes them in the following chapter, scuttles them in the next. In the tenderest and most intimate of terms, Tristram seeks proximity to his readers, yet his book is a virtuoso performance of miscommunication: It is radically “reader-friendly”—Tristram confides to his audience, invites us to speak, leaves us an empty chapter to draw in—and at the same time impenetrable. It is an incomplete autobiography, a distracted monologue, an almanac with no practical use, and—physically—a brick. The novel is a monument to malfunction, and a surprisingly effective guide to laughing it off.

Is that just a fancy way of excusing Tristram Shandy for being weird and unapproachable? Maybe. But it’s also a way to understand Sterne’s balance of folly and philosophy. Tristram takes perverse delight in the comedy of fragments and failure; to do so is, for him, almost an article of faith. In his dedication to William Pitt the elder, Sterne asserts that “every time a man smiles,—but much more so, when he laughs, that it adds something to this Fragment of life.” For Sterne, comedy is all about fragments, interruption, and non sequitur, and for Tristram, laughter is where lofty enterprise meets essential impotence.

At the close of the second volume, Tristram writes:

With all my hurry and precipitation, I have but been clearing the ground to raise the building—and such a building do I foresee it will turn out, as never was planned, and as never was executed since Adam.

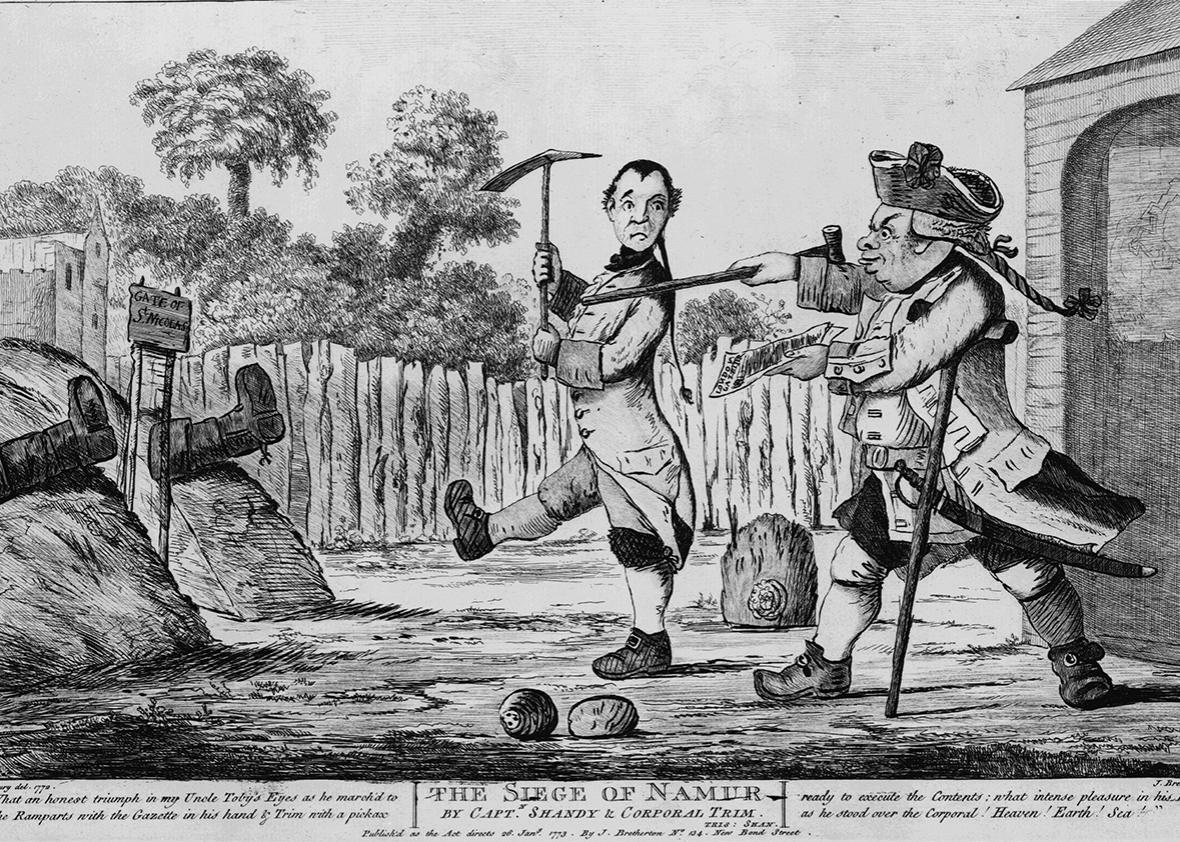

It is not a spoiler to tell you that Tristram’s “plan” for his autobiography does indeed go awry, an outcome that in a wiser moment Tristram acknowledges as inevitable: “Now consider, sir, what nonsense it is, either in fighting, or writing, or any thing else (whether in rhyme to it, or not) which a man has occasion to do—to act by plan.” In fact, there’s a strong suggestion throughout the novel that plans and systems are downright immoral—an exercise in pride (see: Shandy, Walter) that can be thwarted only by humility (see: Shandy, Toby).

