In Slate’s Arrested Development TV Club, two fans will IM about each episode of Season 4 once they finish watching it. Today, copy editor Lowen Liu and television critic Troy Patterson recap Episode 12, “Señoritis.”

Lowen Liu: Troy, your 2006 review of the original AD finale closed on Maeby meeting with Ron Howard to pitch her family’s story, which becomes a central plotline this season—but for Michael. Come on! In the way you lamented the end of the show having “turned itself inside out” with its gags, you presaged what is fatally flawed both about this season and about poor, unloved Maeby. The youngest Fünke has always managed to be the most canny and yet the most trapped, and this episode shows her in an endless cycle of con after con, all in the sad attempt to get her parents’ attention. It’s an emotional Ponzi scheme that reminds me of the show itself. What say you?

Troy Patterson: Please tell me more about this 2006 review! I haven’t read it since I wrote it, but it is my recollection that I declared the final episode of that third season to be a bit wearying in its navel-gazing—a bottomless belly button of inside baseball. I remember thinking that the original finale was more clever than it was funny, and the episode under discussion today reduces that earlier absurdist excess to its absurd essence.

Liu: If “Señoritis” is the concentrated reduction of all of AD, Maeby is the purest expression of Bluthness. Irredeemably damaged by selfish parenting, cunning, manipulative—and remorseless. “Aw, no, I’m fine,” she says after dipping her toes in guilt and finding it too hot. Her explosive rant at the Opie Awards (how did the “cunt-punt” lines get in there so quickly, just weeks after their sorority source hit the air waves?) was the kind of catharsis that withers in every other Bluth before reaching expression. I have rarely felt so satisfied for and sorry for a character of farce.

Patterson: That was a memorably bitter expression of hatred for show biz, and I’m not sure what to make of the tantrum being placed among an uncountable bevy of self-reflective references to Ron Howard and Imagine Entertainment, the company he founded with Brian Grazer. At this point, the show’s creators are on one level mocking the insider quality of their inside jokes—or so it seems when Maeby’s firing from Imagine is minutely detailed by Deadline Hollywood (the trade-mag website that may or may not still be run by the singular Nikki Finke). Maeby is dismissed after it comes to light that she does not have a high school diploma, having followed through on a plan to stay in high school until her parents notice her. Now she’s a permanent 12th-grader, and I wonder: Arrested Development, the title itself, is rich with punning meanings. Is it legit to interpret the phrase also as a comment on Maeby’s progress through life?

Liu: By that reasoning, Mitch Hurwitz must have dropped to his knees in gratitude when AD was originally canceled. The show’s own development, arrested! It must have felt like the ultimate permission slip to do as he liked, the labyrinth’s Minotaur given his own hammer and nail. Everyone has suggested that the 30-odd-minute running length and the actors’ scheduling restraints are to blame, but maybe the problem actually goes back to 2006, and that the fateful meeting at Fox HQ was more or less Hurwitz’s own Queen Mary becoming unmoored.

Patterson: The contempt for self and others is really quite astounding. I found myself wondering if Maeby’s incompetence at arithmetic was a nod to “Hollywood math”—the accounting institution that enables studios to screw people over by insisting that net profits never exist. I also want to connect Maeby’s educational status to the old truism that Hollywood is like high school with money. And speaking of status: I want to link Maeby’s search of self-esteem with this series’ existence as something of a Howard–Grazer vanity project. Hurwitz is the author, yes, but the producers behind this avant-garde farce are investing in their social capital.

Liu: That’s true. I sense we were expected to be tickled much more than we were by Howard’s omnipresence in this season, voice and face both. Earlier you had some hopes for this season’s challenging our notions of what a sitcom is. Do you have a better idea now, nearly on the other side? I laughed less over this whole season than in nearly any randomly chosen 20-minute block from 2005 AD. Now I’m wondering if that was on purpose. The show’s ruthlessness here, about money, marriage, family, put me in the mind of—this is an odd connection, but humor me—Samuel Butler’s classic novel The Way of All Flesh, a vicious repudiation of Victorianism cloaked in light barbs and cheeky maxims. Perhaps we’re at a similar point in history now. I’m affected, perhaps, because Maeby is the third generation, as the hero of that novel is. She is the one who is supposed to get away. And yet at the end she is placed in handcuffs and dragged back, in legal status and eventual geography (is there a more ominously named housing project than Sudden Valley?), to precisely where the rest of her family is. I’m starting to suspect we’re headed toward a Seinfeld ending, everyone in jail.

Patterson: Do I have a better idea of what this intriguing monstrosity is accomplishing? No—but I remain captivated by the virtuosity of its storytelling. Correct me if I’m wrong, but the intricacy of its chronology is without precedent in the history of narrative. One legacy of this fourth season is that comedy nerds of the future, looking back on the puzzles of it, will all have to learn to talk smartly about fabula and syuzhet. Also, the ostrich never fails to crack me up.

Courtesy of Netflix

Liu: I was never patient enough to solve jigsaw puzzles as a kid. Similarly, I had fun here seeing Barry the attorney trying to break into the high school while dispensing pro bono advice to Maeby (a freebie, if you will), and can somewhat piece it together with the O.J.–like scene of him at the same gates in another episode, but I fear I’ll have to dip into Reddit-based chronological recuts to really find out what’s going on there. I don’t want to have to pause and get out a magnifying glass to try to figure out exactly what was on the other half of George Michael’s flag pin.

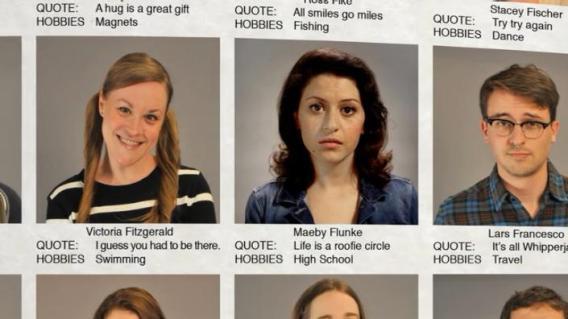

Patterson: I hear you. The pause button and I spent quite a few minutes studying the folios of Maeby’s many yearbooks. It was not time well spent. I guess it was slightly cute that one of her activities was the Friars Club.

Liu: I’m also not sure quite what to make of FakeBlock, the anti-social network, and what George Michael’s startup says about the fatigue we may or may not be feeling in this connected day and age. What is Hurwitz and Howard’s latest incarnation of this product if not a social network itself, and a text which if not read communally is not read at all?

—