Hola, Carl and Ann and everybody! The kinder, gentler, cozier, less homicidal Winter White House. It’s good to be back.

As you note, Carl, this year seemed like the longest since the dawn of humankind, and the past few months have been nearly impossible, as we wade through the unending river of trash wrought by powerful (mostly) men. #MeToo has conjured a collective trauma more urgently and painfully than an entire year of the (alleged) Assaulter in Chief bringing the whole world to the brink, and personally it’s moved me to wrap myself in a cocoon of music by self-determined women who’ve reimagined the parameters of what a “diva” can be.

You rightly point out that the big pop empowerment anthem is dated and of another era (if I ever hear “Fight Song” again in this lifetime, I might have to). Less than a relic of the Obama years, though, it’s very specifically tethered to the loss of Hillary Clinton, who seemed to embody every tenet that those songs were dead set on convincing us—you can do anything!—and rehashing them felt about as worth our time as relitigating the election on Twitter. But these types of tracks have merely shifted, concurrent with the slumping slurs of the Soundcloud-rap teens, supplanted by the more microscopically personal meditations on love and agency—the general replaced by the hyperspecifically individual, as embodied by sublime albums by SZA, Kelela, MUNA, and Lorde. I saw this not as a dissipation but a necessary shift that reflected the heavy soul-searching into which we collectively plunged; in a year when many of our identities were being attacked, some of the best music doubled down on asserting its individuality. The personal was more political than ever.

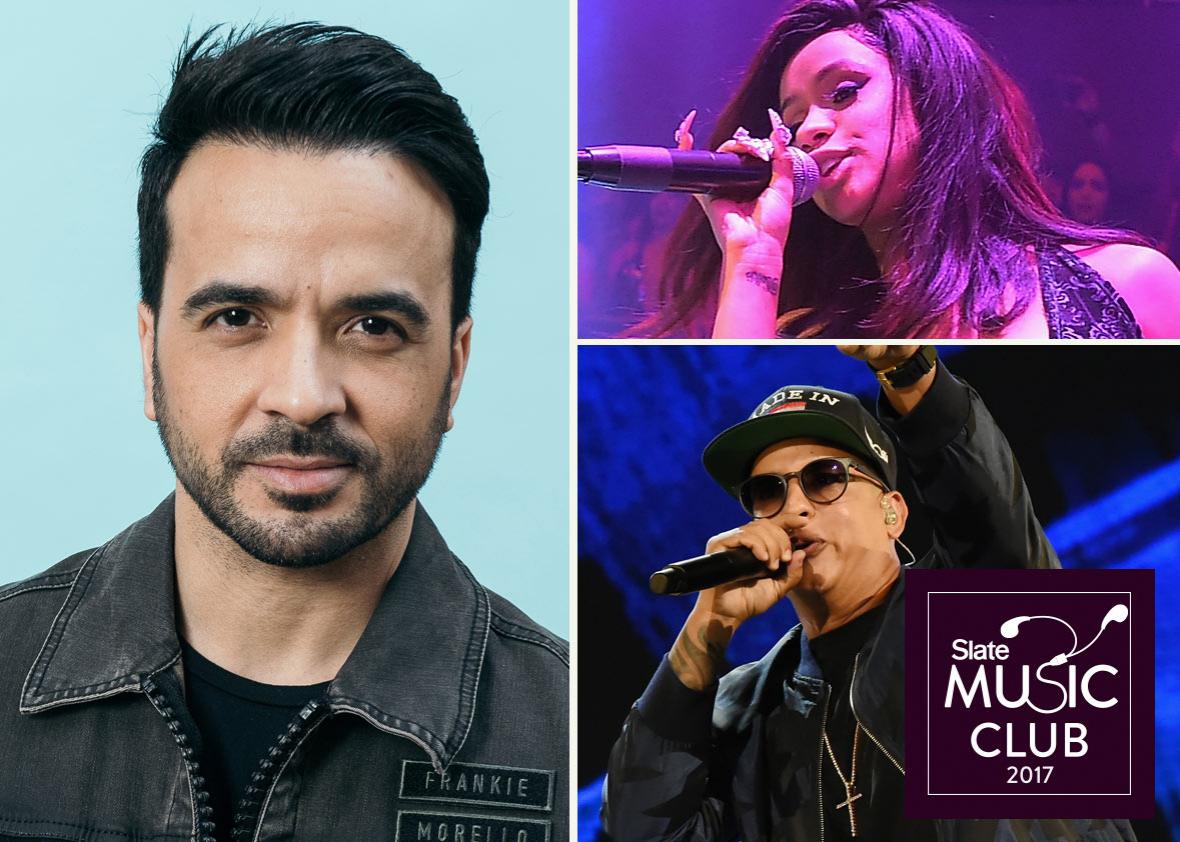

Which brings us to 2017’s other huge story: the pop-chart rise of “Despacito” and all the Spanish-language remixes it brought along with it. Pop’s hankering for emotional quasi-dembow (Drake, Biebs, Ed Sheeran) didn’t hurt it, but this track’s ascent was one of the more hopeful musical stories of the year, at least for those of us who’ve long groused at the way Latin music is segregated and marginalized by the music industry and all its vagaries based purely on language barrier, with disregard for the growing U.S. demographic who listens to it. Bieber’s disrespectful ass might have assisted “Despacito” in exploding, but make no mistake, Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee are powerful; that the remix tipped over into the pop charts after dominating the global Latin charts for weeks seemed inevitable. (Put empirically: In San Juan in July, when “Despacito” was just hitting its peak in the U.S. and bumping from seemingly every Brooklyn car stereo, I heard it in the wild a total of two times and not once at the club where the video was filmed. It was already old news.) And while a devastated Puerto Rico sat despicably unaided for weeks after Hurricane Maria, Beyoncé hopped on another wildly popular (in the Latin world) track, J Balvin’s “Mi Gente,” as a fundraiser, pushing the reggaetón-lite sound even further into the English-speaking mainstream. And as Latin trap reached its own pinnacle this year, English-language rappers wanted in on the action—Nicki Minaj and 21 Savage hitting up “Krippy Kush,” by boricuas Farruko and Bad Bunny and Jamaican producer Rvssian, was more evidence that audiences’ openness to Spanish-language music is widening (and perhaps concurrent with the inevitable “browning of America”—we coming for you).

So Cardi B’s overall memeability was central to her success, but even deeper was the way she represents American millennials in a shifting and viciously maligned demographic—a formerly struggling Bronx-born child of immigrants, an Afro-Latina, a bilingual hustler who embodies the multiplicity of her Trinidadian and Dominican cultures (see: “Bodak Amarillo”) and an outspoken advocate for young women in domestic-violence situations. (The American bootstraps narrative is a destructive myth, but if that’s what these people want, then here you go.) Nothing made me happier than seeing “Bodak Yellow” become an unofficial national anthem, its toughness and rap-along quotient serving as a kind of catharsis for millions of people whose only recourse, seemingly, was air boxing and screaming “IF I SEE YOU AND I DON’T SPEAK, THAT MEANS I DON’T FUCK WITH YOU.” The joy within!

As to your last question, Carl—about the encroaching influence of Spotify’s scrubbed-clean, impersonal, vaguely demonic algorithms—it’s of a piece with the larger issue we’re facing with mass deregulation and opaqueness in corporate structure, and it’s bad for us all. I am fairly agnostic about format, as someone who spent my formative years as a music critic buying import 12-inch singles and rap mixtapes (in CD form!) from shady stalls on Canal Street, but the flattening of taste via cold math and shadowy playlist makers is, for the listener, fundamentally a question about freedom of choice. Is the ease and convenience of having every song at your fingertips (or the appearance of such) worth it? It seems it leaves us with less to work with and does a Black Mirror number on our individuality. Ann, where’s your paranoia level on this? Mine is dystopian, but then isn’t everything.

Siempre estoy depositando, tan cansao de mí en el banco,

Julianne