Just consider the shoals on which our hero founders. Traveling through Europe, Tristram loses the “best” pages from his journal, “the wisest—the wittiest.” Elsewhere, he wonders at his own mounting failures as chronicler, and essentially admits that he takes perverse “pleasure in running into difficulties of this kind, merely to make fresh experiments of getting out of ’em.” Like a mechanical tinkerer, Tristram will set three plots going at once, then step back and marvel at the concurrent “progressive and digressive” strands of his tale. He bemoans brokenness in one moment and celebrates it in the next. The resulting book, he observes, is of “so odd, so mixed and tragicomical a texture” as has never been seen—in other words, the comedy that Sterne prescribes to Pitt as our best consolation against melancholy born of powerlessness.

And that powerlessness is not just metaphysical but physiological. To state it plainly, the Shandy line is noble and old and will probably end with Tristram. He never says as much, and he does make glancing reference to future grandchildren, but it becomes pretty clear that the novel is Tristram’s child, and there won’t really be others. We don’t know for sure what Tristram can and cannot do, manhood-wise, nor how much the window sash or an overenthusiastic horse was to blame. But one moment with Jenny leaves the strong impression that Tristram’s nether parts are less than functional:

—Do, my dear Jenny, tell the world for me, how I behaved under one, the most oppressive of its kind, which could befal me as a man, proud as he ought to be of his manhood—

’Tis enough, saidst thou, coming close up to me, as I stood with my garters in my hand, reflecting upon what had not pass’d—’Tis enough, Tristram, and I am satisfied, saidst thou, whispering these words in my ear,………. ………;—………—any other man would have sunk down to the centre—

No matter; in Shandy, dysfunction is more important as metaphor than as diagnosis. The plot is built on prematurity and interruption and a basic failure to get certain things to work. Tristram sighs that “nothing ever wrought with our family after the ordinary way,” and Sterne evokes sexual failure out of nearly every instance of Shandean absurdity: Uncle Toby tinkers on the bowling green to console himself for the shrapnel in his groin; Walter writes nonsense metaphysics, and when he talks philosophy with his wife, he’s so boring that she literally fakes it:

[My mother] had a way … never to refuse her assent and consent to any proposition my father laid before her, merely because she did not understand it, or had no ideas of the principal word or term of art, upon which the tenet or proposition rolled. She contented herself with doing all that her godfathers and godmothers promised for her—but no more; and so would go on using a hard word twenty years together—and replying to it too, if it was a verb, in all its moods and tenses, without giving herself any trouble to enquire about it.

The dysfunction motif serves several ends: It drives (or stalls) plot while serving as philosophical reminder of human frailty—and as a cutting metaphor for the autobiographical enterprise. In every instance of impotence, prematurity, or dysfunction, Sterne elicits comedy from the most mortifying, and most common, of manly failures—an inability to get up and get going. But the theme is not just a comic one. Sterne’s animating philosophy is to embrace impotence, the condition that defines pretty much every human endeavor. We can call that a tragedy, or we can accept it as the ludicrous but central fact of life. Shandy would have us do the latter.

Walter is opposed to Tristram on this point. He builds totalizing philosophies out of noses and names. The more he plans, the more his plans go awry. Indeed, Walter’s obsession with systems verges on the irreligious. During Walter’s disquisition on the philosophy of Slawkenbergius and the supposed causes of shortness or length in a child’s nose, Uncle Toby sounds the proper Anglican note:

There is no cause but one, replied my uncle Toby—why one man’s nose is longer than another’s, but because that God pleases to have it so. … ’Tis he … who makes us all, and frames and puts us together in such forms and proportions, and for such ends, as is agreeable to his infinite wisdom,.—’Tis a pious account, cried my father, but not philosophical—there is more religion in it than sound science.

Toby is the better man by far, no matter how dim his wits, because he understands that impossible questions and flattened noses and all the other gaps in man’s self-apprehension are part of the deal when you’re mortal. Plans invite retribution; systems that artificially unify a fractured or unknowable truth are more dangerous still. When Tristram calls his whimsical style of writing “the most religious,” he’s making a joke about trusting to providence—but he’s also being entirely serious. In the world of Shandy, you have a choice. You can accept that you live in a world defined by interruption and distraction and failure, or you can submit to a unifying dogma that explains nothing and poisons everything.

The proper Shandean (as Tristram calls his imagined emulators) surrenders to the providence of whim and lives with more wisdom and holiness than a thousand Walters. A Shandean knows that failure can be funny and deferral can be beautiful; that when death knocks at your door you should hop a ship to Calais; that life itself is a bawdy non sequitur; that there is wisdom in fools, and a wise fool is richer than a prince; that a train of thought has no business running straight. Our first duty, as readers, is to laugh. If we laugh long enough, and with an honest spirit, we may at length become the kind of “good, honest, unthinking Shandean people” whom Tristram honors with his book. Go forth, then, mount your hobbyhorse, and do not fret if your spirits slacken or fail. I’m told it happens to lots of dudes.