2016 has been a year of almost unbearable loss. We have lost athletes, artists, leaders, innocent civilians, and some fundamental faith in our country. And of course we’ve lost so many great musicians. Each of these losses, from David Bowie in early January to Leonard Cohen just a few weeks ago, occasioned extraordinary tributes from publications and individuals, floods of love and appreciation from writers, contemporaries, collaborators, and fans. Our social media platforms became impromptu fanzines and mixtapes, collaboratively curated by friends and strangers far and wide.

In the days following Bowie’s and Prince’s deaths in particular, our collective grief also swelled with warmth, the feeling that we were all listening to music together, helping each other through. These were times the internet lived up to its promise to make the world smaller, in the best of ways. But coursing underneath it all was a sense of frustration. How sad it was to know that it took the deaths of the artists we loved for us to stop and feel how much they’d meant to us all along. If only we could have said all this to them while they were still here.

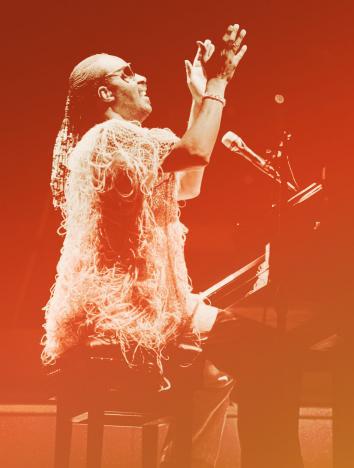

We can. Welcome to Wonder Week, a celebration of Stevie Wonder, one of the world’s greatest living artists and a man whose work encapsulates and inspires the joy and love and miracle of music as much as any we’ve ever heard. There may indeed come a day, hopefully a day a long, long time from now, when Stevie Wonder is no longer with us. (I say “may” because there is a small but extant chance that Stevie Wonder is in fact an actual god.) But for right now he is very much still here, and love’s in need of love today, and so all this week at Slate we’ll be singing his praises, in the words and melodies and grooves that he’s taught us, and we hope you’ll join us.

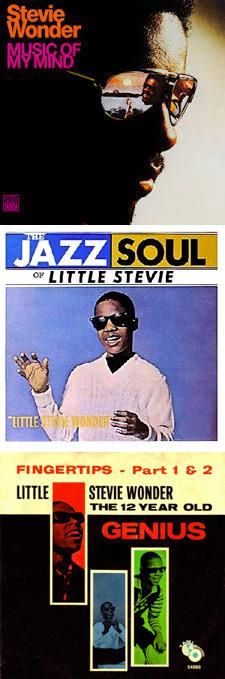

A tour through Stevie Wonder’s career reveals something like the absolute best version of ourselves, as we’d like to be; he grew up alongside modern America as we know it. He was born in Saginaw, Michigan, in 1950, raised in Detroit, and had his first No. 1 hit in 1963, when he was “Little Stevie Wonder,” with “Fingertips, Pt. 2,” a song that isn’t even a song, one of the strangest and most exuberant hit singles in American history. It spent three weeks on top of the charts; one week after it left the top slot Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream Speech” in Washington; three months after that John F. Kennedy was murdered in Dallas. Stevie was 13 and suddenly the decade was no longer the 1960s but the Sixties. During that decade, when Motown Records revolutionized American music, Stevie was one of the label’s prized commodities, scoring eight more Top 10 hits before turning 20.

That eventful period, an entire career for most artists, was but a prologue. In 1971 he turned 21 and wrested creative control of his music (and a much sweeter financial deal) from Berry Gordy and Motown. The following year he released Music of My Mind, an extraordinarily ambitious work that was written, produced, and performed almost entirely by Wonder himself. Thus began Wonder’s legendary “classic period,” the five-year span between 1972 and 1976 that is, in my estimation, the most astonishing run by a solo artist in the history of popular music. During this time Wonder released five albums, won Album of the Year at the Grammys three times, and charted eight Top 10 singles, including five No. 1s.

Wonder also established himself in these years as the premier pop-musical conscience of his generation, an artist who inherited the energies and struggles of the Sixties and bore them with the grace and ferocity of a lion. He wrote some of the most scathing anti-Nixon music of the Watergate era, then in the early 1980s became the musical voice behind the movement to make Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a national holiday. He later gained renown as a passionate anti-apartheid advocate, and his music was banned from South Africa after he dedicated his 1985 Best Original Song Oscar to Nelson Mandela. He is a lifelong, outspoken Democrat, and to this day he continues to put his name and talents behind righteous political causes.

So all this week we’ll be sending Stevie our love, to let him know how much we care. But I don’t want to bore him with it, so I’ll raise the first glass now: I first heard Innervisions, Wonder’s 1973 masterpiece, as a teenager in the late 1990s, and it was a revelation, some magical glimpse upon the heights of beauty and sophistication and artistry that music is capable of reaching. It’s a discovery that has dictated almost everything I have done since. Innervisions remains my favorite album, and Stevie remains my favorite musician, and if he were here standing in front of me right now I would tell him that he changed my life. In the meantime I hope these words find their way to him somehow, and that everything else we have to say to him this week does, too.

Stevie Wonder has millions (billions?) of fans the world over; you might already be one of them. But even if his music doesn’t mean as much to you as it does to me, or to our many other contributors, we hope that this package will get you thinking, talking, listening, and maybe even on the road to conversion. Most importantly, we hope it will convince everyone of the importance—particularly at the end of a year like this—of spending more time discussing and appreciating the lives of artists that bring us joy, whoever they are.