Hey you smart people,

The year’s most fascinating development, to me, was the way some artists managed to Trojan Horse drug anthems onto the radio, and into the hearts of mainstream America, by hiding their true meanings under a rug of colossal hooks. These include many of the artists Lindsay touched on: Jidenna’s homage to Nigerian dandy style (and its counterparts to the South, Congo’s Sapeurs) was consciously historical and invoked the new Jim Crow, but it also acted as a bait and switch, using trussed-up outfits to “pull the wool” while his boys “slang ’caine (/cane) like a dandy.” Though for some the video seemed to veer too far into respectability politics, Jidenna and Roman GianArthur’s reedy, even bubbly mien was instructional and rightfully bumped on car woofers at mean-mugging decibels in my neighborhood for the better part of the year.

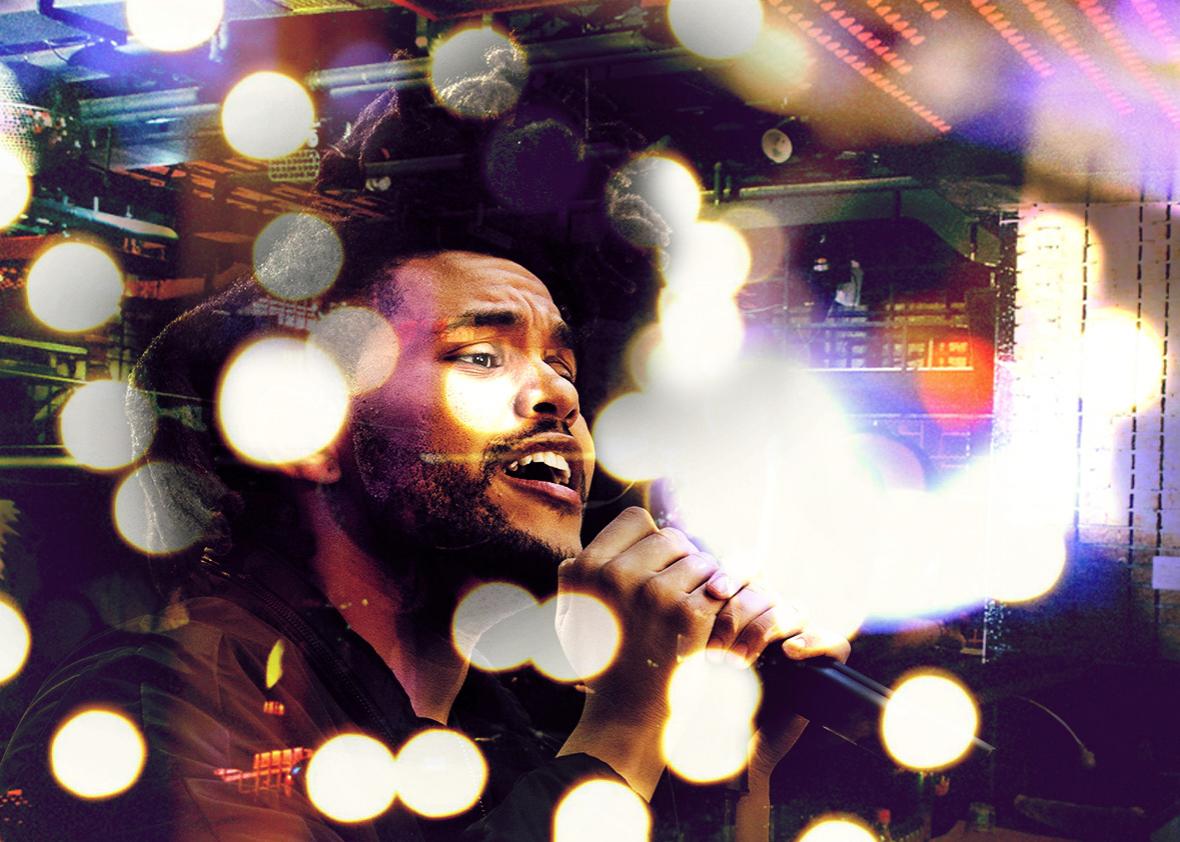

The most brazen drug track was also the biggest, the Weeknd’s “Can’t Feel My Face,” a song piggybacking on a description of cocaine use popularized by Lil Wayne and Juelz Santana in 2008. Abel Tesfaye so insisted he wasn’t singing about yayo that even his girlfriend’s stepdad ended up having to defend it, causing anyone who listened to the Weeknd’s pre–Beauty Behind the Madness mixtape output to roll his or her eyes. But more power to Tesfaye, because his hit single certainly made for more interesting wedding receptions, with aunties and tías jamming out to a track about “white girl” sans compunction. And the success of Fetty Wap’s “Trap Queen” was a small, captivating miracle, its massive popularity holding steady despite its crack-cooking narrative. Disarmingly seductive like just about everything else that’s bad for you, Fetty built on the concept with “Jugg,” enticing a young woman to a life of smash and grabs, crafting a robber’s and trapper’s fantasia into borderline-convincing marriage material. (’Course, he did so with help from his partner Monty, who featured on most of Fetty’s debut. Monty was 2015’s real rap MVP and the most effortlessly romantic man on rap radio, who’ll ask you sincerely how you feel after analogizing your love to that of Gabrielle Union and Dwyane Wade.)

Why is this all happening now? I thought of it all during last weekend’s Democratic debates, in which a talking point amid a refreshingly coherent discourse (comparatively speaking) was the U.S. heroin epidemic, in which deaths have quadrupled since 2002. While it’s disconcerting that opioid addiction had to afflict young white suburban kids to inspire a viable push toward reform, it makes it no less insidious among the demographics that aren’t commanding sympathetic media coverage. Scott Weiland’s recent passing was a terribly sad reminder of how difficult it can be to get clean and how even then addiction can nevertheless haunt a person for decades. Addiction also cast a long, sad shadow over ASAP Rocky’s At. Long. Last. ASAP, which was such a uniquely wavy, psychedelically smart album in part because of the influence of Rocky’s best friend ASAP Yams, who died in January of an accidental overdose at the age of 26.

