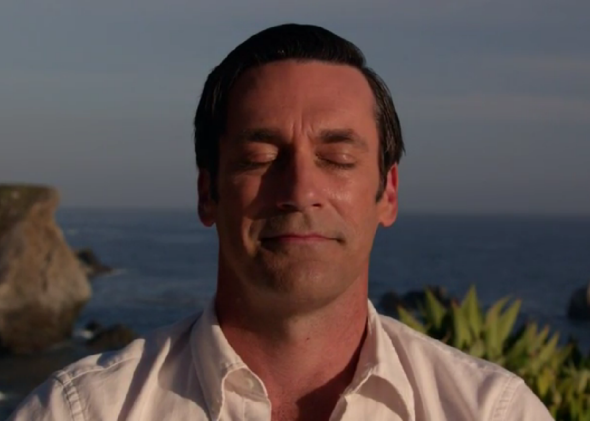

The Mad Men finale opens with Don gunning across the Bonneville salt flats, attempting a land-speed record for outracing the pain of his own life. By its close, though, our hero has achieved stillness. At a retreat full of hippies, he resists the suicidal lure of Big Sur’s big cliffs, rises at dawn, chants “om,” and smiles a Mona Lisa yogini smile. That’s the headline, folks: Don Draper finds peace at last! (A peace that will, it seems, eventually lead him back to advertising, McCann, and the creation of the “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” campaign that played before the credits—but peace nonetheless.)

The finale was kind to Don, and kind-hearted generally. Watching Matthew Weiner dole out so much redemption, hope, and love, after all his years convincing us that people are bitter, cruel and self-defeating, that they can never escape their own foibles and sins—well, it was what I said I wanted before the season began. In practice, it felt a little weird.

Why did Don stop running? There were two key moments in the episode that turned his world around, and both offered echoes of crucial scenes in Season 1. The first was a conversation with Anna Draper’s niece Stephanie. Stephanie gave her child to his grandparents to raise, and she tells the hippies at the retreat she feels like people are judging her for abandoning her son. Then the hippies start to judge her for abandoning her son. (“My mother left,” a woman in snug overalls says. “Your baby is going to spend the rest of his life staring at the door, waiting for you to walk in.”) When Don tries to console Stephanie afterward, he offers a version of the you-won’t-believe-how-much-this-never-happened speech he made to Peggy when she gave up her baby. Back then, Don argued for perpetual motion, for endless reinvention, and now he sings the same tune: “You can put this behind you,” he says, with the fervor of a lifelong escape artist. “It will get easier as you move forward.” “Oh Dick,” Stephanie returns. “I don’t think you’re right about that.”

After Stephanie leaves, presumably to engage her responsibilities in some way, Don goes dark at the thought of the responsibilities he’s shirked. The news of Betty’s cancer—and the fact that the one thing his first wife and daughter can agree on is that wherever Bobby and Eugene end up when she dies, it certainly won’t be with him—leaves him wrecked. He calls Peggy for an ominous goodbye/self-castigation session: “I broke all my vows. I scandalized my child. Took another man’s name. And made nothing of it.” For a moment it looks as though Don will end it all—there are no skyscrapers around, but those cliffs would do nicely—when a benevolent hippie nudges him toward a seminar.

There, a man named Leonard makes a speech about love that saves Don’s life. Ah, Leonard: Mad Men’s last great rando. God bless Matthew Weiner for squeezing one more in. Leonard, a bland office type, complains of feeling uninteresting, unseen, unloved. Of his family, he says: “They should love me. Maybe they do. But I don’t even know what it is. You spend your whole life thinking you’re not getting it, people aren’t giving it to you, then you realize, they’re trying, and you don’t even know what it is.” As the critic David Ehrlich pointed out in Slate earlier this past week, the question of whether Don believes in love has been central since the show’s pilot, when Don argued to Rachel Menken that love “doesn’t exist. What you call love was invented by guys like me, to sell nylons.” But Don has been looking for some version of love ever since, and he recognizes himself in Leonard’s dream about being on a shelf in a fridge, waiting to be chosen every time the door opens and the light comes on, bereft whenever it goes dark again. (Since this speech came a few moments after a distinctly un-Draper-worthy ad for Heinz’s new mustard, I couldn’t help but imagine Leonard and Don as matching condiments, side by side.) Don embraces Leonard, and sobs.

Why did Leonard’s tale move Don so? I think the milquetoastery of Leonard is crucial here. Don has long assumed that his dark past, his family, his sins, account for his vast hunger for love. But here’s an office drone in a V-neck who can articulate his precise emotional state with more power than Don has ever pulled off in a pitch. Understanding that his loneliness and lovelornness are universal is, somehow, just what Don needs. (This scene also so flagrantly violates Seinfeld’s “no hugging, no lessons” rule of television that it seems almost intentional.) Finally at peace, Don can stop running, return to New York, live his life, and make a few more ads—including one for Coke. (Someone buy Todd VanDerWerff a Coke for nailing that prediction.)

I liked Don’s feel-good arc, but I’m less certain about Peggy’s. The first rule of work husbands is “Don’t fall in love with your work husband.” Because Peggy and Stan have such extraordinary rapport, the scene between them was great fun—and it’s gratifying to see Peggy find personal happiness, not just professional success. But part of what was extraordinary about Peggy and Stan’s relationship was that it felt so office-true. Abiding love and support that’s not romantic; colleagues that become—the word Peggy repeatedly used when cajoling Don to return—a kind of “home”: These are aspects of office life that Mad Men has portrayed better than almost any other show. The amorous pairing of Peggy and Stan seemed to undercut that portrait. Still, I’ll probably rewind that scene and watch it again once I’m finished writing this piece.

Hanna, I’m dying to know what you made of the launch of Holloway-Harris, and the departure of Joan’s ornery hottie. And I know John Swansburg gets itchy every time Don enters the Golden State. How did Don’s sojourn among the hippies sit with you? What other aspects of the finale delighted you, or didn’t? For some reason I particularly loved Pete giving Peggy that cactus.

A lot has happened,

Julia