Hanna, Seth,

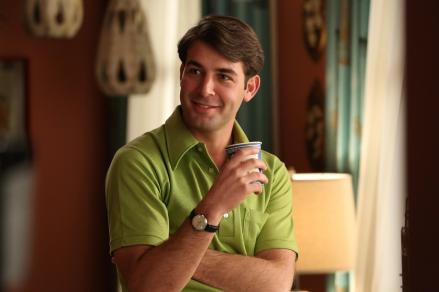

I am glad you asked me about Bob Benson. He came into focus for me this episode and I’m anxious to talk it out.

Bob has been the gun that might go off all season. People have put forth that he’s a spy or an investigative journalist, and now Ginsberg himself has asked if Benson is gay (shades of Salvatore Romano). This is television, after all, so anything is possible, including Bob realizing that he’s Don Draper’s long-lost gay son and killing the entire staff (except for Peggy, who is left to tell the story to Advertising Age). Or maybe, as has been suggested at Vulture and elsewhere, Bob is a doppelganger to Don. After all, he is inventing his own Bob Bensonhood in the same way that Don invented his Don Draperhood.

But perhaps a sort of “Weiner’s Razor” (ouch) applies. Maybe no great reveal awaits us, and when we peel back the Bob we’ll only be faced with yet more Bob. There was that brief scene in which Bob was listening to a sales seminar on LP, right before he got the call about Ginsberg. He didn’t know that particular call was coming; he just knew he’d need to pitch Manischewitz. Here’s what he heard, eyes closed, with an assist from a sales website.

Gentlemen, after all, this business of selling narrows down to one thing, just one thing: Seeing the people. Show me any man of ordinary ability [phone rings] who will go out and earnestly tell his story to four or five people every day, and I will show you a man who just can’t help making good.

That was Frank Bettger (who was in turn quoting an inspirational speech he had heard), from an album based on his best-selling How I Raised Myself From Failure to Success in Selling (1949). It turns out it’s a fairly well-known quote. And Benson, in a state of Bettger-inspired readiness, actually manages to inspire Ginsberg, enough to knock him out of his self-indulgent radical funk and back onto the bandwagon. Of course Ginsberg doesn’t really want out; he wants to act out. But he’s really good at advertising and probably not going to join the Krishnas a la Paul Kinsey or become a Hollywood player like Danny Siegel.

Benson, in the process of literally lifting Ginsberg from the floor, tells him to be ready. This state of alertness to opportunity is Benson’s capitalist version of Zen. It’s too soon for est and the Landmark Forum. But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t already established a grand tradition of opportunity in American business, albeit one that hardly ever gets discussed in highbrow media. Maybe it’s because TV writers are naturally horrified by stuff like Who Moved My Cheese? (True, the film version isn’t great.) But literary merit aside, business fables and stories of success have been part of the American narrative since Ben Franklin.

Since the country was founded, if you wanted to pull yourself up by your own bootstraps, there was always someone ready to sell you the bootstraps. For example, starting in the early part of the 1900s you could send away for a full set of Alexander Hamilton Institute “Modern Business” volumes. Small, pocket-sized books to teach you all aspects of business. They show you how to plan a factory floor and do the books and write advertising, too. I own a copy of the whole set and I love leafing through them.

Of course there’s Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Before that, in the 1920s, there was The Man Nobody Knows, about how Jesus was the first great businessman. (“The second [secret of Jesus’ success] was his wonderful power to pick men, and to recognize hidden capacities in them.”)

But ranking right below Franklin in importance to business lore is Elbert Hubbard’s 1899 “A Message to Garcia,” which sold 40 million copies and which I urge you to read. It will make you want to go out and do some business, right now. It’s about a man, Rowan, who was given a letter by President William McKinley for Calixto Garcia, a leader of the Cuban rebels. So “Rowan took the letter and did not ask, ‘Where is he at?’ By the Eternal! there is a man whose form should be cast in deathless bronze and the statue placed in every college of the land.” It only heats up from there. Here’s a taste:

We have recently been hearing much maudlin sympathy expressed for the “downtrodden denizens of the sweat-shop” and the “homeless wanderer searching for honest employment,” and with it all often go many hard words for the men in power.

Nothing is said about the employer who grows old before his time in a vain attempt to get frowsy ne’er-do-wells to do intelligent work; and his long, patient striving with “help” that does nothing but loaf when his back is turned. In every store and factory there is a constant weeding-out process going on. The employer is continually sending away “help” that have shown their incapacity to further the interests of the business, and others are being taken on.

Bob Benson is ready to take a message to Garcia. Benson has always been ready, every time we’ve seen him. He wants a place for himself as a first-class citizen at SC&P. And Bob, praise him, doesn’t ask for slack. He’s willing to earn that place, if he could just get a chance.

Advertising is a weird industry because it throws people like Jim Cutler and Michael Ginsberg into the same office. You need Jim or Roger to smooth things with clients, to impress them with pedigree and promise them access to a world of pleasure and excitement, and, if they buy a campaign, material success. But Ginsberg, Stan, and Peggy are the engines that push things forward. Even if they call you a fascist, you need them.

So Cutler listens to Ted Chaough’s reasonable defense of Ginsberg, and that sets in motion a series of events that lead to Benson getting a chance to shine at a client meeting, taking over a task that Roger had deferred to Jim. Cutler sees in Bob a man who will take the message to Garcia. That he fails doesn’t really matter; it was thirdhand work anyway, and not Jim’s client. The key thing is that he showed up to do it.

Contrast that with Pete being told he’s head of new business. “Since when?” he says. “I don’t want that!” Perhaps Bob is an analog to Don, or perhaps Bob is the anti-Pete. Bob is exactly what you’d want your employee to be: eager, ambitious, relentlessly positive, grateful to help. That he lacks any obvious inner life aside from inspirational seminar thinking, is almost a benefit. Nothing to bog him down.

My bet is that the joke is on us, that there is no great reveal. Bob Benson is a way for the writers to show us how, in the world of Mad Men, the very qualities that define a real go-getting American businessman, here, in this office, with these people, look like vile perversion. To propose that Bob Benson is a spy is, frankly, to dance on Dutch Reagan’s grave. If you suspect Bob, you suspect the backbone of American commerce. If you suspect Bob, you suspect opportunity itself.

What I want to see is what happens when his ethics are really tested, when he is forced to choose sides. That the entirety of the renamed SC&P is headed to a showdown that pits the ex-SCDP team against the ex-CGC team means that we could see what happens when an ideology of pure sales success smashes into the realpolitik of intra-agency warfare. This episode—that brief scene with the record player and Frank Bettger in his ears—has made me hopeful that we will see exactly that.

You gotta be in the right place all the time,

Paul