Yams was a visionary who sought to be the Puff to Rocky’s Mase (another rapper who described himself as “pretty,” in age-old uptown parlance), gifted with all the promise in Harlem World. As the man who formed and then steered the ASAP Mob, Yams seemed to comprehend rap’s future on a vibrational level. His tragic death was a loss for music, and as a gregarious, sweet, and exceptionally funny person, his passing reverberated across New York City and far beyond it, a bright light that everyone agreed should have shined for much longer. Yams’ voice closes out At. Long. Last. ASAP, and on his interlude you can hear his perspective, his fight, his humor. “Y’all just gon’ keep watching us, at the beach show, wit’ ya motherfuckin’ khakis rolled up, wit’ ya chancletas in your hand, and we gon’ keep surfin’ on this motha. Straight up.” His chuckle fans out like a fever dream in a sustained echo effect—wavy forever.

Ty Dolla Sign’s Free TC is haunted by absence, too, named for and peppered by the voice of his brother TC, in prison for a murder for which he insists he is innocent. Craig thankfully noted its brilliance and woeful underpromotion, so with all Lindsay’s talk of sensual men I want to note Airplane Mode, the mixtape Ty dropped a month before his album. Its title track refers to the way Ty likes to keep his iPhone, beleaguered by all the ladies in the inbox. Were the genders and sexual orientations a little different, you could imagine Ty as the object of Drake’s own “Hotline Bling” ire, but the difference here (and with all of Ty’s player’s anthems) is that Ty assumes a semblance of responsibility for his transgressions, his proclivities toward party time making him consciously weary. It shows in his voice, which inherently possesses a bluesy mournfulness—please listen to “Solid” immediately—and occupationally possesses raw cracks from mason jars full of weed, a lifestyle imprint one cannot fabricate. He’s nothing if not explicit, songs like “Sex on Drugs” and “Do Thangs” leaving little to the imagination—but also, because his approach is that of an adult in a landscape of man-boys, refreshingly free of manipulation. “It is what it is” is a pretty workable philosophy when all parties understand the terms from jump. “We could do thangs,” he purrs, but if you do, he already warned you you’re going straight to voice mail post facto.

