Dear clubbers,

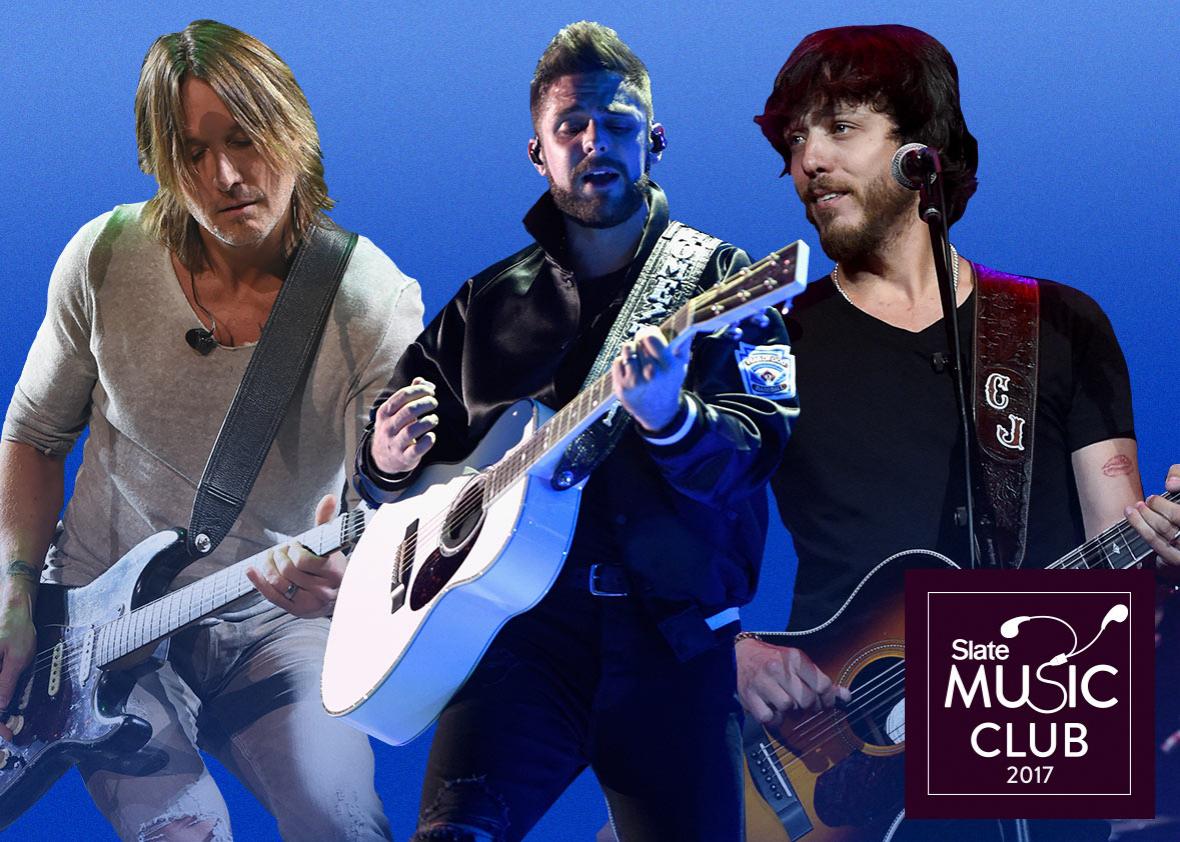

I imagined, Jewly, that you were going to bring up chart country’s shift this year from bro country toward beau country or, as Jon Caramanica put it in the New York Times, the rise of the “country gentleman.” I hadn’t considered it as a response to the political climate, as you suggest. It makes sense as one that, while not exactly liberal much of the time, is seeking conciliatory, humane alternatives to overheated culture-war polemics. Many of these songs seem like successors to last year’s Tim McGraw hit, “Humble and Kind” (written by the excellent Lori McKenna). But I do begin to wonder how much pious moral instruction country listeners can take. In Thomas Rhett’s catalog, “Marry Me” is a welcome exception to all his supersincere tributes to his own wife—among them, I like “Life Changes” because it’s so meta, referring explicitly to the recent events of his own music career, like a “Ballad of John and Yoko” without the paranoia. And Rhett is the kind of singer who can make even semimediocre material glow. On the other hand, OK, OK, Thomas, you like your wife, we get it.

And yes, Jewly, when pining for more respectful treatment of women on the country charts throughout the “bro” years, I’m not sure anyone was asking for songs like “Drunk Girl” and “Female,” which take it to the point of caricature and end up condescending in every direction, like gender-politics versions of the notorious “Accidental Racist.” Be careful what you wish for, I guess. Except that what we were really wishing for was that radio and the charts would actually make room for all the great women in country we’ve been mentioning here (Margo Price, Cam, Kelsea Ballerini, Angaleena Presley, Brandi Carlile, Ashley McBryde, et al.), who can more than speak for themselves. And that still hasn’t happened much, even with this year’s comeback from Shania Twain, that core avatar of country “girl power.” (Her album’s been overlooked in year-end lists, but it’s fascinating for how it adjusts her style to her diminished vocal strength and to contemporary production.) Instead, we’re getting offered new variations in masculinity: You can have any kind of country music you want, as long as it’s by a man.

