Hey Slate Music Clubbers,

Glad to be back in conversation with you, as always. You feel like home to me.

There’s a one-story building right next door to the downtown Manhattan apartment I’ve called home for more than a decade, and it’s been scheduled for demolition for several years. A shiny new high rise is supposed to take its place, and it threatens to forever block my sunny views in exchange for years of construction-generated dust, ash, and noise that will make daily living something of a nightmare for me. I live in a posh neighborhood, so this may be no more than a Champagne problem. But it still feels like my home, my living sanctuary, is imperiled. Demolition started this summer: I’ve been peering out of the window every day to watch construction workers sporting asbestos-protecting hazmat suits jackhammer steel beams and turn concrete into rubble. But the destruction—hopefully not toxic for my health and that of my neighbors—is excruciatingly slow with no definitive end date in sight. Watching things fall apart in slo-mo and get torn to shreds outside my window on a daily basis has left me in a yearlong state of prolonged dread and nerve-wracking uncertainty.

I’ve been thinking of that impending calamity next door as a metaphor for what we’ve all been writing about as a terrible year—a year that could, in turn, signal an imminently catastrophic future. We’ve all been reminded that things don’t necessarily get better—they could just as easily fall apart in light of the tectonic shift that was the U.S. election and similar referendums in Britain, Colombia, and Italy as well as burgeoning right-wing populist movements in Germany, France, and Austria (to name a few). All this socio-political upheaval unfolded in the midst of mass-mediated smoke bombs of disinformation and fake news that has left many of us sometimes unable to properly parse out the difference between what’s real and what’s not.

Calamity this year tasted like toxic water in Flint, Michigan; it felt like the rumble of the deadly Italian earthquake and the swoosh of devastating Hurricane Matthew that brutalized Haiti and the Southern U.S. It was North Korea’s brazen nuclear tests; it was the tumbling to earth of EgyptAir Flight 804; it was grisly suicide bombings in Belgium and Lahore, Pakistan; and it was mounting carnage in Aleppo, Syria; Turkey; Nice, France; and Berlin. It was refugees on the run; it was microcephaly-carrying mosquitos in South America; it was extreme summer ice loss at the poles signaling ecological disaster. Dread infused the police standoffs in Charlotte, North Carolina, and the water cannoning of protesters at Standing Rock. And we watched as dread turned to doom on the heels of the worst mass shooting in American history at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub. After a particularly corrosive American election year, it’s hard to still believe in inclusive democracy and not also feel as if the social world itself is under demolition. It’s also important, and surely instructive, for all of us who live in hyperdeveloped nations to come to terms with the fact that our growing sense of impending disaster is the way many people—whether they’re residing in Chad and Cuba or in Palestine or in Bosnia—have long been living.

Naturally, pending calamity spilled into pop: Dylan’s hard rain, memorably covered by a nervous Patti Smith at the Nobel Prize ceremony, seems to have fallen a long time ago, and we’ve really just spent the year doing clean-up in Aisle 2. Everyone’s already noted the stacking body count of iconic boomer-era musicians such as Prince, Sharon Jones, Pauline Oliveros, and Leonard Cohen, but you could feel teeming dread in James Blake’s unredeemably gloomy The Colour in Anything, in Japanese Breakfast’s mournful Psychopomp, in the damaged relationships of Frank Ocean’s solipsistic releases Endless and Blond(e), in the creepy tenseness of Radiohead’s A Moon Shaped Pool, and in Anonhi’s tellingly titled Hopelessness. Bowie courageously chose to confront his own imperiled morality in swan-song Blackstar, and a dressed-down Lady Gaga (who admitted to suffering from PTSD and lingering effects of sexual abuse) mourned the death of her aunt in the acoustic title track from Joanne—the album also included Trayvon Martin–inspired “Angel Down,” with its singularly exposed opening line, “I confess I am lost in the Age of the Social.”

The seemingly unceasing police killings of unarmed black civilians such as Terence Crutcher were met with the profoundly symbolic refusal of quarterback Colin Kaepernick to stand during the U.S. national anthem, but you could also find a related musical defiance in the who-needs-a-record-label, gospel-jubilant wondrousness of Chance the Rapper’s Coloring Book and in rapper-next-door J. Cole’s wisened 4 Your Eyez Only. You could find powerful refusal in Against Me’s acid takedown of the TSA’s trans-unfriendly airport security body-scanners in “ProVision L-3,” a track that inhabits the same universe as Swet Shop Boys’ sharp commentary on airport racial profiling in “T5.” And reunited Native Tonguers A Tribe Called Quest, mourning the cataclysmic loss of member Phife Dawg, brilliantly vomited back up Donald Trump–era distress on urgent “We The People….”: “All you black folks, you must go/ All you Mexicans, you must go /And all you poor folks, you must go/ Muslims and gays, boy, we hate your ways/ so all you bad folks, you must go.” To Ann’s point about nobody listening to each other in our filter-bubble era, it seems that not only is civility out the door, but maybe humanity is hosting its own funeral, too. It may be musicians who can best help bring us back from the dead.

Julianne notes that black women in pop had a productive year: Yup, sistas continued to lead the way by holding forth the optimistic promise of redemption from the trauma of things falling apart. As Carl and Chris note, Beyoncé won the day in Lemonade, especially in the way she offered up therapeutic forgiveness and sorority as solutions after domestic trauma/drama caused by a cheating partner. Jamila Woods’ Heavn and Solange’s A Seat at the Table both illuminated the need for self-care in an exhausting culture of racial microaggressions. Laura Mvula worked through the calamity of a recent divorce in the astounding The Dreaming Room, and Algerian-born Aziza Brahim, raised in refugee camps, soothed with spiritual renewal for the exiled on her gorgeous, pastel Abbar el Hamada. Julianne, thank you for giving props to Dawn Richard: It’s no surprise that her startling 2016 album is called Redemption, given that one of its key songs, “Lazarus,” shares its title with Bowie’s dirge. Both tunes are differing meditations on themes of reincarnation and the afterlife.

Identity politics themselves—wildly uncool in pop not all that long ago—continued their own Lazarus rise from the ashes in 2016. Intersectionality was the year’s overused buzzword—it’s little more than a 21st-century reboot of DuBois’ concept of double consciousness and multiple embodied identities. No surprise that Barry Jenkins’ tender if somewhat problematic film Moonlight, with its focus on the vicissitudes of black gay existence, is the critically praised movie of the year.

Pop music in 2016 showed us that intersectionality, at its progressive best, helps us transcend nihilist-conservative threats that aim to rip the social fabric to shreds. Tattooed ex–boy bander Zayn Malik delivered a brash solo debut that includes “Intermission: Flower,” an R&B prayer sung in mellifluous Urdu (and Zayn is also the title subject of a song on Swet Shop Boys’ Cashmere): We’ve never heard anything exactly like it on a pop album. Full-length projects by Mykki Blanco, Cakes da Killa, and Kaytranada continue to clear space for queer people of color in the pop universe. Intersectionality emerges as a potent political project in Mexican Camilo Lara’s incisive Morrissey/The Smiths tribute band Mexrissey, in the deconstructionist dancehall of Equiknoxx’s Bird Sound Power, and in Saul Williams’ slept-on and rage-filled MartyrLoserKing, which orbits around a fictional story of a Burundi hacker. Intersectionality also powers the softer, politically infused electronics of Chilean American DJ Nicolas Jaar and Senegalese Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri, and you hear it in the danceable cosmo-rhythms of Lisbon’s DJ Marfox and Berlin’s Africaine 808. In 2016, musicians claiming intersectional identities no longer have to leave parts of themselves on the editing room floor in an effort to achieve crossover success—as they often had to in the prestreaming age when physical record sales mattered much more than they do now.

The reactionary pushback in 2016 against undocumented immigrants and refugees of various stripes is part of an ongoing movement to consolidate white supremacy in a moment where demographics are shifting as never before. I’d also like to consider this year’s ratcheted-up anti-woman and anti-trans hostility as an attempt to reconsolidate cis-male supremacy as it too dwindles in power and relevance. The global right turn to reclaiming of power for the already privileged is in some ways a populist rejection of the social and economic changes that globalization, over the past several decades, has wrought: It’s a bristling rejection of the loss and blurring of identity boundaries and borders and a repudiation of the ideal of racial, ethnic, and gender pluralism. The U.S. election, as savvy critics have wisely noted, was in large part about white voters asserting their whiteness, above and beyond other aspects of their identity: One way to sum it up is to consider it a rejection of intersectionality itself. In a year dominated by reactionary white dudes from Trump to Vladimir Putin to Nigel Farage to Steve Bannon to Peter Thiel, now-convicted mass murder Dylann Roof closes out 2016 as the worst of the lot: His is the face of a unrepentant, gun-toting genocidal racist desperately hoping to roll back the social progress of the 20th and 21st centuries.

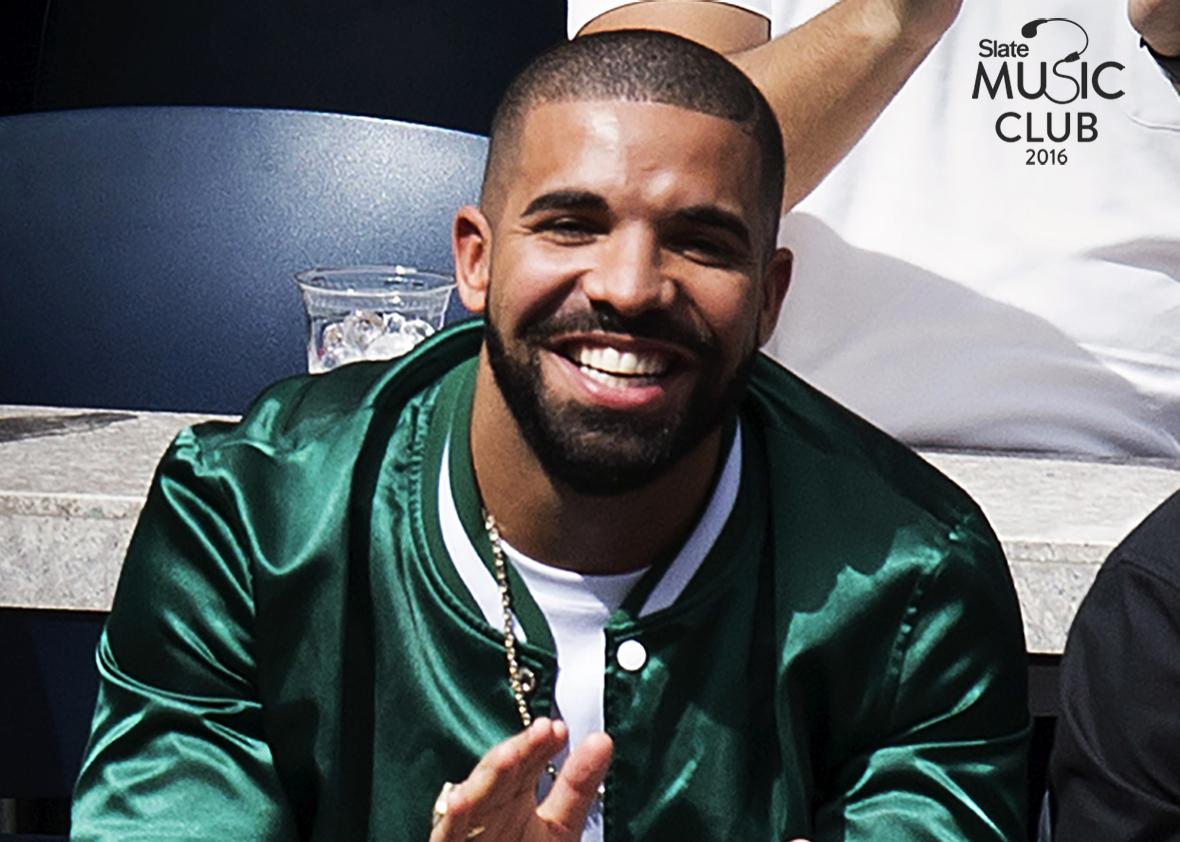

I hope Roof and his ilk do not win the war we’re currently fighting. I love that in a year defined by looming cataclysm, the song of the summer was Drake’s “One Dance.” Besides being sung by biracial Canadian Drizzy and U.K. pop singer Kyla, the track was concocted by Nigerian Afrobeat rapper WizKid and South African afro-house producer DJ Maphorisa alongside Jamaican Canadian producer Nineteen85 of Dvsn and Lebanese Irish Canadian producer Noah “40” Shebib. In some ways, “One Dance” unassumingly flies directly in the face of Roof’s refusal of pluralism and intersectional identity as the future of planetary humanity.

Pop music by itself will never displace the essential work white people need to do to dismantle global white supremacy. It’s never going to displace the work that men like me need to do to dismantle toxic masculinity. It’s no substitute for the work that all of us in developed nations need to do to roll back the toxic effects of hundreds of years of violent, destructive settler colonialism. But what pop music can do is to provide a blueprint for inclusivity and wholeness that can in turn disable the inward-facing retreat to xenophobia and nationalism that imperils us all. Pop, at its best, can represent a building up of possibility to come together rather than a catastrophic demolition and tearing down. That’s why we need it more than ever.

We shall overcome.

“When your heart is broken down, down, down, and your head don’t reach the sky/ Take your broken wings and fly,”

Jason

My Favorite Albums of 2016

1. A Tribe Called Quest, We Got it From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service

2. Africaine 808, Basar

3. Against Me!, Shape Shift with Me

4. Amos Lee, Spirit

5. Aziza Brahim, Abbar el Hamada

6. Baaba Maal, The Traveller

7. Beyoncé, Lemonade

8. Bon Iver, 22, A Million

9. Chance the Rapper, Coloring Book

10. Corinne Bailey Rae, The Heart Speaks in Whispers

11. David Bowie, Blackstar

12. Dawn Richard, Redemption

13. Debo Band, Ere Gobez

14. DJ Marfox, Chapa Quente

15. Dvsn, Sept. 5th

16. Equiknoxx, Bird Sound Power

17. Flume, Skin

18. Frank Ocean, Endless

19. Jacob Collier, In My Room

20. James Blake, The Colour in Anything

21. Jay Daniel, Broken Knowz

22. Joan as Police Woman and Benjamin Lazar Davis, Let It Be You

23. John Legend, Darkness and Light

24. Kanye West, The Life of Pablo

25. Kaytranada, 99.9%

26. Lady Gaga, Joanne

27. Laura Mvula, The Dreaming Room

28. Machinedrum, Human Energy

29. Mexrrissey, No Manchester

30. Motion Graphics, Motion Graphics

31. Nicolas Jaar, Sirens

32. Paul Simon, Stranger to Stranger

33. Radiohead, A Moon Shaped Pool

34. Saul Williams, MartyrLoserKing

35. Swet Shop Boys, Cashmere

36. The Avalanches, Wildflower

37. Tiger & Woods, On the Green Again

38. Tweet, Charlene

39. Yussef Kamaal, Black Focus

40. Zayn, Mind of Mine