Still, when these dudes are not as talented as Ty, such free-will debauchery can be tiring. I found a satisfying lightness in Alkali, the debut album from Bronx singer Rahel, which I imagined as an album full of woozy but self-determined response tracks. Her voice is so gossamer to the point of being uplifting, but its ethereal lilt doesn’t mean it’s insubstantial. The video for debut single and quintessential crush song “Serve” confirmed my suspicions that she’s a little bit sardonic; she’s interested in being waited on by the object of her affections and alludes to a lobster date in the song before actually decimating a cooked lobster with a baseball bat in the video. And on “The Break,” over an iridescent set of synth tweets, she levels the chorus: “It ain’t about you, it ain’t about you, it ain’t about you, it ain’t about you.” If I had a mantra this year—from pop dudes’ tiresome narcissism (OK, mainly Drake) to, like, everything else—it was that.

Alkali is also an exceptionally creative album, and it put into perspective how multidisciplinary so many women’s work was this year. Perhaps we didn’t experience a glut of women crafting anthems of unity, but enough solo projects expressed a singular vision that I didn’t need it. Vulnicura wasn’t Bjork’s best album musically, but on a conceptual level it was deeply satisfying to see her further connect the corporeal with the intangible, this time translating her wrenching heartbreak into surround-sound music videos, shot in Icelandic caves, with her pain depicted as roiling lava through her uterus and her broken heart as a vagina. (It was all very second wave.) Dawn Richard’s Blackheart was one of the most rhythmically adventurous releases all year, in R&B or dance or any genre, the second in a conceptual trilogy that she made, mind-bogglingly, during the brief Danity Kane comeback stint. FKA Twigs’ M3LL155X EP was a video installation created with the celebrated artists Matthew Stone and Jihoon Yoo and starred Twigs and begrilled French art patron/muse Michèle Lamy. It arrived after Twigs staged Congregata in Brooklyn and London, a wholly transcendent experience that brought her music and the vagaries of modern dance and performance art to audiences not necessarily acclimated to them. And on the less sanguine end of things, feminist cyborg scholar and soon-to-be Ph.D. Holly Herndon programmed some conceptual computer math into heady techno experiments that were also eminently and majestically danceable; her live performance this summer in Brooklyn was the most transformative show I saw all year outside of the Pinkprint Tour. As a performer, she took topline house and techno tropes and snuck them into her tracks as counterrhythms, filtering her own anti-diva vocals through shifters while two dudes typed jokes to each other on a screen in real time by way of visuals: “DO YOU EVEN LIFT, BRO?” they typed. “LIFTING IS FOR AMATEURS.”

So much more captivated this year—the grime interest in the U.S. for the second time in a decade and JME’s masterful album Integrity; dancehall’s continued obsession with post-Popcaan chill; the success of Fifth Harmony and Little Mix in a recently tough girl-group landscape; Shaquille O’Neal’s transformation into an EDM DJ (after Paris Hilton’s, of course); the meteoric rise of PC Music from SoundCloud nerds to bona fide pop producers; Hamilton, which my friends would like me to shut up about already; and, hopefully, the further emergence of Missy Elliott, of whom Carl’s assessment was on point. But I don’t have another year on my hands to type about all that at the moment. So Jack, I pose to you this question: What were your unforgettable live music experiences in 2015?

Also can’t wait for Zayn’s inevitable trap mixtape,

Julianne

To get each new entry in the 2015 Slate Music Club in your inbox, enter your email address below: