Is Othello black? With the news that David Oyelowo will play Othello opposite Daniel Craig’s Iago and that the Metropolitan Opera is finally discontinuing the practice of blackface in productions of Otello, we may see a revival of this oft-asked question. What people mean when they ask if Othello is black is: What did Shakespeare mean when he called Othello black? Would we say Othello is black today?

It’s an understandable question. Shakespeare’s writing mostly predates the transatlantic slave trade and the more modern obsession with biological classification, both of which gave rise to our contemporary ideas of race. When Shakespeare used the word “black” he was not exactly describing a race the way we would. He meant instead someone with darker skin than an Englishman at a time when Englishmen were very, very pale. Although Othello is a Moor, and although we often assume he is from Africa, he never names his birthplace in the play. In Shakespeare’s time, Moors could be from Africa, but they could also be from the Middle East, or even Spain.

Photo courtesy Library of Congress

While the question is logical to me, as a reader, a director, and a lover of Shakespeare, it’s not the most interesting one. As language’s meaning evolves, so do these plays, even if their words remain exactly the same. To us today, the word “black” carries with it a specific cluster of associations informed by history, culture, stereotypes, and literature. Othello may have started in conversation with Shakespeare’s definition of blackness, but today, he speaks with ours.

A much more interesting question, really, is: Why is Othello black? Why did Shakespeare write a domestic tragedy about jealousy, and make the husband a Moor? Is Othello’s race a canard, or is it the key to unlocking the play’s deeper meanings?

Would you believe the answer to all of this might involve pirates?

Before we hoist the Jolly Roger, we should consider more practical explanations for Shakespeare’s choice. In August of 1600, the ambassador of the King of Barbary—roughly, modern-day Morocco—came to London as the guest of Queen Elizabeth for a six-month residency at court. He was a celebrity, Katie Sisneros, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Minnesota focusing on representations of Turks in English popular literature, told me in an interview. “He would’ve had some sort of public parade. People who had never seen a Muslim, never seen a Moor, they probably saw their first Moor during that visit.” Something of the ambassador’s charisma and dashing good looks remain in this portrait of him painted in England at the time.

We know from records that Shakespeare’s company performed at court while the ambassador—his full name was Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun—was there, which means that Shakespeare may very well have acted in a play in front of him. (Of course it’s just as likely that one or both men had a cold and missed the show; that’s how nebulous Shakespeare scholarship can get.) Shakespeare likely began writing Othello the next year, and performed it for the first time in 1604.

If we remember that Shakespeare was a human being and a good businessman, we get the most obvious answer to our question. The Bard had just met and performed for a Moor who was a superstar. England’s relationship to the Ottoman Empire and to Moors was a pressing issue. Moors were so hot right now back then. From there, we can imagine our inspired playwright casting about for a story about a Moor—Shakespeare’s plots were mostly unoriginal and adapted—and finding Giraldi Cinthio’s Hecatommithi, a short story collection modeled on the Decameron. Shakespeare takes two cups of Cinthio, mixes a few dashes of purloined “facts” about both Africa and Venice from recently translated books and, in a couple of years, he’s baked a play.

Unfortunately for Shakespeare, in between Abd Anoun’s visit and Othello’s premiere, Queen Elizabeth died. King James had a much frostier relationship with the Ottomans than his predecessor did. “James tried to roll back the diplomatic advances that Elizabeth made,” Sisneros said. “He starts using ‘let’s have a new crusade’ language.”

Painting by William Mulready/Walters Art Museum

Sisneros told me that to much of Shakespeare’s audience, “all Moors were Turks, even though not all Turks were Moors.” Furthermore, while calling someone a Moor meant that they had dark skin, in the early 17th century, the term carried a religious meaning as well. “There was no word for Muslim at the time. They used Turk, Mosselman, Mohammedan, these are all synonyms.”

Othello, then, may have appeared at the time as an ex-Muslim—he mentions his baptism within the play—who slowly reverts to behavior that is more stereotypically “Muslim.” The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice could be read as a nightmare about the impossibility of conversion and assimilation, meanings within the play that are less visible to us because we lack the original audience’s context.

This is where piracy becomes important. If you were a British sailor working a trading ship at the time, you ran a real risk of being sacked by pirates, often Turks. If this happened, you were ransomed or, if no ransom was forthcoming, enslaved. Often, you would be offered your freedom if you converted to Islam, a process called turning Turk. To sweeten the deal, you could be promised land, a job, or even a wife. “If an English person is kidnapped, sold into slavery, converts for their freedom, returns to England—and this happened a lot—could they convert back?” asked Sisneros. “And if so, how could that conversion be trusted? It’s an extremely troubling question at the time.” Othello even uses this anxiety when breaking up a fight between his men, asking them, “Are we turned Turks? And to ourselves do that/ Which heaven hath forbid the Ottomites?”