Country’s always gotten its ideas across better with storytelling than with virtue signaling (a term that applies here if it does anywhere). One new country dude with a raconteur’s touch I’ve been enjoying is Luke Combs. His hit “Hurricane” tells a commonplace tale (an on-again-off-again turns back on) in an unusually vivid way, and “When It Rains It Pours” turns a sour-grapes breakup song into a comical romp (too bad about the annoying mother-in-law joke). Then there’s Charlie Worsham and Walker Hayes, both of whom Jewly mentioned. I’m not taken with the way Hayes’ hit “You Broke Up With Me” thumbs its nose at the ex it’s addressing. But I love “Shut Up Kenny.” It’s a song about souring on your favorite music when it reminds you too much of the one who got away. But its compliments-disguised-as-burns for Kenny Chesney (“Shut up, Kenny, keep your songs to yourself/ Why you gotta sound just like she felt/ When your stuff was the shit we drove around to/ And even your sad songs were fun to make out to”) make it the cleverest tribute from a newer Nashville voice to an established one since a young Taylor Swift sang, “When you think Tim McGraw, I hope you think of me.”

We can’t talk about the year in country, though, without mentioning the Route 91 Harvest festival in Las Vegas, where country fans became the targets of the largest mass shooting in modern American history. More than two months later, why it happened remains a mystery, except for the usual part, which is that American law still lets people assemble military-scale arsenals to carry out such schemes. While many Nashville stars have done conscientious work on behalf of the victims, we still had the Country Music Association trying to ban mention of the events and related political issues at its awards show in November. The association backed off, but it helped make me appreciate one particular country song, “Thoughts and Prayers” by Will Hoge, for calling out the rote bullshit responses and pointing squarely at the unholy union between politicians and the NRA, which extends in many ways to the country-music industry, too.

Now, from the horrifying to the just plain sad: It didn’t feel quite as flattening as 2016, but this year saw a lot of goodbyes to musicians, too, from rock ’n’ roll pioneers like Chuck Berry and Fats Domino to stalwart figures such as Tom Petty, Gregg Allman (as well as Butch Trucks, also of the Allman Brothers Band), Glen Campbell, Steely Dan’s Walter Becker, Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell, and Grant Hart of Hüsker Dü (well memorialized with the new early-works compilation Savage Young Dü) to—as we’ve already discussed—Prodigy of Mobb Deep and the young rapper/singer Lil Peep.

As was expected, we also lost Gord Downie of the Tragically Hip, an obscure name to most Americans but huge among my fellow Canadians. He was a charismatically eccentric frontman who blended bar-band rock with singular poetry and a keen awareness of history, geography, and social justice. Even while suffering from incurable brain cancer, Downie was making words, music, and alliances in the cause of Canada’s reconciliation with indigenous people—and reaching middle-class, white constituencies that often hadn’t engaged with those issues before.

And that list is far from complete. One of the saddest deaths this year, for instance, was Jessi Zazu of the terrific Nashville alt-country band Those Darlins, who died of cervical cancer at only 28. And just this week, there’s Kim Jong-hyun of the massive K-Pop band Shinee, who died at 27, having seemingly killed himself—will his passing stir any demands for reform of the regimented, pressure-cooker conditions of the Korean pop industry?

Also this month, while we’ve been chatting, we lost the great free-jazz drummer Sunny Murray (who backed up Albert Ayler and Cecil Taylor on crucial recordings), as well as Ralph Carney—a sax player but also on toys and invented instruments, who with his band Tin Huey came out of the same experimental proto-punk Ohio scene as Devo and Pere Ubu. He moved on to the Bay Area and performed and recorded with countless musicians, most prominently Tom Waits, as well as his nephew Patrick’s band, the Black Keys. This decade, the two of them composed the memorable theme for Netflix’s great animated series BoJack Horseman. Carney was an irrepressibly creative spirit, really one of a kind.

These departures are always heartbreaking. But they’re also opportunities to recall, learn, and talk about parts of cultural history we might otherwise neglect. For instance, I’d always taken Tom Petty for granted—I liked the songs, of course (I’m not a monster), but I’d never dug in very deep. His death prompted me to watch the documentary Runnin’ Down a Dream, a four-hour epic directed by Peter Bogdanovich. It illuminated Petty’s roots and connections in Southern rock and Southern culture in ways I hadn’t considered, along with his complex battles with music-industry practices (he sang “I Won’t Back Down” for a reason), among other subjects.

But that is just one example. The death of French rocker Johnny Hallyday, for instance, could become your window into the ways Elvis inspired new hybrid expressions all over the world, including in cultures where rock ’n’ roll was kind of an awkward fit.

In a similar spirit, I’ll close this post by sharing with you one of the most tragic music stories I read this year, from Ann’s colleagues at NPR Music. It’s about Fred “Freak” Smith, one of the handful of high-profile black American musicians on the 1980s D.C. hardcore punk scene, best known as a member of Beefeater. His body was found this summer in Los Angeles, stabbed, after many bouts of addictions and homelessness. He was in his mid-50s. But Andy Hermann (former music editor of L.A. Weekly, another institution that requires mourning) really captures the complexities of Smith’s life and death, and the way that his former friends back in D.C. are wrestling with whether they could have done more for him. He includes a quote from the ever-eloquent Ian MacKaye (of Dischord Records and Fugazi) that I think will ring true to anyone who’s participated in a close-knit music scene, or any kind of independent cultural community.

“I think people who feel marginalized or feel freaky or don’t fit in, there was a period of time where the extended family we created within our scene was a safe haven for them, and they flourished,” MacKaye said. “And then, as all things do, it fell out. But I like to think it was a respite.”

Sometimes, perhaps, that’s the best we can ask of our few moments together.

Why is it so hard to accept the party is over?

Carl