Similarly, many English feared that Muslim converts to Christianity were incapable of fully changing. Othello’s blackness, then, worked for the play’s original audience as a symbol of his “true” essence. Iago scrapes away the veneer of manners Othello has layered over this, revealing what Shakespeare’s audience would’ve thought was “real” all along. In the second half of the play, Othello begins having seizures and wild mood swings, and his vocabulary gets simpler. Othello himself echoes the idea that he’s “reverting” when he commits suicide, describing to the assembled Venetians how he wants to be remembered:

And say besides that in Aleppo once,

Where a malignant and a turbaned Turk

Beat a Venetian and traduced the state,

I took by th’ throat the circumsized dog

And smote him—thus! Stabs Himself

Othello could be talking about Desdemona as the abused Venetian or, according to Sisneros, “he could be even referring to himself. He killed the good part of himself, thus ‘traducing’ the Venetian state.” Either way, it’s hard to escape the sense that Othello is explicitly saying he has “turned Turk” by the end of the play.

It could also be that Othello’s blackness provided Shakespeare a new way to explore questions that consumed his playwriting at this time in his career: What is identity, and how is it formed? What is a man? What is an Englishman?

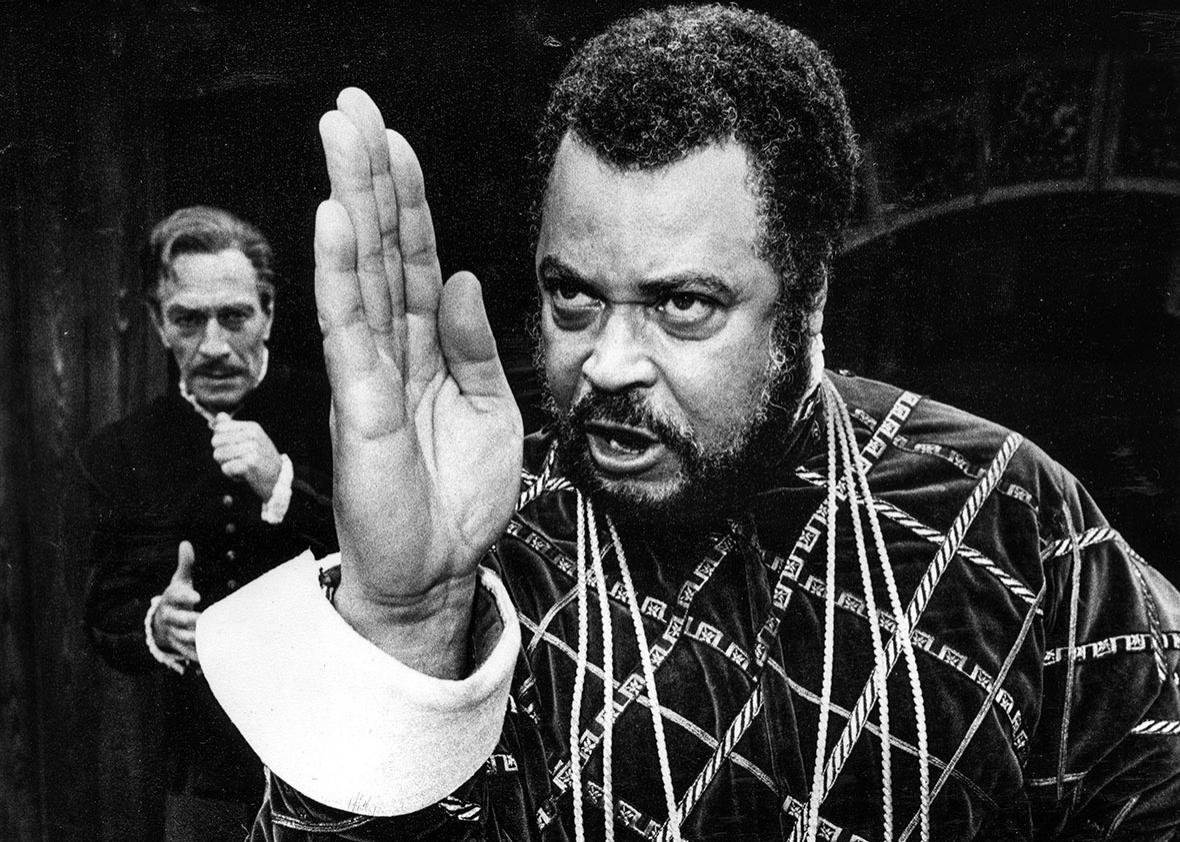

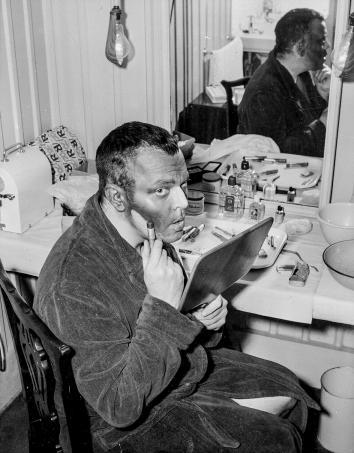

Photo courtesy Dictionary of Theatre/Public Domain

To understand how Othello helped Shakespeare tease out those questions, let’s first look at how Shakespeare used references to blackness. There are many (largely negative) uses of the word “black” throughout the play, and there are ways that characters reference Othello’s blackness without using the word. Brabantio, Desdemona’s father, enraged at his daughter’s elopement, accuses Othello, saying, “Damned as thou art, thou hast enchanted her,” because she never would’ve consented to run “to the sooty bosom/ of such a thing as thou.” “Sooty” refers to Othello’s skin color but, importantly, “damned” does too. Devils in Shakespeare’s time were thought to be black. Black skin was a sign of being a devil, capable of witchcraft. Later, Iago promises to turn Desdemona’s reputation as black as “pitch.”

Complexion in Shakespeare’s time was a measurement of both beauty and virtue. According to Villanova Shakespeare scholar John-Paul Spiro, to be “fair” was to be both pale and virtuous, not synonymously, but simultaneously. Similarly, Spiro said, “if you look at the poetry, Black-means-ugly is all over the place. The Dark Lady in the sonnets, for example. Shakespeare can’t stop pointing out that she’s not supposed to be attractive because she’s ‘dark.’ In Much Ado About Nothing, Claudio says he’ll marry a woman he’s never met ‘tho she be an Ethiope,’ a word Shakespeare uses in other plays to mean both black and ugly.” Shakespeare was a product of his time, after all, and in his time men were publishing texts like Stephen Batman’s The Doome Warning All Men to Judgement, which describes “Ethiopes” as having “four eyes: and it is said that in Eripia be found” men that “are long necked, and mouthed as a crane.”

Photo by L. Waldorf/Getty Images

Othello only uses the word “black” to describe himself twice. Once, as he contemplates Desdemona’s infidelity, he says that perhaps she has strayed because “I am black/ And have not those soft parts of conversation/ That chamberers have.” Later, he says that if she’s cheated on him, “Her name, that was as fresh/ As Dian’s visage, is now begrimed and black/ As mine own face.” His otherness, the “passing strange” aspects that made him alluring to Desdemona, have now become ugly in his eyes—because he believes they’ve become ugly in hers. His entire conception of who he is has changed, paving the way for the murder of his new bride.

So does Othello treat Othello as a monster or do the characters in Othello make him that way? To Spiro, the unanswerability of the question is what makes it worth asking. “At this time—remember he’s written Hamlet, Twelfth Night, and Measure for Measure not too long ago—Shakespeare is preoccupied with and invested in a deep skepticism about the knowability of the world, the self, and the other. You are a mystery to yourself; other people are a mystery to you. What is terrifying about Othello is that the mystery deepens with intimacy.”

Spiro traces this thread in Shakespeare’s writing to the Bard’s likely familiarity with Montaigne’s Essays, which often double back on their own assumptions, and with the shifting theological emphasis of Protestantism. “In Catholicism, to be a good person, you have to go to confession and mass. Protestantism is now saying ‘No, you must always doubt your intentions, you must always wonder if you did things for the right reason.’ ” As a result, Shakespeare’s characters’ thoughts become a swirling vortex of uncertainty. “Look at Brutus,” Spiro said. “Look at Hamlet. The more you interrogate the self, the more incoherent and unknowable it gets.”

Photo by Castle Rock Entertainment via Getty Images

And Othello presented Shakespeare’s audience with a kind of incoherence when he first walked onstage: He did not fit any of his era’s stereotypes of how he should behave. At the beginning of the play, Othello is straightforward, honest, and noble. He cannot conceive of being lied to. He isn’t at all what an English audience would expect. The Venetians around him, on the other hand, are exactly what the audience would expect. They’re, venal, dishonest, passionate, and unfaithful. Iago’s case against Desdemona rests in part on using these stereotypes as proof. As he says to Othello, “In Venice [wives] do let heaven see the pranks/ They dare not show their husbands.”

“If Othello really is that decent, honest, and credulous, if he can really have friends and be loved by a beautiful woman, the white characters in the play can’t accept it,” Spiro said. “Iago has to destroy him.”

Throughout his career, Shakespeare was conflicted about identity at the moment when the question What is an Englishman? was as vital to his audience as questions about identity are to us today. “In Twelfth Night you have the idea that you could make someone insane simply by telling him he’s insane,” Spiro said. “If Richard III had had a straight back, would he be a good person? Is his crooked back a sign that he is a bad person, or do we treat people with crooked backs badly?” To Spiro, the terrifying note Shakespeare sounds again and again, despite being a word-drunk pioneer of the English language, is that talking about it doesn’t help. Hamlet can’t reason his way out of the trap of the self. Neither can Othello, who is helped neither by logic, nor by proof, nor friendship, nor even by language, because all of these normal ways of making sense of the world have been arrayed in a conspiracy against him by Iago.

All along, the play is asking what makes a person, what is identity, and how belonging to an identity group shapes who you are. These questions haunt us today, but they were important to Shakespeare’s audience as well. Moors weren’t the only converts, after all. The entire nation had recently “converted” to the Church of England. If, according to your new faith your goodness is never guaranteed, and if all Iago needs is two days to turn a noble convert and trusted military leader into a monster, imagine what he could do if left alone with you.